Boot Camp: Networks Jerusalem Cook Book

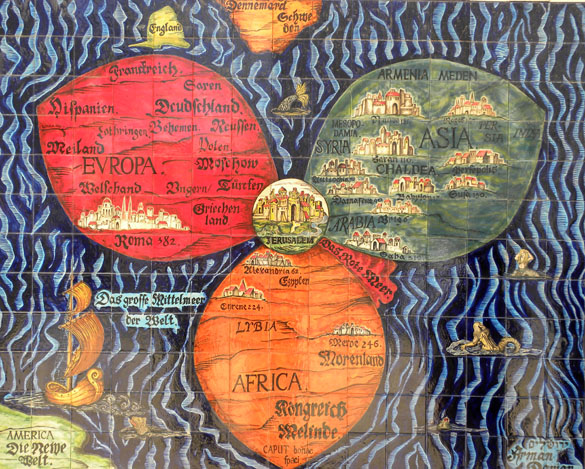

I set out to map Jerusalem’s cultural sectors through the relationships between its culinary ingredients. The thought, absurd as it might seem, was planted in my brain when I came across a famous adaptation of the 1581 Bünting Clover Leaf wood cut. Near Jerusalem’s Municipal complex, in Safra Square, Arman Darian’s tiles position Jerusalem at the meeting point of Africa, Asian and Europe. Despite its “unscientific” representation, the politics of this map are made apparent in its suggested geography. Given its discordant populations and its position as a trading hub, it seemed feasible that ingredients would cluster and, in so doing, point to histories of international trade, colonialism and cultural isolationism.

Arman Darian’s map of Jerusalem in Safra Square

I produced a network diagram of data pulled from Yotam Ottolenghi and Sami Tamimi’s cookbook, Jerusalem. Co-authored by ex-patriots of Jewish and Arab sectors respectively, Ottolenghi and Tamimi’s work has been received with surprising acclaim. The New York Times writes,

“American food lovers are not only cooking from “Jerusalem”; many of them are cooking their way through it, as cooks did with “Mastering the Art of French Cooking” in the 1960s and with “The Silver Palate Cookbook” in the 1980s. “Jerusalem” is the first book in recent memory to join that group, and the first to do it via social media, as well as old-fashioned word of mouth.” (Julia Moskin Jerusalem’ Has All The Right Ingredients)

I strategically chose such an influential work, so that at the very worst I would be offering an interpretation of a culturally salient fiction of Jerusalem’s cuisine.

The software I used is called Gephi. It is an open source data visualization tool. My goal was hopefully simple, create a node for each ingredient and draw an edge between them each time they appeared in the same recipe. I hypothesized that the resulting network would be bifurcated, as Sephardic Jewish recipes gravitated to a set of clustered ingredients on one side, and Arab ones to the other.

My first attempt to manually insert recipes directly into the program produced uninteresting graphs, cluttered by the presence of recipe nodes, rather than connecting ingredients to each other. Appealing to Gephi’s online forums, a user pointed me to their plug-in which allowed me to re-enter data efficiently, effectively allowing me to produce what I imagined possible. It took me several hours of combing for patterns before I admitted I was wrong. Jerusalem’s recipes are not divided cleanly into cultural lineages. Classical North African ingredients such as feuilles de brick and preserved lemons sit next to South Asian spices such as turmeric and cardamom. Underrepresented as they might be, even Ashkenazi (Eastern European) Jewish staples such as matzo meal, are shifted next to basmati rice and the Sephardic spice mix, ras el hanout.

Ottolenghi and Tamimi predict my results in their introduction, explaining, “in this soup of a city it is completely impossible to find out who invented this delicacy and who brought that one with them. The food cultures are mashed and fused together in a way that is impossible to unravel. They interact all the time and influence one another constantly, so nothing is pure anymore” (Ottolenghi & Tamimi 2012).