Reading series/reading sound: a phonotextual analysis of the SpokenWeb digital archive (Al Flamenco, Aurelio Meza, Lee Hannigan)

The Reading Series

In the past twenty or so years, a large number of poetry sound recordings have been collected and stored in online databases hosted by university institutions. The SpokenWeb digital archive is one such collection. Housed at Concordia University, SpokenWeb features over 89 sound recordings from a poetry reading series that took place at Sir George Williams University (now Concordia) between 1966 and 1974. In the early 2000s, the original reel-to-reel tapes were converted to mp3, and by 2010 the SpokenWeb project, using the SGWU Poetry Series as a case study, was well into its exploration for ways to engage with poetry’s sound recordings as an object of literary analysis.

The collection’s ‘invisibility’ prior to its digitization (for over twenty years the original reel-to-reel tapes remained undiscovered, unreachable, forgotten, or deemed unimportant) is a glaring reminder of printed text’s monopoly in literary analysis and cultural production. Certainly, the written manuscripts of some of North America’s most important twentieth-century poets would not have collected dust for so many years, as did this collection of aural manuscripts — a collection which, as Murray and Wiercinski observe, “[draws] attention to the importance of sounded poetry for increased, complementary or even new critical engagement with poems, and . . . [disrupts] the marginalization of poetry recordings as a subject for serious literary research” (2012). However, before the SpokenWeb recordings became available in an online environment — before they became objects — they were an aggregate of inert documentary data — that is, a collection of archived materials (recordings, posters, newspaper write-ups) that together formed a unit of cultural production (reading series), shaped by bodies (organizers, audiences, poets), spaces (locales), and institutions (scholarly, poetic). Indeed, in order for a reading series to become a coherent object of literary study, its traces, what Camlot and Wershler call “documentary residue” (6), must be properly considered, for they are the constituents of meaning-making through which hermeneutic analyses of recorded audio filter. In other words, the SpokenWeb collection “urge[d] us to consider [the sound archive] as a result of social and technical processes, rather than outside them somehow” (Sterne 826).

As a coherent (if partial) unit of study, SpokenWeb, or the recorded reading series in general, allows us to return (if artificially) to an ephemeral live event, see beyond the archived document, and interpret it as an aggregate, one that is historically, technologically, and culturally specific. But how do we approach this aggregate? What might this particular phonotextual anthology tell us about modes of literary production in Canada in the late 60s and early 70s? How do we begin unpacking this data set? What does it mean to distant listen, or how do we read sound?

We began with an assumption, drawn from a recording of Robert Duncan’s 1965 lecture at the University of British Columbia, in which he speaks for over two hours, lecturing about poetry and poetics and reserving very little time for the reading of poetry in general, which seemed to oppose his claim of being a derivative poet.

Duncan, whose derivative poetic philosophy can be understood as a reincarnation of Romantic concepts of self-disintegration, highlights the inherently paradoxical nature of so many mid-20th century poetry readings — that is, existential consolidation of the poetic self through expository articulations of self-effacement. Which is to say, Duncan renounces the lyric “I” but uses a significant portion of his readings to talk about himself, a trend that proved true in his 1969 Poetry Series reading. This we determined by using the timestamps on Duncan’s recording to create a ratio between poems and extra-poetic speech. By extra-poetic speech we mean the content in the space between poems, where Duncan actually lectures about his poetry, provides anecdotes, or comments on his performance. Excluding George Bowering’s introduction, Duncan reads for two hours, six minutes and fifty-six seconds (another long session, by standard). For one hour and twenty-two minutes, he reads poetry. The remaining fifty-two minutes are filled with extra-poetic speech.

The balancing of poetry and poetics in Duncan’s reading led us to consider how other poets in the reading series might have organized their performance, and what that organization might reveal. For Duncan, it illustrated how aural performance can complicate poetic praxis. How do other poets organize their readings? Are there patterns to suggest that particular schools of poetry favour a certain structure of performance? Do poets begin readings with shorter poems, to ‘warm up’ their audience, and read longer poems in the middle? Do men read differently than women? Is there a relationship between venue and performance? Date? Time? Audience? The SGWU Poetry Series spanned nine years — would there be any recognizable changes in these patterns over that period? It became evident that the aggregation of reading series data could potentially reveal the social, historical, and cultural contexts that shaped the reading series, and also the underlying ideological structures within which the series took place. However, this information is difficult to access because the tools through which we attempt to do so are opaque (temporally, medially) and biased (i.e.who gets recorded, when, where and why). The reading series’ transcripts, it turned out, were a rich tool. But it wasn’t the shiniest.

