Last February, Nintendo and Intelligent Systems released the first title in the twenty-seven-year-old Fire Emblem franchise specifically designed for mobile gameplay, and the only installment to operate on a platform other than a Nintendo console—emulation notwithstanding. As a strategy role playing game imbued with gambling elements, Fire Emblem Heroes conforms to an increasingly prevalent free-to-play (F2P) model known as the gacha game. While all but the newest players can complete the entirely of the game’s content with various degrees of ease without in-app purchases, Heroes nevertheless earned $114.9 million in revenue within its first six months, surpassing Super Mario Run—which retails for a flat $10—despite significantly fewer downloads. With the intention of interrogating how an ostensibly free game can exceed the earnings of a top-tier Nintendo IP, this probe explores how collecting operates as an incentivizing factor in gacha games that trade on pre-established intellectual property. Borrowing Nick Montford’s model for the analysis of video games as an organizing framework, this probe surveys issues of ownership, ephemerality, fan interest, and ethics to undertake a consideration of the monetization of digital collections.

Platform: On the Affordances of Mobile Technology

In 2011, Nintendo CEO Satoru Iwata declared that:

“[mobile gaming] is absolutely not under consideration. If we did this, Nintendo would cease to be Nintendo. It’s probably the correct decision in the sense that the moment we started to release games on smartphones, we’d make profits. However, I believe my responsibility is not to short-term profits, but to Nintendo’s mid- and long-term competitive strength” (Andriansang qtd. in Gilbert).

As it happens, the profits Iwata describes won out over Nintendo’s brand, which was subsequently reframed to include casual mobile games and gamers. Whereas consoles retail for hundreds of dollars, most people already own a mobile phone, and the abridged adaptations of main-series content of the kind we see in Heroes affords the ability to splinter content into digestible fragments playable on-the-go. Smartphone features like the push notification are strategically mobilized to incite players to check back frequently: “Fire Emblem Heroes: Your first summon is free!” is visible the instant a player turns on their phone the day new content is released. Moreover, unlike home console games, the collection of heroes in the mobile game are available wherever you are, whenever you want to peruse it.

Or is it?

Game Code: On Ownership and Ephemerality

The migration to mobile gaming brings with it new discursive frameworks of control. Digital piracy and the rampant trend of emulating video games have prompted Nintendo and Intelligent Systems to consider a model of game production wherein content is server-side, providing the developers with greater opportunities to regulate access. Players therefore have limited access over what is marketed as “their” collection. Within Heroes’ initial three months on the Google Play and Apple App stores, developers efficiently and effectively banned accounts with hacked or suspicious content, and foreclosed the possibility of emulation.

The result of Nintendo and Intelligent Systems’ control over the game code is the ephemerality of the digital collection. Whereas Amiibo or posable Figma figurines of characters exist as possessed by the owner until the plastic degrades or the owner resells or disposes of it, the digital collection of heroes exists insofar as Nintendo and Intelligent systems maintain the game and its servers. Since most gacha mobile games in North America were released between 2013 and the present, we currently have little ability to predict their lifespan, but the survival on the Japanese market has historically been a mere four to five years. [1]

Game Form: On the Capital of the Collect-Them-All Catchphrase

The term gacha, short for gachagacha, or gachapon, originated in Japan as an onomatopoeia for the practice of using toy capsule machines (Shibuya et al. 99-100). While Western freemium mobile games like Candy Crush, Farmville, and Clash of Clans encourage spending in order to progress through the game more quickly, gacha games are those in which one plays against their own impulses: the urge to exchange real-world currency to roll the dice for a randomly generated reward based off predetermined loot rarities, or the capacity to tolerate an imperfect collection.

The Wall of Gachapon at Akihabara. Photo from Wikimedia Commons.

The immediate success enjoyed by many of these games is predicated on their engagement with intellectual property that possesses a pre-existing and loyal fanbase: Final Fantasy: Brave Exvius, Star Wars: Galaxy of Heroes, and Star Trek Timelines are but some of the more well known and profitable games of its kind. In “The Non-Functional System, Or Subjective Discourse,” Jean Baudrillard notes the “the collector’s sublimity, then, derives not from the nature of the objects he collects […] but from his fanaticism” (3), and it is precisely this fan—with all that being a fan entails—who is the targeted consumer of these games. Still, the situation begs the question: if a player can make a one-time payment of $50 to purchase the latest Fire Emblem title for 3DS, gaining possession of not only the game card but all the playable heroes contained within, for what reason would they spend money on Heroes for a random chance at collecting the character?

In “Marvel and the Form of Motion Comics,” Darren Wershler and Kalervo A. Sinervo apply Joseph Schumpeter’s theory of creative destruction to Marvel motion comics, arguing that “in the very process of creating a new version of itself, its economic structure never ceases to destroy itself from within” (188). Heroes likewise trades on the cultural capital of its intellectual property to incite players to collect beloved characters yet again. Heroes acknowledges the existence of previous Fire Emblem titles insofar as they host recognizable characters—and can be another source of revenue in a bi-directional relationship to Heroes—but subsequently destroys the content by re-releasing characters with new artwork—often vastly improved from the low-resolution models of the Famicom and NES era—on a different platform.

Again, Baudrillard unwittingly offers insight on the monetization of collector psychology in gacha video games:

The object attains exceptional value only by virtue of its absence. This is not simply a matter of covetuousness. One cannot but wonder whether collections are in fact meant to be completed (6).

