Other People’s Preserves: The Citation Economies of a Canning Blog

Unlike most methods of preparing and cooking food, preserving — the practice of canning, pickling, fermenting and drying food — allows for the long-term storage seasonal produce. This temporal dimension specific to preserving has its roots in “historical” practice: these processing methods pre-date the widespread availability of refrigeration technologies, agro-industrial supply chains, and the perpetual harvest of modern supermarkets. The practice relies on biological and thermodynamic processes to stabilize perishable food. As such, while recipes for jams, jellies, pickles and chutneys may vary in terms of their ingredients and flavor profile, processing methods remain consistent: high sugar content for preserves, a low pH for pickles; processing in a hot water bath or pressure cooker; and a good seal. To a certain extent, these recipes change little over time and prove resistant to changing culinary tastes. At the same time, changing USDA food safety regulations and technological innovation (like pressure cookers and the Kerr canning ring) drive republication. The favored guide, the Ball Blue Book Guide to Preserving was first published in 1909 and is currently on its 37th edition.

As a descriptive and instructional form of writing, recipes pose a particular problem in terms of intellectual property vis-à-vis their relationship to real objects. Due to their short length and shared techniques, recipes tend to repeat formal characteristics and whole segments of text. In practice, any deviation from an existing recipe that results in a new object can be claimed as a new recipe. Apple cider vinegar will be substituted for white vinegar in pickles or honey for refined sugar in jams. Two recipes will be combined to create a new variation on the iconic red pepper jelly. A French compote recipe will be updated to American food safety standards. For food blogs and online recipe caches, this issue is compounded by the medium’s lack of fixation. Ostensibly, the blogging platform serves as the “tangible medium” described by copyright’s fixation requirement (Murray & Trosow 42), however the shifting position or that of a blog entry on an infinitely scrolling page or of a blog in a search index confers a sense of impermanence on these works. At the very least, this impermanence impedes a user’s ability to locate and exploit the entry over time. To compensate, canning blogs operate within a citation economy where authors routinely link a recipe with previous entries. This practice reveals both a recipe’s genealogy and a network of recipe producers.

“Internet links are one endless chain of footnotes, only handier. Blogs invite their readers to trace back through their sources like any good academic historian.” (Murray 177-78)

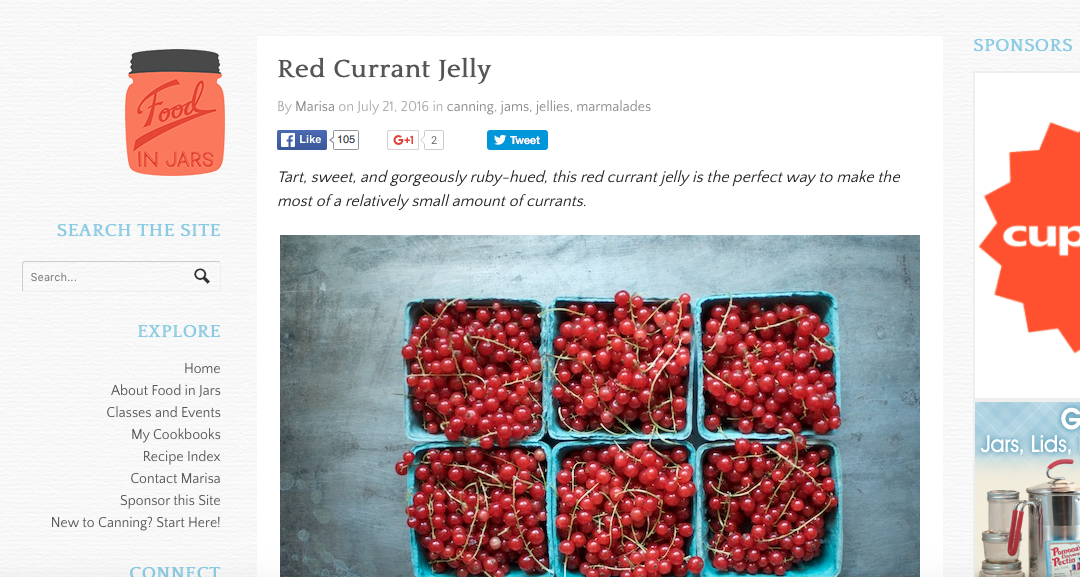

Consider the linking practices of a popular canning blog, Food in Jars, run by Marisa McClellan. In her Red Currant Jelly recipe, McClellan refers to a published recipe book, Pam Corbin’s The River Cottage Preserves, as a source for specialized knowledge for processing hard-to-find fruit in North America, in this case the red currant. As a published author of several canning books, McClellan uses links in her recipes to refer readers to other equally authoritative sources or to similar recipes she has published on other platforms (such as the recipe for Spicy Peach Barbecue Sauce on Ball’s canning blog, Freshly Preserved Ideas, or the Garlic Dill Refrigerate Pickles tutorial and recipe she wrote for The Kitchn).

In addition to these references, McClellan also provides her readers with a “weekly roundup” of links: new recipes, affiliate links, and canning inspiration. These lists consist of 10-12 recipes found on other canning blogs, lifestyle blogs, or a publisher’s site; or recipes digitally reproduced from print collections. Occasionally, one of these links will come from a posted recipe in which McClellan is referenced by an author, as is the case here and here.