Findings in the SpokenWeb archive

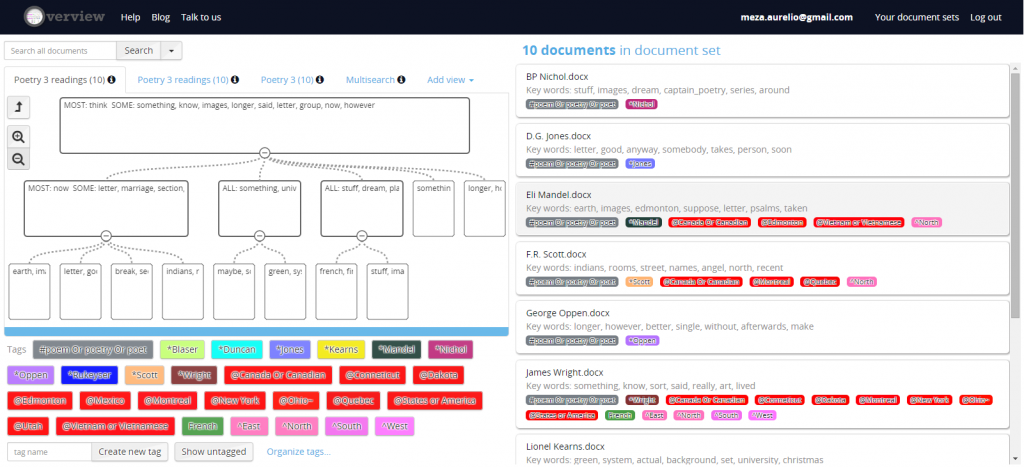

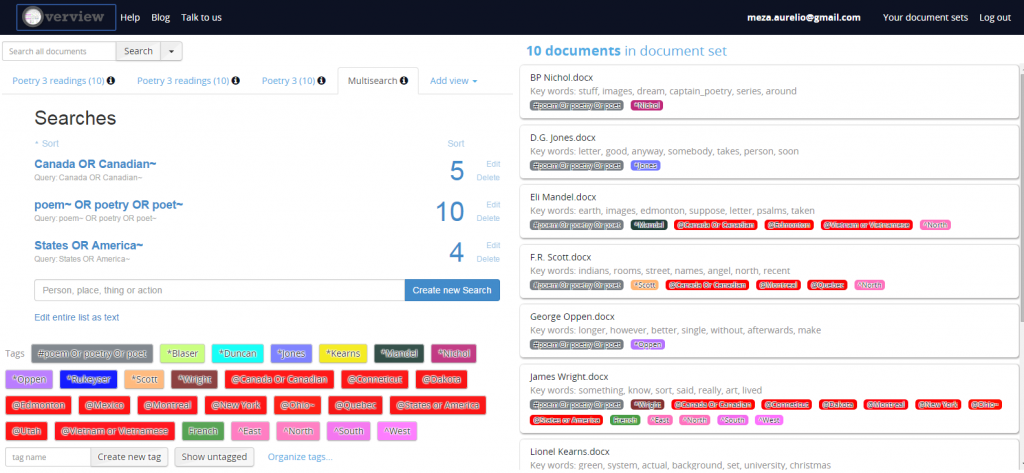

Fresh from Antonia and Corina’s workshop, we were excited to experiment with Overview, hoping to draw some quantitative results from the reading series transcripts. The possibility to tag, classify, and organize documents, as well as some of its visualisation tools, allowed us to access the documents in a different way, which went back and forth from a distant read to a close one. More than a visualisation program, Overview is an archive-classifying application; it helps to sort out big numbers of documents. In our case, it was not possible to aggregate all the readings made throughout the seven series, which would account for 65 poets. But we used the transcripts for the first three series and tagged the locations we found in them, in order to find if there were any recurrent mentions. Apart from topic classification, other functions of tagging include author/genre identification and reviewing control.

