Boot Camp – Fucking Up with Brer Rabbit

To fuck something up – to deform – deformation. There is an immediate resistance to this prospect. Fuck up, deform, deformation – these words are instilled with a negative connotation – at least in so far as we are applying them to an object that we either admire or respect. Exploring the formal qualities or interpretative possibilities of a work of art is integral to the scholarly enterprise. The performance, the creation is the domain of the artist. Our lot is to sift through the final product (object) – observing, exploring and extracting possibilities of “meaning” through the application of absorbed methods of formal critical analysis (historical, psychological, etc.) and theoretical propositions that problematize and elucidate the functionality and relevancy of the chosen scholarly artistic systems. The goal is NOT to fuck it up (or to fuck up) but to contribute to the overarching influence or impact of the object/subject within the social, political and historical continuity of our developing culture. A conduit reaching across a social stratosphere, engaging a brotherhood/sisterhood of not necessarily like-minded fellow scholars, but scholars nonetheless who share a common language and theoretical foundation from which coherent analysis and regulated conclusions can be drawn, disputed, challenged and re-developed so as to allow for an intelligent discourse to grow and adapt to new critical propositions and methods in the pursuit of “understanding” and appreciation. Let the artists fuck it up and we’ll come in and put “Humpty” together again discovering new insights and culturally significant revelations (apocalypses?) along the way. Let Jackson Mac Low pilfer and “deform” Pound’s Cantos – we’ll expose the significance and debate the silence at the end. After all, we are the ones who have been in training for years – not to “create” but to explicate.

Or so I was led to believe.

But we fuck things up all the time – and we create. We develop the discourses that lead to propositional analyses that manifest into creative/created objects (articles/books) that become the subject of further critical and hermeneutic dissection. Hugh Kenner is as legitimate a target of scholarly research, as is James Joyce (think of The Pound Era). And we fuck up through our misreading and our ability to decontextualize and impose “meaning” through subjective politicalized agendas conforming to the critical flavor du jour. Scholarly research is a messy business and is sustained only via the whims of the “committee”. Cater to their focus, and the money flows. Piss them off (fuck up?) and you better have a trust fund if you want to stay in business. So we search for new avenues of excavation by which we can justify our status – and why not – what we do is a performance – a dance within the realm of the critical, a dance with clashing and transformative networks and discourses that cultivate a plethora of achievable potentiality. So let’s find innovative ways to fuck up, to perform and to create new archeological paradigms by which we can explore the evolving objects of our interest.

Man was first a hunter, and an artist: his early vestiges tell us that alone. But he must always have dreamed, and recognized and guessed and supposed, all the skills of the imagination. Language itself is a continuously imaginative act. Rational discourse outside our familiar territory of Greek logic sounds to our ears like the wildest imagination. The Dogon, a people of West Africa, will tell you that a white fox named Ogo frequently weaves himself a hat of string bean hulls, puts it on his impudent head, and dances in the okra to insult and infuriate God Almighty, and that there’s nothing we can do about it except abide him in faith and patience.

This is not folklore, or quaint custom, but as serious a matter to the Dogon as a filling station to us Americans. The imagination; that is, the way we shape and use the world, indeed the way we see the world, has geographical boundaries like islands, continents, and countries. These boundaries can be crossed. That Dogon fox and his impudent dance came to live with us, but in a different body, and to serve a different mode of the imagination. We call him Brer Rabbit. (Davenport, 3-4 Italics added)

