Copy & Paste & Play: Amateur Games as Appropriation Art

Independent game-making has, despite its relatively short history, seen a significant evolution. “Indie” games, as they are known, are now associated with such popular titles as Minecraft (2011), The Stanley Parable (2013), and Don’t Starve (2013) – games that have unquestionably penetrated mainstream consciousness. There is a certain sophistication associated with the Indie genre nowadays, with more and more titles whose end results are often capable of rivaling the sheen of commercial games. Crowdfunding facilitators such as Kickstarter or GoFundMe allow for the possibility of significant financial backing from the general public, changing the economic landscape in which independent games are made, and consequently shifting the characteristics that make up an indie game.

Prior to the popularization of crowdfunding or online distribution platforms like Steam, indie games took on a different form: they existed as games made in Flash, or as text adventures played in an internet browser, or as games cobbled together on free (or pirated) rudimentary game-making software, such as GameMaker or RPGMaker. These games were often the passion projects of one-man teams, with the prospect of putting them on the market mostly nonexistent. As such, the economic realities in which these games were made differ vastly from the games dominating the indie scene today. These kinds of games – specifically those made with RPGMaker – are the form I intend to explore in this probe, and to use as an argument for their status as appropriation art.

William Landes, in his essay “Copyright, Borrowed Images and Appropriation Art: An Economic Approach” describes ‘appropriation art’ as such:” Appropriation art borrows images from popular culture, advertising, the mass media, other artists and elsewhere, and incorporates them into new works of art. Often, the artist’s technical skills are less important than his conceptual ability to place images in different settings and, thereby, change their meaning. Appropriation art has been commonly described “as getting the hand out of art and putting the brain in.” ” (Landes 2)

While Landes’ discourse does not touch on games as an art form, his definition fits the subset of indie games described above to a tee.

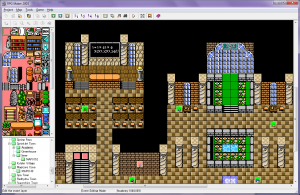

RPG Maker 2003 at work. The tileset is displayed in a pallet on the left, and the user can select each tile to ‘paint’ the map on the right.

RPGMaker is a series of software created by the groups ASCII and Enterbrain that allows for the relatively easy development of role-playing video games. While the latest iterations of RPGMaker (XP, VX, MV, etc.) are available through distribution services like Steam, earlier versions (RPGMaker 2000, 2003, etc.) were harder to come by legally and were often pirated. The software’s interface is purposefully intuitive, allowing a player to easily craft maps from tilesets, program events through the selection of options from a menu (‘Show Message’, ‘Change Character HP’, ‘Play Sound Effect’, ‘Open Main Menu’, etc), and edit playable characters, enemies, and other resources through an organized database. The software requires little knowledge of coding, though later entries in the series would allow for advanced programming via an internal scripting language, the use of which was entirely optional.

The ease of use afforded by the software and the relatively easy accessibility of it (assuming one was comfortable with piracy), meant that there was soon a quiet explosion of RPG Maker games on the internet, populating a preliminary wave of what would be considered the “indie” genre. The RPG Maker games that were released as part of this wave, which I’m going to capriciously place as occurring in the early 2000s, were of a particular nature that was almost inherently appropriative, and were backed by an infrastructure that both enabled and encouraged this appropriation to take place.

In short, the RPG Maker games I’m referring to made egregious use of the resources of other commercial, industry-made games. The reasons for this stem from the claims I’ve made above: creating a game with all-original resources – and by resources I mean graphics, pixel art, tilesets, sprites, animations, sound effects, background music, window skins, fonts, etc. – is simply too tall a task for the one-person hobbyist teams who were creating these games. Games often require whole teams of people to tackle even one of the resources I listed above, in addition to additional software and a whole lot more time. As Landes says:

“These works all have in common what economists call a “public goods aspect” to them. Creating these works involve a good deal of time, money and effort (sometimes called the “cost of expression”). Once created, however, the cost of reproducing the work is so low that additional users can be added at a negligible or even zero cost.” (Landes 4)

As such, it became common practice for members of online game-making communities to ‘rip’ assets (sprites, tilesets, etc.) from pre-existing games, rearrange them in such a way that they are legible to the RPG Maker software, and distribute them online, free of charge, often simply asking for credit. Game makers would then import these resources and use them to craft their own games, resulting in games that were unique chimaeras of familiar imagery taken from other video games. Landes asks us to consider the following case, which I include here as an apt analogy for what was taking place when these kinds of games were created: “Consider first the case of an artist who incorporates a copyrighted photograph from, say, a popular magazine into a unique collage. The artist removes the actual image from the magazine, affixes it to a board and adds other objects, colors and original images. No copy of the photograph is made and the photograph itself may constitute only a small part of the collage” (Landes 12-13).

