“Reality is not made of statements,” But Stories Are.

In his analysis of paraphrase, Harman argues that “[t]here is no reason to think that any philosophical statement has an inherently closer relationship with reality than its opposite, since reality is not made of statements” (14). Fairy tales make obvious Harman’s warning that metaphysical and ontological realities are not made of or reducible to statements: tellingly removed from the “real” and defined by Stith Thompson as “tale[s] of some length involving a succession of motifs or episodes… [and] mov[ing] in an unreal world without definite locality or definite characters and filled with the marvelous” (8), fairy tales are a subset of the folktale antithetical to nature or reality, to an object as it simply is in a realm of Platonic ideals. In “The Inherent Stupidity of All Content” (11-14), Harman is clearly interested in statements regarding reality (specifically, the relation between Lovecraft’s statements and comprehensible ontological representation), but fairy tales present the exact opposite relation to realism; rather than the typical reception of statements vis à vis the truth, fairy tales make explicit that they do not speak for the world we inhabit. Fairy tales, märchen, or contes des fées are cultural objects whose very names point to the fact that they cannot make any claims to ontological or phenomenological reality, and as such I believe they can be valuable objects to explore Harman’s interest in the politics of experiencing and/or representing an object.

The fairy tale, then, does not attempt to explicate or delineate reality so much as to escape it, and despite being a massive break from Harman’s ontological and literary interest in Lovecraft’s writings, folklore nevertheless exemplifies Harman’s phenomenological gap, most obviously the “horizontal gap,” or what he describes as “the cubist gap between an accessible object and its gratuitous amassing of numerous palpable surfaces” (31). Individual utterances of a specific tale are what define the largely and historically oral tradition of folklore. Each tale’s variant, whether it be that of words or narrative details, becomes the cubist flag flapping in the wind (Harman 30), and his argument that “what we end up with are the truly pivotal qualities of the thing” in Lovecraft’s literary style and phenomenological perspective are exactly the methodologies inherent in folklore studies (31), which typically examines a particular folktale given its various and varying iterations across – and consequent incorporations into – time and space (i.e., its periodization and nationalization, its material distribution via literary and oral renditions in public and private spaces, etc.). In fact, János Honti proposed in 1939 that the fairytale is “a kind of cookie-cutter Platonic form or model which manifested itself through multiple existence [sic]” (qtd. in Dundes 195). This seems remarkably similar to Harman’s example of the flag as an ontological object, where “the specific qualities of the flag encountered at any given moment do not hide the flag as a unitary object, but exist as something extra, encrusted on its surface” and ostensibly expendable in our conception of the object (30; emphasis added). Honti’s notion that a tale-type is a cohesive object with varying manifestations results in the same gap between the accessible object (in this case, the folktale) and its “gratuitous amassing of numerous palpable surfaces” (Harman 30), and moreover informs the classification process of folkloric indexes, which attribute specific iterations of stories to a larger archetypal narrative of the folktale in question. What becomes tautological in Harman’s philosophically inclined argumentation is in fact folklore’s modus operandi. One significant distinction arises: to continue with Harman’s rhetoric, folklorists use each cubist surface or tale’s point of entry for juxtaposition; repetition is not tautological here, but structural, allowing folklorists to recognize specific instances of a larger archetypal tale structure. So while for Harman the “banality” of statements has grave consequences for philosophical theses (14), what his article frames as an issue of discursive relativism (reality is not made of statements) is actually what allows folklorists to identify a tale’s integral constituents, and propose some reality regarding a fairy tale’s identity. In other words, iterations’ variations (within Harman’s argument, a paraphrased statement) reveal an archetypal structure that defines a particular tale and what can be categorized as such a tale, proposing some reality-value regarding a story’s identity rather than revealing, as Harman and Zizek argue paraphrase does, a statement’s removal from reality.

