Articulate Air: Channel 4, Stuart Hall, and the Black Audio Film Collective

Etymological Preamble

“Articulation” is rooted in discourses of both law and the body. Derived from the Latin articulus, meaning “small connecting part,” the word referred to the location at which joints or ligaments connect, and is still employed in our current use of “articular surfaces” in the language of anatomy. But ironically, “to join together” also presupposes a separation, because one cannot join that which is already same. To join is also to separate into joints. This is why we retain the sense of “uttering distinctly” and apply it to pronunciation and elocution. In the late 16th-century, perhaps retaining the Roman spirit of legality, articulation meant “to set forth in articles,” or to lay out the clauses of a statute or contract. While this sense has largely fallen out of use, articulate maintains an affinity with its sister word article. Today we often use it to mean expressing or formulating an idea well, or the proper adherence of performance to intent. Here there may be something of a betrayal of the spirit of the word, because in language “expression” alone lacks meaning without a connecting part, that is to say, communicative exchange.

Postmodernism or What

As if it isn’t enough that postmodernism is a term that is often talked about but little understood, the very fact that it is often talked about and little understood is interpreted as a symptom and taken up as a point of access into its meaning.

As the story goes, the modern era emerges out of Europe sometime in the late nineteenth century. With it a sense of unity and wholeness in the world becomes impossible, and people long for it back. Then, in the 1960s, the postmoderns come out and say that this story is a fabrication and that unity and wholeness is overrated anyway. They say they want to hear another story, and another.

“Postmodernism” has been applied to both specific techniques and broad assemblages; from a shorthand for self-reflexive and metafictional experiments in (mostly American) cinema and fiction during the 1960s and 70s, to sweeping accounts of “the cultural logic of late capitalism.”

It has also been characterized as an effect wrought on the generation of readers who grew up reading criticism and literature that theorized modernism, rather than exemplified it.

Today it has become fashionable to posit postmodernism’s end and stake a claim in postpostmodernism, but perhaps now we are even post that. Wherever one stands, it is perhaps with irony that one recalls how an aesthetic movement’s self-conscious rejection of the past and the evocation of the new is a defining hallmark of modernity (yes, that one).

Hall’s Objection

In an interview with Lawrence Grossberg, Stuart Hall gives an account of the way the modernism undermines realism, rationalism, and representational form, but he doesn’t think of postmodernism as something radically and fundamentally different. Instead, he sees it as quantitative change, an exaggeration or extension of modernism updated for new experiences, instead of something qualitative. “The attempt to gather all [the new things postmodernists point to] under a singular sign—which suggests some rupture or break with the modern era—is the point at which the operation of postmodernism becomes ideological in a very specific way,” Hall insists, meaning postmodernism may locate tendencies, but the location of postmodernism itself is only ever an imaginary relation (47). So while contemporary culture’s appeal to historical identity is indeed radically de-centered and fragile, this is a deepening of the same skeptical wound formed in the modern era. Before we hear the claim that ‘we have never been modern,’ we can imagine Hall saying, ‘we are not yet postmodern.’

What results is something of a balancing act between finding ways for meaning and signification to exist while at the same time recognizing their instability. Among Hall’s overview of postmodernist theorists, his critique of Baudrillard exemplifies this best. He accuses Baudrillard of a “super-realism,” which transposes facticity for contingency—an absolute and irreconcilable gap between appearance and reality (49). Instead, Hall argues for an “endlessly sliding chain of signification” where there may be no final meaning, but that meaning still exists. He likes Baudrillard’s assertion that “Above- and under- ground is not a very useful way of thinking about appearance in relation to structural forces,” but rejects the assertion that this is because it is all appearance. The strategies Hall employs by frequently appearing on television, then, can be seen as an assertion of the modernist project’s ability to engage the popular. Hall’s “excitement that is generated by the capacity to move from one thing to another, to make multiple cross-linkings, multi-accentualities” seems in a self-reflexive way performed in his engagement with television and popular identity.