In her chapter on the gaps and overlaps between citation economies and copyright law, Laura Murray characterizes the citation system used by bloggers as a “reputation economy” in which cultural capital is bestowed on identified “sources” through hypertext links (174). Cultural capital, rather than economic capital as in the copyright system, because attribution relies on free, cited circulation and “does not result in direct payment” for the source (174). In this sense, citation systems intersect and interact with market systems but function independently of intellectual property law (174-75). Her use of blogging and hypertext practices as examples of a citation economy is interesting considering how monetized blogging has become. If attribution does not directly result in monetary compensation for the original source, monetized linking practices can directly influence the income of the blogger, as well as benefit their reputation.

Search Engine Optimization (SEO) theory — the set of rules through which bloggers “understand” the algorithms running search engines and could affect their placement on search results — dictates that an website’s influence and authoritative value is governed in part through the number of third-party websites which link back to the site. Whether or not this is the case, this aspect of SEO has shaped the way in which blogging communities relate to one another — driving a “gifting” or exchange economy. In this economy, bloggers are encouraged to write guest posts to other sites and link to peer blogs through profile pieces and weekly link round-ups to encourage these blogs to “link back.” Furthermore, professional bloggers have monetized these peer-to-peer relationships: guest posting has turned to paid ambassadorships or publicity; links and recommendations have turned into affiliate links, wherein the author is remunerated for reader click-throughs and purchases; and blog posts are interspersed with native advertising and sponsored content.

Effectively, within this “reputation economy,” it becomes impossible to discuss a citation economy divorced or extracted from a market economy as Murray argues. The monetization of blog citations moves beyond the co-opting of a citee’s authority by the citer and highlights the paradox of Bensman’s 1988 essay on citation economies: whether one considers the ideological or economic context a factor in the construction of citation networks, there is no unbiased perspective from which to ascertain their possible objectivity through our own implication in these systems. (Or, in his words: “Whether a theme is proven or disproven by a self-conscious distortion of documents referred to in a text is not merely a matter of technical proficiency, but one which strikes at the heart of the entire scholarly enterprise. But when ideologies are involved, judgment as to what constitutes an accurate representation of the evidence and of particular sources, is itself conditioned by the ideologies and ideological causes which may lie outside of scholarly proficiency and even self-conscious dishonesty” (449).)

At the heart of this concern, is the relationship between author and the field of production — and its expression through citation networks. What troubles Bensman on a practical level is an author’s ability, through these citation networks, to misrepresent a field of knowledge through “elitist” references or “deviant” citations. Underlying this concern is the troubling realization that a field of knowledge is a virtual construction produced by citation practices — the “social construction of reality” of a scholarly field.

“Yet because of the range of choices available to the citer (and the ongoing structure of citing behavior) this input [citation] can determine, if only in part, the output, the continuously emerging structure and culture of a field, also seen as a social reality.” (443-44)

Bensman’s article is an interpretive declension of the relationship between an individual author and a field of knowledge through the lens of citation practices. For him, the vertical or horizontal stratification of a field and legitimation is not solely produced by citations, but by ideological factors and personal motivations in a biased network of shifting relationships.

Interestingly, Bensman does not use the term “network” to describe the “input” and “output” of citations (nor is he gesturing towards actor-network theory in the way that I’m implying), but he does apply the term to the “social networks that exist in a field,” in the same sense as “networking” that in his understanding functions similarly to the “academic structures” or “‘party’ lines” that affect an author’s citation economy. Writing thirty years later, Murray draws the comparison between academic citation and networked hyperlinks in her essay: “Internet links are one endless chain of footnotes, only handier” (Murray 2008 177). What does it mean, then, to say that citation economies function conceptually as linked networks in academic writing?

My interest in discussing the citation economies of a canning blog has been to consider — along the lines of Bensman’s problematization of the relationship between individual author and field of knowledge — how the remediated relationship between author, publisher and platform affects citation practices. Murray’s comparison of academic citations to hyperlinks makes an example like the canning blog so compelling as the mediated network can be followed, travelled, and interrogated. However, as a platform blogging remediates the relationship between author and publisher since authors also fulfill the roles of publishers. In the case of Food in Jars, McClellan determines the form, serialization and style of all content on her blog and negotiates her own relationship to advertising interests as well as produce content. This rearticulation allows the singular author full control over the citation networks published on her blog. It is this authorial-editorial control that sets the canning blog or lifestyle blog apart from publications such as the culinary section of other digital media.

Bibliography

Bensman, Joseph. “The Aesthetics and Politics of Footnoting.” International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society 1.3 (1988): pp. 443-70.

Murray, Laura. “Plagiarism and Copyright Infringement: The Costs of confusion.” In Originality, Imitation, and Plagiarism, edited by Caroline Eisner & Martha Vicinus. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2008. pp. 173-180.

Murray, Laura & Samuel Trosow. Canadian Copyright: A Citizen’s Guide. 2nd Rev. Edition. Toronto: Between the Lines, 2013.