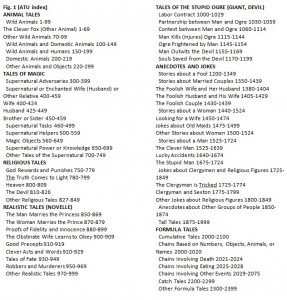

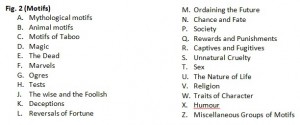

So I began with the premise that the fairy tale genre repudiates reality, and yet have concluded that it still makes a truth claim. In fact, Antti Aarne (1910), Stith Thompson (1928, 1961), and later Hans-Jörg Uther (2004), have created a classification system (herein abbreviated to ATU index, tale type, etc.), which is widely acknowledged as an invaluable source in folklore, “an international sine qua non among bona fide folklorists” and authority on what constitutes a specific tale (Dundes 195). In the ATU index, a folk tale is given a code based on numbers and letters. The number corresponds to types of tales, and the letter to tale motifs (see figs. 1 and 2).

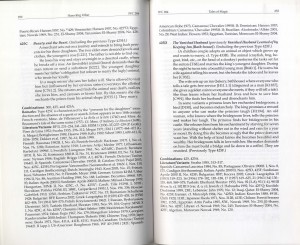

Thus “Beauty and the Beast” is ATU 425C (fig. 3), introducing the motif of taboo (in the particular case of 425C, the Beauty figure “overstays the allotted time” when visiting her family [Uther et. al 252], resulting in the Beast figure’s near demise) to the Search for the Lost Husband tale type. This is distinguished from its mythological predecessor, “Cupid and Psyche,” which is typically identified as straddling 425A (“The Animal as Bridegroom”) and 425 B (“Son of the Witch”). This organization inevitably raises questions: why is “Beauty and the Beast” identified as 425C, whose ATU motif assignment deals with taboo, when “The Animal as Bridegroom” seems to be the larger focus of the tale? When it comes to the ATU index, framing mechanisms emphasize the object as somehow transcendent, yet the mechanism itself is highly mediated.

Perhaps some awareness is necessary of how, as Foucault warns us, “divisions[,]” in this case those between tale types, “are always themselves reflexive categories, principles of classification, normative rules and institutionalized types; they are, in turn, facts of discourse which merit analysis alongside other facts, which certainly have complex relations with them, but do not have intrinsic characteristics that are autonomous and universally recognizable” (303). But the problem can be exceedingly complex, especially when such awareness makes evident just how political categorization can be. For example, is “Cupid and Psyche” 425A, 425B, or should it have its own category? What influences the process of categorization (hint: in the overall category of ATU 425, Search for the Lost Husband, ideologically encoded language and titling which denies female agency and emphasizes patriarchal roles), and what are the limits of these boundaries and their impacts? What does choosing one motif over another as the vital motif imply? If “Beauty and the Beast” is in fact determined by the taboo of Beauty “[breaking] the prohibition of staying home too long” (Thompson et. al 252), the sociopolitical implications of a tale defined by a woman failing to return to the beast who possesses her due to a failed transaction (specifically, her father’s failed transaction with the Beast) is certainly telling. In fact, even the Greenwood Encyclopedia of Folktales and Fairy Tales argues that “[u]nlike the Cupid and Psyche tale… where the emphasis is on the breaking of the taboo that forbids the young woman to look at her husband… ‘Beauty and the Beast’ emphasizes the animal qualities of the groom and his ultimate transformation from a monster into a human being” (106), and yet it is still identified under the “taboo” motif.