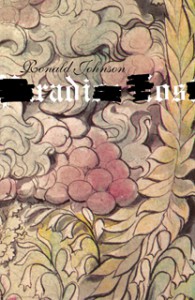

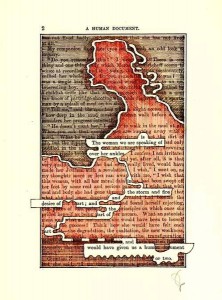

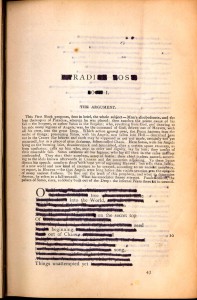

McGann and Samuels insist that their approach “does not stand opposed to interpretive procedures as such […] [it] moves to break beyond conceptual analysis into the kinds of knowledge involved in performative operations – a practice of everyday imaginative life ” (McGann&Samuels italics added). The “deformative critical operation” according to their paradigm encourages an exploration of “unvisited precincts of imaginative works” (McGann&Samuels 36). But, as Sample points out, once these unvisited spaces are revealed, the process resituates the original text within its hierarchical position and the orthodoxy of foundational critical inquiry is re-established “But however much deformance sounds like a progressive interpretative strategy, it actually reinscribes more conventional acts of interpretation” (Sample). This would appear to be a necessity if the critic maintains an institutional parameter whereby there is a precise object of focus (the poem). To not return to the original would be to engage in the “poetic” creative imagining of a new entity. The critic is no longer an expositor but is transformed into an artist engaging in the same creative gesture as Ronald Johnson or Jackson Mac Low (Radi Os and Words nd Ends from Ez, while necessarily creative critical commentaries on Paradise Lost and The Cantos respectively, are poems in their own right and are generally viewed as such within the academy).

from

Words nd Ends from Ez

by

Jackson Mac Low

________________________________________

Words nd Ends from Ez

I. From Cantos I-XXX

1/9/81 (EZRA POUND)

En nZe eaRing ory Arms,

Pallor pOn laUghtered laiN oureD Ent,

aZure teR,

un-

tAwny Pping cOme d oUt r wiNg-

joints,

preaD Et aZzle.

spRing-

water,

ool A P.”

cOnvict laUghter scaNy)

me, MaD E aZure TyRo,

of wAve-

cords,

If I rearrange the order of Eliot’s Waste Land (a form of reading backward) – begin with “Shantih, shantih, shantih” (The Peace which passeth understanding, the Peace which passeth understanding, the Peace which passeth understanding) and then “April is the cruellest month ….”, my deformative act has constructed a new object that can then be assessed as such (the immediacy of the foreign leading into the “normative” oxymoronic designation of spring as a negative condition suggesting that it is an alien assessment proposing an inversion affirming that April is, in fact, not cruel – or numerous other possible “interpretations”). Or if I replace the word Usura with “interest” in Pound’s Canto XLV – altering – will it now reveal, confirm or suggest an underlying potentially auspicious reading – upsetting the particulars regarding the (de)generative means and ways of production in relation to the distribution of wealth while removing the biblical nuances associated with usury? The point being that at this stage the poem, in its deformed state (and, of course the deforming rearranging could be much more involved) is susceptible to associative liminal approaches that could be isolated within the context of the new construct OR reconstituted into the original order of the text and assessed accordingly. Either way, does this deformation involve a “fucking up”? If this procedure constitutes a “[tearing] apart [of] existing structures and [using] the scraps” (Sample) then, perhaps, the original has been fucked up (though what we mean by “fucked up” is an interpretative issue) – though the results could still yield positive results within a broader cultural context. But, if the McGann/Samuels paradigm is maintained, then the original will be always present and the deformity is only a temporary measure by which new exploratory options have been revealed – a new imaginative act that opens windows into hidden spaces or “forms of discursive order which exceed conceptual formulation” (McGann and Samuels 37) – hardly a negative or “fucked up” endeavor. What can be said about academic archeology, however, is that the “boundaries” of imagination (in the geographical Davenportian sense) can more easily be crossed/ruptured and rearranged revealing that “Ogo” is very much at home and in sync with his trickster (deformative inducing) cousin Brer Rabbit – the innate, unavoidable application of the imagination in any scholarly practice shades all ensuing discourses – disrupting, deforming (fucking up?) and, ultimately revealing “possibilities of meaning” (McGann and Samuels 28) through performative gesturing.

Works cited:

Davenport, Guy. The Geography of the Imagination: Forty Essays by Guy Davenport. Boston: David R. Godine, Publisher, 1997. Print.

Eliot, T.S. The Complete Poems and Plays of T.S. Eliot. London: Faber and Faber Limited, 1969. Print.

Johnson, Ronald. Radi os. Chicago: Flood Editions, 2005. Print.

Mac Low, Jackson. Thing of beauty: New and Selected Works. Berkeley: University of California Press. 2009. Print.

Pound, Ezra. The Cantos of Ezra Pound. New York: New Directions Books, 1993. Print.

Sample, Mark. “Notes Towards A Deformed Humanities” SAMPLE REALITY. N.p., n.d. Web. 15 Nov. 2013.<http://www.samplereality.com/2012/05/02/notes-towards-a-deformed-humanities/> .

Samuels, Lisa, and Jerome McGann. “Deformance and Interpretation.” New Literary History 30.1 (1999): 25–56. Print.