With our collections of extra poetic speech from the first three poetry transcripts of the SGWU Poetry Series, we began our tests with Overview with a specific question in mind: What can the extra-poetic speech, this “documentary residue,” tell us about the poets in this reading series, as well as their literary work? The “distant listening” approach we followed here to analyze the SpokenWeb archive suggests that these new forms of mediation have a strong influence on the way we consume, read, or listen to literary/cultural objects. Distant listening shifts meanings within the analytical process, and forces us to reconsider what is deemed important in a critical endeavor.

The fact that we were not able to analyse the poems read at every series (with few exceptions) guided our research to focus on extra-poetic speech. It is true that not all poets would explain in detail the content, form, or other aspects from their own work, but most of them would find it necessary to say a few words about it — and in some cases, such as Duncan’s, it would take a considerable amount of the reading time.

Although our approach was presumably distanced from the reading series as individual audio files, many initial assumptions were grounded in a close reading/listening approach. However, the fact that we could actually find patterns and correspondences among different readings helped us to identify whether these assumptions could be “quantitatively” confirmed. The use of tags on Overview to identify the mention of geographical data (places, locations, directions) provides significant information about how some poets perform their work in public, as well as it reveals some of the biases implicit in the reading series, which can probably be grasped by quickly skimming through the names of the invited poets, but which are confronted and confirmed through the tagging process.

One of these initial assumptions was that there was an evident slant toward North American/European authors, and therefore toward what Walter Mignolo, following Ella Shohat, would call their “enunciation loci”– the discursive “places” from which they talk about (2005). Nevertheless, can this assumption be proved through the methodological tools offered by Overview? Let’s have a look at the geographical mentions in the Poetry 3 readings, held throughout the 1968-1969 academic year.

Out of the ten poets who read in Poetry 3 (George Oppen, B.P. Nichol, Lionel Kearns, James Wright, Muriel Rukeyser, F.R. Scott, Eli Mandel, D.G. Jones, Robin Blaser, and Robert Duncan), most of them mentioned at least one city, country, or nationality. Although all of the poets were Canadian or American, only five of them mentioned “Canada” or “Canadian” (two Canadians — Mandel and Scott — and three Americans — Wright, Rukeyser, and Duncan). With the exception of Rukeyser, most of them also mentioned Canadian cities, such as Edmonton (Mandel), Montreal (Scott, Wright, and Duncan) or Quebec City (Scott, who was born there). It is significant to note that the three poets who mentioned “America”/“United States” are the same who mentioned “Canada”/“Canadian” (Wright, Rukeyser, and Duncan), so we might say that geographical location is more important for these poets than others in the series. Particularly in the case of Wright, he uses location in order to contextualize his work. Not only is he the one with more geographical references in Poetry 3 (he mentions Canada/Canadian, Connecticut, North and South Dakota, Montreal, New York, Ohio, and America/United States), but also the only one who uses the coordinates East/West to talk about different regions in the US.

What about non-English speaking locations? It is revealing to notice that only one poet (Scott) talks about Quebec, and not to refer to the province but rather to the city. In the light of the social events going on at that time, out of which the Quiet Revolution is the most remarkable, Scott’s solitary mention is actually revealing about the tensions and silences around social and political shifts in the region. Another major political event at that time was the Vietnam War, and only Duncan addresses it when he presents his poem “Soldiers.” In the case of Latin American countries, there is only one mention to Mexico (by Rukeyser, who like Samuel Beckett translated Octavio Paz into English) and one mention to Cuba and the Dominican Republic (Lionel Kearns).

These findings are provisional, as the whole SpokenWeb database has not been processed enough to reach to some general conclusions, but from preliminary analyses as the one above we can assume that most of the works performed in the Poetry 3 series were predominantly focused on North American places and (presumably) topics. Even the mentions to places outside North America, like Cuba or Vietnam, are connected to their relation with the United States.