Broadcasting Infrastructure for the Avant-Garde

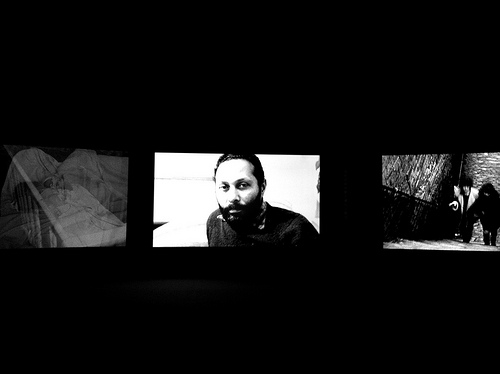

I became very interested in Stuart Hall’s work earlier this year when I saw The Unfinished Conversation as part of the “Encoding/Decoding” exhibit at the Power Plant in Toronto. Taking Stuart Hall’s essay “Encoding and Decoding in the Television Discourse” as a starting point, the exhibit showcased work by black video artists such as Terry Adkins and Steve McQueen, with The Unfinished Conversation as a centre piece, a video-installation documentary on three simultaneous screens drawn entirely from archival footage depicting Hall’s own on-screen mediation, along with the cultural milieu of Caribbean diaspora, New Left activism, and jazz music of which he was a part. I was drawn to The Unfinished Conversation because it was directed by John Akomfrah, who directed the film Handsworth Songs, an experimental documentary from 1986 depicting race riots in London, which seemed to me a powerfully singular example of the need to document a violent event told from the non-position of acknowledging the impossibility of representation in documentary form, or depicting subjects who occupy a single cultural or historical identity.

The installation was extremely compelling, but it seemed to be of an entirely different persuasion than Handsworth Songs. Even though “Encoding/Decoding” was free and open to the public, I couldn’t shake the feeling that I was participating in something exclusive. It was the final day of the exhibit in a room equipped with very expensive video infrastructure in a refurbished warehouse on Toronto’s Harbourfront, and I was the only person there. I couldn’t shake this feeling, and it was only when I began to write this probe that I realized it has something to do with Handsworth Songs’ imagined public audience. Since it was produced by a publicly-funded television channel for broadcast and re-broadcast, its attempts to undermine conventional documentary form read like a justifiable antagonism today, whereas the Unfinished Conversation, which although was commissioned by the Arts Council of England, seems mandated more by artistic prestige.

The three-screen installation version of the documentary was edited and re-composed for a home viewing audience under the title The Stuart Hall Project, which has not received mainstream distribution and remains relatively obscure. In The DVD booklet for the home documentary, the political theorist Mark Fisher describes his experience of Hall’s on-screen mediation:

“Even as I was taking Hall and the popular intellectualism which he so charismatically exemplified for granted, forces that would erase the culture which enabled him to occupy a position in mainstream media were already on the march. What mattered here was not just Hall personally, but the kind of broadcasting infrastructure – which included elements of BBC, Channel 4, the Open University – that gave him a space to speak to a mass audience. Of course, this space was not gifted; it was fought for. The other side were fighting back, and the left-wing media space Hall had striven so hard to win would eventually be erased by a broadcasting culture driven by short-term success, a culture aimed at consolation and distraction” (2).

It seems that the broadcasting infrastructure Fisher is referring to, through a particular network of institutions, artists, and activists in Britain in the early to mid 1980s, allowed for a popular (read: Public) enactment of the response to postmodernism articulated by Hall. Taking Channel 4 as an example, the growing, grant-funded film sector was given an unprecedented public audience under the channel’s mandate to serve “tastes and interests not generally catered for” by other UK broadcasters. The content produced by under this mandate often appear like radical deconstructions of the tv form, from William Raban’s impressionist meditations on industrialization to Robert Ashley’s schizophrenic “tv opera” Perfect Lives. But perhaps the most aligned with Hall’s own project are the 16 films produced by the Black Audio Film Collective, of which Handsworth Songs was the first. Through the deconstruction and radical reinvention of television tropes, these films seem to take up the “implosion of meaning” generated by the postmodernist moment, and challenge what is determined to be culturally marginal. But much like Stuart Hall’s critique of Baudrillard, they do not revel in a state beyond meaning or language, but rather, take the difficulty of representation as their project, and seek to uncover what they can from personal memory, marginalized voices, fragmentary images, and new languages.

Two More Black Audio Film Collective Films (For the Interested)

Reece Auguiste’s Twilight City is an experimental documentary or essay-film commissioned by Channel 4 in 1989. Weaving in and out of archival footage, interviews, and poetic narration, the film attempts to depict London at the end of the Thatcher era as a psychic space rife with uncertainty. The film is framed by a correspondence between a mother, who decided to leave London for her home in the Dominican Republic and wants her daughter to travel with her, and the daughter who grew up in London and is puzzled by what a trip could mean. Through interviews with intellectuals and activists, a sense of what it might mean to live a life without signification and meaning as a member of the Caribbean diaspora in the centre of European affluence.

Who Needs a Heart? takes the group’s suspicion of documentary evidence even further. The group describes the film as a “parable of political becoming and subjective transformation” that “explores the forgotten history of British Black Power through the fictional lives of a group of friends caught up in the metamorphoses of the movement’s central figure, the countercultural anti-hero, activist and charismatic social bandit Michael Abdul Malik, formerly known as Michael X and christened Michael De Freitas, who left England in 1970 and was tried and executed for his role in an unsolved murder in Trinidad in 1975.” By experimenting with form within the representative medium of documentary, the BAFC undermine received notions of what counts as verification or documentation. And while it seems very much in the spirit of a postmodern skepticism of the referential status of art, it doesn’t take any pleasure in it. Instead, it seems that the “dispersed multiple identities, radical contingency, and irreducible ludic plurality of struggles” mentioned by Zizek serve as a kind of starting point from which glimpses of meaning can still be achieved. While the visual aspect of the film is drawn primarily from archival footage—visual evidence as a trace of the real—the audio is constructed through avant-garde composition that stands as a trace of something else—personal memory or the gaps in recorded history itself. Through the manipulation or excision of diegetic sound, the film challenges representations of the British Black Power movement that try to contain or dismiss it.

