The Strange Case of Holbein and Lockey: Sir Thomas More and His Descendants and Its Descendants

In his “Editorial: The Value of Forgery,” Jonathan Hay argues that the presence of forgeries in the canon alongside putatively legitimate artworks calls into question the category of genuine on which the valuation of art depends. He argues that “the coherence of the modernist history of genuine art depends on elision of the feedback loop through which forgery intervened and continues to intervene in the space of the genuine” (6), suggesting that the conventional view of the art canon is that it is indeed such a “space of the genuine,” that there should be no place within it for works of dubious or problematic origin, whatever their intrinsic aesthetic value or substantive contribution to the discourse of art history. Hay’s project is in part, then, to challenge traditional Western notions of art and artist: that only “genuine” and unproblematically attributed works have a place in the authorized canon, and that decisions about value and placement within the canon can be made with reference to a reliable, stable and uncomplicated conception of the author function.

Hay intends to “make a case for seeing forgeries as art” (5), acknowledging the need to “conceptualize artistic value differently from usual. . . . potentially decentering our understanding of the history of art in general” (5). He points out that “[t]he understanding of the artistic past that artists and artisans possessed has often been contaminated by the unrecognized presence of forgeries in the artistic archive” (6)—that there is a pure concept of the author function that we attempt to bring to art but that art somehow defies or resists. The relationships between makers and made objects are too fraught to permit such a pure notion of the sanctioned, identifiable artist and the fully attributable art object.

Hay’s theorization of forgery in art rests on a conception of the artwork’s relationality that acknowledges these complicated relationships between art and artist, and his consideration of the status of forgeries as art involves a fluid and elaborate idea of the author function. The salient aspect of Hay’s relational theorization of art for our purposes here is the suggestion that

every explicit copy is coauthored. It makes no difference whether the copyist is unknown, can be identified, or made his identity known. Coauthorship is equally indifferent to whether the original artist is known, unknown, or misidentified. Nor does it matter where the copy is located on the spectrum that runs from replica to free copy. “Copyist,” like “artist,” is a potential fulfillment of the author function, and the only feature that separates copy cultures where artworks reiterate a rare artistic event from cultures in which such events have become the norm is that copy cultures did not make a clear distinction (or sometimes any distinction) between these two contrasting conditions of authorship. (6)

An artistic canon that includes forgeries is one that admits a more complex definition of the author function such as the one at work in the sort of “copy cultures” that Hay refers to here. While Hay is specifically focused on forgery, “an artwork that fraudulently passes itself off as genuine” (5), I am interested in looking at how we might extend some of the claims he makes about relationality and “coauthorship” to cases of reproduction that do not involve such “deceit in the space of art” (6). Hay’s ideas, brought to bear on an intriguing case of duplication “outside the frame of criminality . . . or deviance” (6) might lead us to more elastic conceptions of the author function and the means by which works whose authorial derivations are dubious or problematic might nonetheless cross through the liminal territory of the “paramedium” (10) and into the “authorized” canon of the genuine—a concept we might also reframe so that it denotes the products of more complex relationships between artist and art object.

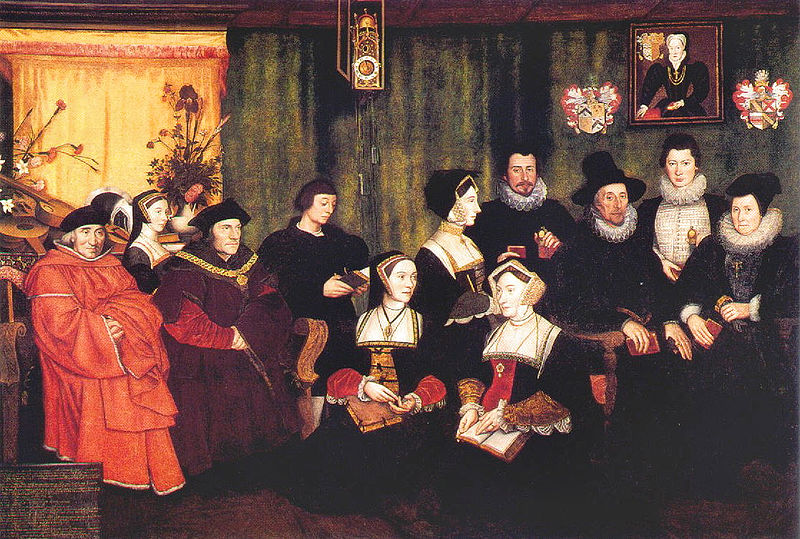

As a case study with which to explore these ideas, I’ll offer a painting, rather a constellation of discrete but related paintings, called Sir Thomas More and His Descendants. There are in fact three of these, c. 1593-4, all of them copies by the English artist Rowland Lockey of a now lost painting from the 1520s by Hans Holbein the Younger depicting Sir Thomas More and his family. Lockey is mainly known for producing copies of artworks for the private “long galleries” of wealthy English families, and all of his copies of Holbein’s painting were commissioned by Thomas More II, Sir Thomas More’s grandson: “the exact copy now at Nostell Priory, the National Portrait Gallery picture, and a miniature which closely resembles it” (qtd. in Honigmann 81). Below is the copy at Nostell Priory in West Yorkshire:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:More_famB_1280x-g0.jpg