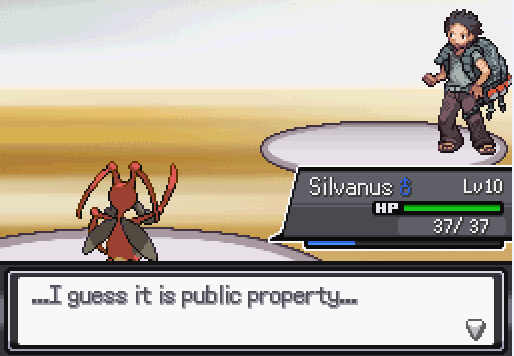

This shot alone includes resources from Pokémon Red/Blue/Yellow, The Legend of Zelda: Link’s Awakening, Final Fantasy Adventure, and Final Fantasy Legend

These games were often distributed within insular RPG Maker online communities, never for the purpose of turning a profit and never quite breaching the mainstream, and therefore never quite coming under the scrutiny of the developers whose intellectual property was being blatantly appropriated. One must take into consideration the cross-cultural nature of these games as well: as in the example above, the graphics put to use in Eden Legacy: A Knight of Eden were all ripped from Japanese games, then applied to an English-language, western-produced amateur RPG downloaded by an approximately 1,000 people (as per its download stats on RPGMaker.net); as such, the chances of companies like Square-Enix or Game Freak taking notice – much less taking legal action – were relatively slim.

As Landes puts it, this process inevitably became one of “conceptual ability to place images in different settings and, thereby, change their meaning” (2). The lifting of familiar symbols such as the sprite of the protagonist from the early Pokémon games and using it for the protagonist of a game set in a world of medieval fantasy reconfigures the meaning of the sprite. As a player of RPG Maker games, you are exposed to a unique language communicable only to those with a particular vocabulary – in this case, the reconfiguration of the Pokémon sprite only truly occurs if you have played and are familiar with the Pokémon game from which it originates. As in the above example, games rarely simply aped a single game’s assets (though those do exist, particularly when the intent is to create a fangame), but instead combined the resources of several to create a unique, if jarringly familiar, pastiche.

Marcus Boon, in his book “In Praise of Copying”, writes of the putting together of a mixtape or iTunes playlist in a way that I think reflects the philosophy of these RPG Maker amalgamations: he notes that the process of making a mixtape is “intimate” and “emotionally charged”, and that “the mixtape maker has available in accessing the variety that is essential to copia, and straight out of a classical rhetoric manual: inventio (the selection of tunes to be played), dispositio (the ordering or sequencing of them), and elocutio (the cuts and edits made, but also the loving care put into the handwritten cover, the decoration of the cassette), all deployed in order to charm the recipient of the tape” (Boon 55). Just like the mixtape-maker, the RPG Maker game designer carefully selects the assets they’re going to copy, rearranges and reorders them in new configurations, and also omits, edits, and personalizes these resources to make a product that is uniquely theirs.

These chimerae were not isolated instances either, as they were supported by an insular infrastructure that facilitated the practice of appropriation. Databases like Charas Project came into existence to archive and distribute user-created ‘rips’of resources, specifically formatted for use in RPG Maker. More broadly, sites like The Spriters Resource compile ripped graphics of games from a multitude of systems for personal use. As Boon puts it, “What appears to be on offer on the Internet, what fuels its imaginal space, is the utopia of an infinite amount of stuff, material or not, all to be had for the sharing, downloading, and enjoying. For free” (Boon 42) – he clarifies subsequently that naturally what appears to be ‘free’ is only being perceived as such, for ‘free’ implies a degree of consent on the part of the original artist, the likes of which are not found on these online databases full of ripped video game assets