Works Cited:

Akomfrah, John. Handsworth Songs (Channel 4, 1986)

—Who Needs a Heart? (Channel 4, 1991)

—The Stuart Hall Project (British Film Institute, 2013)

Auguiste, Reece. Twilight City (Channel 4, 1989)

Born, Georgia. “Strategy, positioning and projection in digital television: Channel 4 and the commercialisation of public service broadcasting in the UK,” Media, Culture & Society 25:6 (2003): 778

Fisher, Mark. “On Stuart Hall.” The Stuart Hall Project, British Film Institute. Pamphlet. 2013.

Grossberg, Lawrence. “On Postmodernism and Articulation: An Interview with Stuart Hall.” Journal of Communication Inquiry 10 (1986): 45– 60.

Julien, Isaac and Mercer, Kobena. “De Margin and De Centre.” Stuart Hall: Critical Dialogues in Cultural Studies. Eds Morley, David and Chen Kuan-Hsing. London: Routledge, 1996.

Slack, Jennifer Daryl, and J. Macgregor Wise. “Agency,” “Articulation and Assemblage.” Culture + Technology: A Primer. New York: Peter Lang, 2005. 115–33.

Zizek, Slavoj. “Class Struggle or Postmodernism? Yes, please!” Contingency, Hegemony, Universality: Contemporary Dialogues on the Left. London, Verso: 2000.

“a culture aimed at consolation and distraction” What could be more sad.

I enjoyed your probe since I’m also interested in the idea of alternative discourse, and I was able to link many of the ideas and themes that I’ve been navigating in my own probe this week with what you describe as “an aesthetic movement’s self-conscious rejection of the past and the evocation of the new is a defining hallmark of modernity”. The Unfinished Conversation and other works from the same movement you explore, have much in common indeed with the Palestinian revolutionary films made in the 1970s, especially They Do Not Exist, which similar to the film you write about, functioned specifically from a non-position in postmodernist sense. It was created to force the reality of a Palestinian existence upon a dominant narrative that insisted there wasn’t such an existence. As such the Palestinian filmmakers of this movement, and particularly in this film, grapple with the impossibility of representation in docu-fiction form in order to depict themselves as subjects who, as you wrote in relation to your film, “occupy a single cultural or historical identity.”

As such, I also believe the modus operandi of the Palestine Film Unit was in their all-encompassing objective to expose the Israeli occupation of Palestine as unjust and violent. This is best summed up by you in relation to the film you write about in that it “seemed to me a powerfully singular example of the need to document a violent event told from the non-position of acknowledging the impossibility of representation in documentary form, or depicting subjects who occupy a single cultural or historical identity.”

So, indeed, by reflecting upon the relationship between colonialism and discourse, Hall would say we’re just in a more advanced stage of modernity; we’re not really even close to being truly post-modern yet…

I enjoyed your probe since I’m also interested in the idea of alternative discourse, and I was able to link many of the ideas and themes that I’ve been navigating in my own probe this week with what you describe as “an aesthetic movement’s self-conscious rejection of the past and the evocation of the new is a defining hallmark of modernity”. The Unfinished Conversation and other works from the same movement you explore, have much in common indeed with the Palestinian revolutionary films made in the 1970s, especially They Do Not Exist, which similar to the film you write about, functioned specifically from a non-position in postmodernist sense. It was created to force the reality of a Palestinian existence upon a dominant narrative that insisted there wasn’t such an existence. As such the Palestinian filmmakers of this movement, and particularly in this film, grapple with the impossibility of representation in docu-fiction form in order to depict themselves as subjects who, as you wrote in relation to your film, “occupy a single cultural or historical identity.”

As such, I also believe the modus operandi of the Palestine Film Unit was in their all-encompassing objective to expose the Israeli occupation of Palestine as unjust and violent. This is best summed up by you in relation to the film you write about in that it “seemed to me a powerfully singular example of the need to document a violent event told from the non-position of acknowledging the impossibility of representation in documentary form, or depicting subjects who occupy a single cultural or historical identity.”

So, indeed, by reflecting upon the relationship between colonialsm and discourse, Hall would say we’re just in a more advanced stage of modernity; we’re not really even close to being truly post-modern yet.