Here is where Harman’s “vertical gap” occurs, the one “between unknowable objects and their tangible qualities” (31). A fairy tale is language, words spoken out of mouths or script read on a page. Their tangibility is undeniable, but their categorization, the knowledge of what any specific tale is, remains less certain. Organized by tale type and subcategorized by motif, the ATU index highlights folklore as a medium of repetition, paraphrase and slight transformation. Thus no story will remain identical to its previous iteration, and the very notion of a tale independent from its type confuses and befuddles when considering folklore from within the context of the ATU indexical system. Is “Beauty and the Beast” a distinct tale type, where each iteration or variant is a single unit or cubist facet of its expression, or is it a less certain and more troubling distinction between tales that are, by ATU tale-type definition, different and inherently so? In the instance of ATU classification, a tale’s tangible qualities, a specific variant’s pronunciations, names, regional references, diction, cultural mores, etc. often reveal gaps between what can be known (the tale I have accessed) and the “unknowable object” (Harman 31), or the tale type as a consistent unit or ontological object. However, while I establish a connection between the ATU index and Harman’s ontological “‘vertical’ gap,” it is important to note that Harman’s gap is due to the evasion of signification, whereas the ATU index’s “vertical gap” is due more to an excess of signifiers, of diegetic elements and narrative motifs that expand potential forms of categorization rather than completely evade them. And this is where and how discourse emerges in the ATU indexical system: with an excess of signifiers, discourse becomes the inevitable filter for the database.

Having reached the end of my probe, I realize I have argued that fairy tales are antithetical to reality, make truth-claims regarding a certain kind of reality (regarding the stability of an archetypal tale and the collusive politics of categorizing, naming and consolidating narrative details), and are ultimately undermined by this gesture due to excessive potential signifiers and consequent discursive moderation. And so I, like Lovecraft, find I am unable to directly talk about a thing, and instead must move about it and probe it from different angles while ultimately unable to coalesce these details. Folklore is, like Lovecraft’s writing, “disturbingly alert to the background that eludes the determinacy of every utterance, to the point that [both] invest[…] a great deal of energy in undercutting [their] own statements” (Harman 28). However, I’m comforted by the fact that folklore also struggles with this, and that its rich history of mining tales for traces and motifs that can help identify a story have increasingly battled with the dissatisfaction over motivated categorizations. As Harman argues, “objects are what the classical tradition called substantial forms, inhabiting a mezzanine level of the cosmos, and can be paraphrased neither as a meaning for some observer nor as the dangling product of some genetic-environmental backstory” (253). The ATU index attempts to both identify a “genetic-environmental backstory” (the archetype) as well as provide meaning (“Beauty and the Beast,” according to ATU classification and prioritization, is a story about a woman who fails to return to her husband, as opposed to a story about a woman who becomes an expendable transaction being forced to return to her place of imprisonment). Fairy tales are by definition fiction, but what about their forms of classification? Is an archetype a fact, or a convenient, if not necessary, fiction? Should the methodologies and scholarly paradigms used to study a fairy tale correct their relationship with reality, or emulate what they examine? Is this a matter of preference, or an ethical issue, given the seeming customary (and increasingly moreso) coupling of folklore and ideology? So while Harman argues that “we can only support objects” (253), I would like to emphasize that we must first examine those objects’ relations to us, and in cases like folklore we must also question whether something is (easily) determinable as a cohesive object, and evaluate whether Harman’s phenomenological gaps à la Lovecraft produce valuable complications of just how “we produce our own real objects in the midst of [perception and context]” and the knowledge bases these productions secure (260).

Works Cited

Ashliman, D.L., ed. “Beauty and the Beast: Folktales of Type 425C.” Folktexts: A library of folktales, folklore, fairy tales, and mythology. University of Pittsburgh, 25 June 2009. Web.

Dundes, Alan. “The Motif-Index and the Tale Type Index: A Critique.” Journal of Folklore Research 34.3 (Sep. – Dec. 1997): 195-202.

Foucault, Michel. Aesthetics, Method, and Epistemology. Ed. James D. Faubion. Trans. Robert Hurly et. al. New York: The Press, 1998.

Harman, Graham. Weird Realism: Lovecraft and Philosophy. Washington: Zero Books, 2011.

Swain, Virginia E. “Beauty and the Beast.” The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Folktales and Fairy Tales. Volume 1: A-F. Ed. Donald Haase. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2008 ed.

Thompson, Stith. The Folktale. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1946.

Uther, Hans-Jörg. The types of international folktales: A classification and bibliography, based on the system of Antti Aarne and Stith Thompson. Helsinki: Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia, Academia Scientiarum Fennica, 2004.