RPG Maker game Final Fantasy Black Moon Prophecy, a fangame of the Final Fantasy series, makes use of assets from Final Fantasy IV, released 25 years ago as of the writing of this probe. The fangame uses a tileset from the game’s town maps, safe zones for the player to recover their strength and restock on items. Black Moon Prophecy, however, edits the tileset and then uses it to map one of the game’s dungeons, Niflheim (Left), a decaying town in which monsters abound. This is another instance of familiar iconography being reconfigured and given new meaning – note the re-use of graphics between Niflheim (Left) and Final Fantasy IV’s town of Baron (Right)

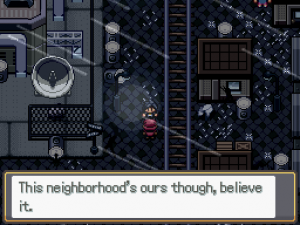

To further illustrate the case for amateur games as appropriation art, I look to a popular fangame currently in circulation: Pokémon Reborn. The game, created in RPG Maker XP by a team of amateur developers, describes itself as such:

“Pokemon Reborn is a Gen 3-styled downloadable game featuring all content through Gen 6. Experience a never-before-seen layer of strategy with the all-original Field Effects, using the terrain to outplay and overwhelm your opponent! Collect, train and battle with all 721 Pokemon available in-game and take on Gym Leaders of all 18 types as you fight to restore Reborn to prosperity!”

Its setting is described as a city wherein “black smog and acidic water garnish the crumbling structures” and “city streets fest like alleys with disaster and crime”. Among its list of features are “Increased Shiny chance”, “Visible IVs/EVs”, and “18 Type Gyms”. While the significance of those features or the grim backdrop painted in that description may be lost on those who have little familiarity with the Pokémon video games, the promise being made is that Reborn offers an experience that’s familiar enough to appeal to fans of Pokémon, but different enough that it acts as a salve to those who believe the official Pokémon games to be lacking.

Fans of the series have often wanted exactly what Reborn is providing: a Pokémon game that reflects the more mature demographic of its player-base, the ones who might not be so enthused by the colourful, saccharine settings in which the games usually take place. The fangame makes copious use of the official games’ properties – from sound effects to tilesets to the Pokémon themselves – and does a shockingly thorough job of mimicking the games’ mechanics, menus, and gameplay elements, but through graphical edits, brand new level designs, and a unique and original story, reimagines the Pokémon narrative in a way that may appeal to different parts of the Pokémon-playing demographic, all while allowing for an experience that’s sufficiently familiar. Similarly, the game features enhanced difficulty as a response to accusations that the original games are too easy and child-like; the game also offers features such as the ability to play as a character of a non-specific, non-binary gender identity, a feature that few commercial games offer. In this context, we can see appropriation art performing an important and unique function: fulfilling the particular demands made of the original art, to which the original artist(s) have not responded.

Notes:

[1] Also up for a similar kind of examination are webcomics, particularly the ‘sprite comics’ that were popular in the early 2000s: Bob and George, 8-Bit Theater, Zelda Comic, etc. These internet-born comics also made use of video game resources, notably the character ‘sprites’ from which they get the title of their genre, and not only reconfigured their symbolic meaning but transported them to an entirely new medium, that of the comic. 8-Bit Theater, for example, reimagined the entire narrative of Final Fantasy, giving voice to previously mute characters and offering a wholly new and innovative interpretation of a familiar world using familiar iconography. Zelda Comic, on the other hand, made use of resources from multiple games, including the titular Legend of Zelda as well as Kid Icarus and Bubble Bobble, creating a unique pastiche wherein several cultural icons could interact with one another.

[2] It’s worth noting that these indie games are not only economic to make, but also to play. As these games cannot legally be distributed with a pricetag, and yet offer content hefty enough to rival commercial games (Reborn boasts over 48 hours of gameplay, and has yet to be completed), gamers can enjoy these games without shelling out the money that is required to purchase the game as well as the console on which the game plays. This is especially true of Pokémon games: the official games allow for only one save file per cartridge, hampering replayability as, assuming the player does not want to lose their data, they are required to buy an additional cartridge to replay the game. Reborn circumvents that, as save files can be exported and imported, and its very existence as a free-to-play game makes it a suitable remedy for the Pokémon fan who’s itching to play again but is unable or unwilling to pay for another cartridge.