Mountbatten probe

YouTube video for context

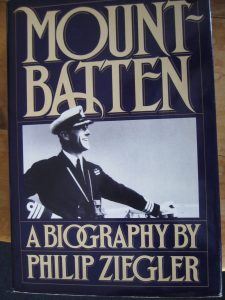

The first artefact from the Mordecai Richler collection that I choose to look at is the biography of Earl Louis Mountbatten of Burma. It is a weighty tome, 756 pages, about one and a half kilos, hard cover with book jacket, described by the author as ‘massive. The size is a conventional 6.5 x 9.5”, 2 inches thick, published in 1985:

first photo

Richler’s first edition describes it as A Biography, whereas the UK origin second reprint emphasises that this is the official biography. In the Richler collection copy, a north American edition, Mountbatten is pictured as a Commander in the Royal Navy in 1932, a much more dashing version than the second printing of the much older Mountbatten with his admiral’s epaulettes and more serious expression, perhaps reflecting the excitement of the new world and the nostalgia of the old, and their different markets.

There is no annotation in this book and it shows little sign of use. Richler may never have opened it. The cataloguers put it in ‘World History,’ and that is a good decision. Mountbatten’s story is much more than World War II.

As Gerard Genette suggest in Paratexts, the title and subject for the book carry the authority of someone who is a household name in England for his mostly distinguished naval career; that it was written by the Eton and Oxford educated author of Addington and King William IV, Philip Ziegler, ensured a wide readership. It would not have sold so well as ‘First Sea Lord’ (Genette 2, 7-8).

Professor Wershler, in conversation, suggested that the position of the book on the shelf, and enquiry into adjacent volumes might be revealing. Here is Mountbatten’s shelf:

Second photo

The librarian positioned Mountbatten at the opposite end of the shelf from the 1997 biography of his wife, Edwina Mountbatten. He was married to his work, and she was a magnificent partner in this endeavour, but as Ziegler says, overbearing in the marriage; in short, Mountbatten was a lonely man (Ziegler 483, 693). As both Ziegler and the author of Edwina Mountbatten, A Life of her Own, Janet Morgan, agree, the real love of her life was Jawaharlal Nehru. ‘If there was any physical element it can only have been of minor importance to either party,’ Ziegler says, somewhat stuffily (473). Morgan says nothing like that happened, indeed, at that time and place it would have been unthought of. Lady Mountbatten and Nehru did correspond daily, and the letters were ‘rhapsodic but chaste,’ but they denied themselves physical passion (Morgan 440).

Mountbatten is also lonely on the shelf, separated from Edwina by other failed partnerships: Katherine of France is left with a babe in arms when Henry V dies of dysentery fighting in France, Henry VIII murders the subject of his adjacent book, his Queen Anne Boleyn, Elizabeth I’s decision to avoid a partnership led to the public execution of her nephew’s son, and the volume of Wallis and Edward reflect the values of which Louis disapproved (Ziegler 96). Edwina had left-wing tendencies, so she would not have minded her biography next to that of Aneurin Bevan, the welsh coal-miner’s son (502). On the surface the Lord Louis and Edwina cooperated well, but as Morgan says, ‘Dickie’s chief failing was that he was not Nehru’ (Morgan 436).

From today’s excerpt from The System of Objects, how does Mountbatten satisfy Baudrillard’s proforma for collecting? It does add authenticity to Richler’s knowledge of twentieth century history, it could be one of a series if linked with the biography of Mountbatten’s wife, and may have a connection to nostalgia; Richler did write an anthology of writings about World War II (Baudrillard 75, 88, 95). It does not seem to be a passionate acquisition, it is not annotated, and it has no discernible intimacy (87-8). We also have to ask if Richler was impoverished or inhuman because he collected books? (106). I don’t think so.

Elsewhere in Baudrillard, we could also ask if we think the Richler Collection has a style, how far do we think the collection was manipulated by the collector, did it give him gratification and does it constitute a Richler brand? (147, 153, 177, 191).

How far is Baudrillard relevant to Richler as collector? The Richler collection is principally books, and Mordecai Richler was an avid reader, as Charles Foran’s biography of him demonstrates (Foran 85-6, 201, 568). According to Foran, Richler was more a collector of stories for his writing than a collector of objects.

Works Cited and Consulted

‘Mountbatten: Death of a Royal’ A Documentary. YouTube, uploaded by AngelDocs, 8 February, 2013, www.youtube.com/watch?v=V0H2SCdnKtE&t=10s.

Baudrillard, Jean. The System of Objects. London: Verso, 1996. Print.

Foran, Charles. Mordecai : The Life & Times. Toronto: Alfred A. Knopf Canada, 2010. Print.

Genette, Gérard. Paratext: Thresholds of Interpretation. New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press, 1997. Print.

Morgan, Janet. Edwina Mountbatten: A Life of Her Own. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1991. Print.

Richler, Mordecai. Writers on World War II: An Anthology. Toronto: Viking, 1991. Print.

Ziegler, Philip. Mountbatten: A Biography. New York: Alfred Knopf, 1985. Print.

Raymond B