Below is the one in the National Portrait Gallery in London:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sir_Thomas_More_His_Father_Household_and_Descendants.jpg

Finally, below is the cabinet-miniature version (c. 1594) in the Victoria and Albert Museum:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Rowland_Lockey_Thomas_More_and_Descendents.jpg

Hans Holbein the Younger arrived in England in 1526 “with an introduction from Erasmus to More” (Honigmann 81), and he received the commission from Sir Thomas More for the family portrait, the preparatory study for which, according to Angela Lewi, must have been completed by February 1528 (qtd. in Honigmann 81). The completed Holbein painting was destroyed in a fire in the eighteenth century, and all that remains today as part of this collection of images that is Holbein’s own work is this study:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hans_Holbein_d._J._-_Study_for_the_Family_Portrait_of_Sir_Thomas_More_-_WGA11595.jpg

The odd relationship between these four linked images is of particular interest here in connection with questions of authenticity and inauthenticity, originals, copies, fakes, and the author function; considered together as part of an oddly “coauthored” corpus, the study, the lost Holbein painting and Lockey’s copies ought to offer us an opportunity to explore the questions that Hay raises about the problems of the author function and the untenability of “genuineness” as the guiding principle of canonicity.

First, the sketch is an uncontested Holbein, but it is a lesser duplicate work that merely adumbrates the lost painting that later served as the basis for Lockey’s copies, and while the sketch bears the authorial mark of Holbein, and “authorizes” the Lockey images in that its content confirms the relationship of the Lockey copies to the lost Holbein original, it is ultimately itself an unrealized piece of work. However, this preparatory sketch precedes the lost painting in time; viewed in chronological sequence, the lost painting is a kind of copy, a duplicate of the composition depicted in the study. Each Holbein image involved here, then, is arguably an original and a copy, from particular points of view and with respect to different ways of assigning relative value and primacy to sequential and compositionally related works.

In any case, second, the lost painting serves as the original of which Lockey’s works are copies. The Lockeys are reproductions of the Holbein, but as the only extant paintings in the collection—the exhibited works that stand in for the absent Holbein—they form the centre of this cluster of related paintings. They are the fully realized images in the collection and the linchpin holding that collection together, but they depend entirely on Holbein’s lost image, in part by virtue of their status as known copies (what Hay might call their relational nature vis-à-vis Holbein’s work), and, where canonicity and artistic legitimacy are concerned, in part by virtue of Lockey’s relative obscurity and Holbein’s considerable fame. The Lockey images too, then, are both originals and copies in their ways. Distinctions between original and copy, and between artist and copyist, seem to break down here, just as the distinction between the individual painters themselves also seems to break down, a point underscored by the fact that the Wikimedia Commons page for the Holbein sketch lists the Lockey copies as “other versions” of the same image to be considered together for the purposes of usage permissions, public-domain status, and so on.

Hay mentions that the “absence of a dependable author function” (7) accounts for the art world’s reluctance to accept works like forgeries as art, and he makes clear the political and ontological problems of authorship introduced by forgery, by “deceit in the space of art” (6). The strange case of Holbein and Lockey permits us to consider some of Hay’s ideas about genuineness, originality, canonicity and relational value “outside the frame of criminality . . . or deviance” (6), in connection with non-deceptive but nonetheless problematic absences of a “dependable author function.” What are we to make of these images taken together, as each both establishes and destabilizes the relational configuration of others in the collection in terms of originality, primacy and “authority”? What role does Holbein play in “authorizing” the Lockey images, as we acknowledge the inconceivability of discussing Lockey’s images outside the context of Holbein? How might our considerations of the complex “relational” author function in this peculiar body of works extend to the commissioners of the images, Sir Thomas More and Thomas More II, in whose very names one hears echoes of the relationships of originality and duplication that their commissioned paintings invite us to consider? Such questions may help us map out a canonical territory for the “undependable” author function, which proves to be based on a thornier and more involuted sense of authorship than the one implicit in traditional conceptions of the canon.

Works Cited

Hay, Jonathan. “Editorial: The Value of Forgery.” RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics 53/54 (2008): 5-19.

Honigmann, E. A. J. “Sir Thomas More and Contemporary Events.” Shakespeare Survey 42 (2002): 77-84.