Methods, Implications, Returns

Although we utilized overview as a tool that could enable ‘distant listening,’ our use of the software inevitably generated a typical close listening of the extra poetic speech that we derived from SpokenWeb. Our data sets from Poetry One, Two, and Three provided useful substance from which we could anticipate certain conclusions on topics such as poetic philosophy, performance tendencies, and topic content. Once we filtered our data through Overview’s algorithm, we began to question how this tool generated a novel set of information that we could not otherwise obtain from using keyword and word number searches in a standard word processor. Initially, it seemed to us that using software such as Overview would enhance our analysis of the material in a manner that would help us depart from a close read. However, we essentially returned to a typical literary approach to our extra poetic speech content through Overview. We had to reconsider our analytic stance towards this dataset, and to identify how exactly our examination would lead towards an effective distant listen of SpokenWeb. Ultimately, extra poetic speech does not qualify as literary text; first and foremost it is the speech sounds that precedes, interjects in, and concludes a given poetry reading. Extra poetic speech is inherently ephemeral – for unrecorded performances – given that it is spoken within the parameters of a reading environment and is not necessarily scripted in a physical document. However, with SpokenWeb, extra poetic speech is very much privileged as substantial and informative data in the form of audio recordings and transcripts. Naturally, a close reading of a transcript felt like the most organic analytic approach; yet, when we considered the forum — date, time, location — in which these poets delivered their readings and the significance of extra poetic speech, we began to reflect upon methods of cultural production and the tools that facilitated the Poetry Series’ preservation.

Phonotextual artifacts (collected in a database) provides invaluable material that enables us to consider things such as:

1) The physical bodies present during the reading

2) The physical space in which the reading occurred

3) Reading order among poets

4) Funding Methods

5) Performance styles

We have this dataset from the Poetry Series since individuals involved with its production recorded the readings on reel-to-reel analog tapes. Decades later, the formation of the SpokenWeb database created the necessary digital environment in which we can analyze and deconstruct MP3 sound recordings and written transcriptions that otherwise would have been lost given the readings’ ephemeral nature as spoken performances. This organized, catalogued, and coherent dataset produces a critical environment in which we can examine how these tools (reel-to-reel/MP3/database/transcripts) produce culture by re-creating the Poetry Series through contemporary technological constraints.

In this context, printed text does not hold its monopoly as the primary object in the fields of literary analysis and cultural production. Audio recording – and its component parts in the form of transcript and database – is one possible source from which we can mine digital data and derive meaning, creating new avenues to identify untraditional sources as the subject of literary analysis. However, we could not escape our methodological tendencies by applying a traditional close read. This phonotextual material perhaps necessitates a new methodology from which we can apply an appropriate analysis, or maybe it requires a blend of both close and distant (which we ended up performing). Regardless, the process remains opaque primarily because we were uncertain exactly what it meant to distant listen and read sound. We managed to derive some qualitative conclusions based on a set of quantitative data, but the most striking conclusion resulted from what we could perceive to be the relationship and evolution between forms of cultural production.

The SGWU Reading series recorded on reel-to-reel tapes represents a form of material cultural production. The reels themselves remained limited to a very small audience – perhaps even a non-existent audience prior to its rediscovery and digitization. Its conversion into MP3 entirely expands its material limitations given that it is widely disseminated across a broad audience with features that digitization and database cataloguing privilege. What began as a perfectly useless database (what Camlot described) now enables such endeavors as our specific experiment and the potential for others to perform countless other inquiries. As a form of cultural production, this multifaceted reading series (in its several manifestations) represents how our academic field broadens when expanded beyond print.

Works Cited

Camlot, Jason. “SGW Poetry Reading Series.” SpokenWeb. n.p. n.d. Web. 11 Nov. 2014.

—. “Sound Archives.” Beyond the Text: Literary Archives in the 21st Century Conference. Yale University. Beinecke Library, New Haven, CT. April 2013. Panel discussion. MP3.

Duncan, Robert. “Reading at the University of British Columbia, August 5, 1963.” PennSound. n.p. n.d. Web. 11 Nov. 2014.

Mignolo, Walter. “La razón post-colonial: herencias coloniales y teorías postcoloniales.” Adversus 2.4 (2005). Web. Nov. 2014.

Murray, Annie, and Jared Wiercinski. “Looking at Archival Sound: Enhancing the Listening Experience in a Spoken Word Archive.” First Monday 17.4 (2012): Web. 20 Oct. 2014.

“Overview Project Blog – Visualize Your Documents.” Overview. n.p. n.d. Web. 11 Nov. 2014.

Sterne, Joanthan. “MP3 as Cultural Artifact.” New Media & Society 8.5 (2008): 825-42.