Boot Camp – Network Diagram Image – New Tools for Old Texts – Making it New?

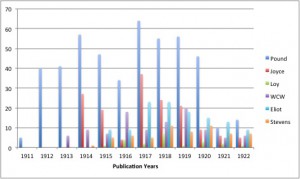

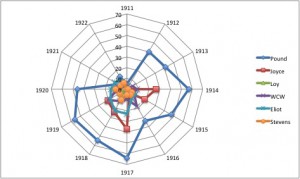

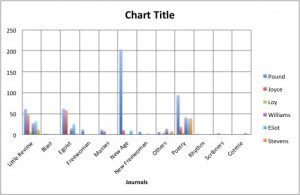

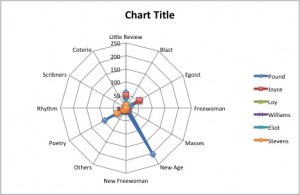

The initial challenge encountered in approaching this boot camp involved the difficulty in deciding upon a subject. How could the quantitative methodology involved in producing a network diagram reveal a specific insight to an area of my interest and study? My initial conclusion was that should I be able to determine exactly how many times Joyce or Pound directly reference the Pauline Epistles in their writings, and where in their writings such reference were made, I would, indeed, have found a viable and vital method of inquiry. But, of course, this is what I am already attempting to do. My methodology, however, is the painstakingly slow process of close reading. I read and reread the texts involved discovering the relations and attempting to determine how those relations impact the development of the theological, philosophical, political and sociological dimensions of the primary texts involved and how that subsequently reflects the particular aspects of the Modernist agenda within the specificity of the reception and developed interpretations of Paul. But where would I begin to acquire the necessary data that could be utilized in the formation of a pictorial representation of such a project? I came to realize that I had to temper my ambition to suit my limited “digital” knowledge – I am not tech savvy and am very much situated in the idea of the text as the end all and be all object. So, I spent some hours surfing the net looking for sites that have focused on Paul and Joyce and Pound hoping to find some kind of data retrieval program that would assist me. What I concluded was that while there were sites that yielded much data, there was little that seemed to make the connections that I was seeking. I decided that my approach, again, needed to be modified. Relegating Paul to the back burner, I focused on Pound and Joyce looking for an approach that would relate to their early development (which is also the early development of the “high” modernist period I am interested in). With Moretti in mind I went looking for a subject that involved the “connections within large groups of objects” (Moretti 212) that corresponded to Joyce and Pound and that had been embraced by the digital world in such a way that I could retrieve enough data (without having to read through countless pages of text) to produce a diagram that would reveal some existing pattern relatable to the early development of their production. Thankfully, I came across The Modernists Journal Project (http://www.modjourn.org/): a searchable databank correlating early modernist journals with the writers and artists associated with them. Included in this databank were the more known journals such as the Little Review, Poetry and The Egoist as well as more obscure journals such as Rhythm, Coterie and Freewoman. Where would Joyce and Pound be situated in terms of the number of publications within these journals in relation to other known modernist writers of the period? Setting my parameters to cover the years between 1911-1922 and limiting my inquiry to twelve journals and four writers other that Pound and Joyce (Mina Loy, William Carlos Williams, T.S. Eliot and Wallace Stevens) I proceeded to explore the possibilities within the web site.

The results were of interest: Pound’s dominance regarding publication and influence was pronounced (as was to be expected). But the distribution of relevant publications by Pound and the other writers and how these published poems and essays were circulated among the different journals at different times suggests the need for further investigation and inquiry. Pound is the only one to publish in Freewoman – T.S. Eliot the only one in Coterie – and the journal Others is the most prominently represented journal of the lesser known outlets for the early modernists (with William Carlos Williams having more than double the number of writings there than Pound). What explains the higher activity of 1917? Why the disproportionate number of search “hits” for Pound in New Age? Looking at these graphs encourages these questions and many more that, while they may have already been explored to some degree, inform a relational pattern that is situated during a peak period of experimentation and the advent of an avant-garde that created it’s own distribution avenues in order to disseminate their particular views regarding the modernist moment (a comparison with the multiple avant-garde journals of Europe that were developed at the same time and any cross-over affiliations would be most interesting). There is clearly much more that can be done with this approach and with this web site tool – the circulation of the Poundian influence alone could be mapped through a more detailed and comprehensive accumulation of data. The numbers, once plotted into a diagram become less obscure and reveal patterns, clusters and networks that open areas of new possibility. Having now engaged in this procedure myself I can more clearly comprehend Moretti’s argument, though I align myself with James Murphy who takes a pragmatic view of Moretti’s work:

but I have continued to feel the rush of reading Moretti for the past decade and a half or so in part because he’s so persistently reminded us that we literary critics do indeed actually have data and we need to learn how to dig into it. Literary scholars are sometimes reluctant to acknowledge this fact because our métier is placing words like “data” and “facts” into question; we are awfully good at problematizing, but sometimes problematizing can be a problem in itself (Murphy, http://magmods.wordpress.com/2011/08/18/how-to-do-things-with-networks-a-response-to-franco-moretti/)

A couple of final notes: I am very disappointed with the graphs that I have posted. The 2-3 hours (at least) spent trying to gain a working knowledge of Excel produced sub-par results and speak directly to my limitations when it comes to utilizing the tools at my disposal (and I believe I am far from alone in this situation). Furthermore, I spent twice that amount of time attempting to transfer my data into the Gelphi program which finally defeated me when a recurring “java script” message suddenly and relentlessly kept intruding just as I had finally started giving shape to what would have been a much more informative diagram. The ensuing frustration has convinced me that my lack of computer and digital knowledge is unacceptable, and that in order for me to fully take advantage of the research tools at my disposal, I must rectify this weakness. This is not to say that close reading and hermeneutic approaches to research are any less important than they have always been. The digital tools (and theories) augment the established methodologies and together can yield much in terms of information and knowledge. The “computational analysis” of literature is with us and will undoubtedly become more and more relevant. The place of theory is still, at times, confronting resistance but the tools and the “networks” are helpful and necessary beyond measure. To Moretti, again:

what I took from network theory was its basic form of visualization: the idea that the temporal flow of a dramatic plot can be turned into a set of two-dimensional signs – vertices (or nodes) and edges – that can be grasped at a single glance. ‘We construct, and construct, and yet, intuition remains a good thing’, Klee once wrote, and that’s exactly how I proceed here, (mis-) using network theory to bring some order into literary evidence, but leaving my analysis free to follow any course that happened to suggest itself. (Moretti 211 italics in text).

Works Cites:

Moretti, Franco. Distant Reading. Verso: London, 2013. Print

Murphy, James. “How to do Things with Networks: A Response to Franco Moretti.” Magazine Modernisms, 18 August 2011. Web. 11 November 2013