With the rate at which content is released in Heroes, it is clear that the collection is most certainly not meant to be completed, especially not for the free gamer or casual spender. Yet the desire to complete this collection, in line with the examples Baudrillard himself gives, incites the player to place exceptional and exponential value onto a collection of pixels on a mobile screen. As a F2P game a player does not even realistically own, these characters are quite literally worthless, but to a collector of these avatars, a given unit can easily end up costing upwards of $1,000 due to the game’s gambling mechanic and the interface that sustains it.

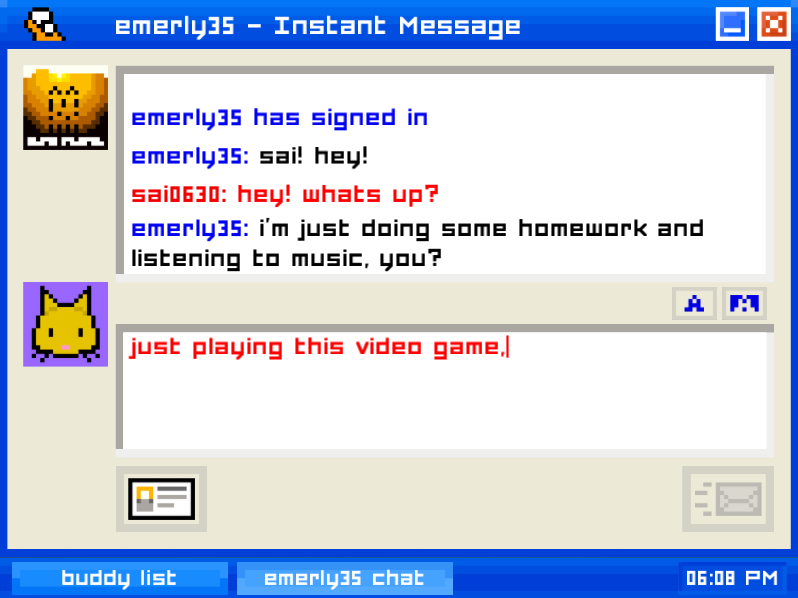

Interface: On Lack and the Intangible Collection

Although much can be said about the interface of a gacha game like Heroes, I wish to foreground the Catalog of Heroes. True to its name, the Catalog features icons of all the heroes a player has collected, interspersed with the shadows of the characters they have not. The catalog plays a specific incentivizing role in urging players to spend money to fill in the gaps.

[J]ust one object no longer suffices: the fulfillment of the project of possession always means a succession or even a complete series of objects. This is why owning absolutely any object is always so satisfying and so disappointing at the same time (Baudrillard 1).

The satisfaction a player feels when summoning a new hero—replete with exclamation mark—is offset by a glance at the empty boxes in the catalog. So why aim for the complete collection? One reason is nostalgia Walter Benjamin expounds on ownership as being “the most intimate relationship that once can have to objects” (67), noting that the possession of books and his tangible engagement with them evokes memories of the cities in which they were found or read or stored. In many ways, then, the collection is a narrativization of personal history, using objects as shorthand for life experience in which nostalgic meaning is inscribed. Players who have spent nearly thirty years invested in the Fire Emblem series will have cultivated relationships to the cast of over 800 characters (only 176 are presently included in Heroes), and these characters may serve as reminders of who the player was at the time of a given game’s initial release. It could therefore be no surprise that a collector wishes to complete the catalogue of characters imbued with personal meaning.[2]

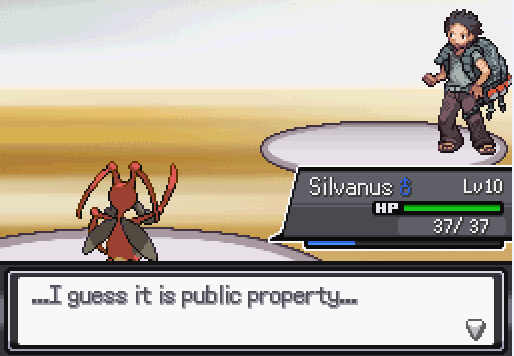

To the left, a screencap of the Catalog of Heroes. To the right, a screenshot of the primary interface players engage with.

Reception: On Ethics and Envy

While the length of this probe precludes me from fully exploring the phenomenon of collection in mobile games, there are two aspects related to reception that I wish to address, however incompletely. The first is the dubious ethics of producing a gacha game based on intellectual property historically marketed to young people. Much has been argued about the predatory practices of gacha games in general, but Fire Emblem Heroes in particular inculcates children into a highly addictive model for collecting their favorite characters.[3] The collection mechanic discussed above is strategically deployed to encourage users to make continued, large purchases with the release of new content even though the game can be enjoyed for free, and the sunk-cost fallacy is rhetorically deployed to maximize player retention and spending. The increasing ubiquity of the gacha game model necessitates critical consideration of how to protect at-risk individuals who, for love of a given IP, involve themselves in a predatory game, as well as what safeguards parents can put into place in order to protect their children. Who is responsible for educating players about the dangers of gambling? How do we reconcile “the problem of time [as] a fundamental aspect of collecting” (Baudrillard 9) with the ephemerality of the gacha game?

The final point I wish to make is with respect to the problematic ramifications of vilifying the gacha model, which include the dehumanization of people who actively and consentingly participate in it. A 2017 study of spending in F2P mobile games reports that 48% of F2P revenue is generated by a mere 0.19% of the playerbase (Allison 454). Both the industry and community boards such as Reddit and Gamepress refer to this fraction of players as whales. Just as Baudrillard notes that “collectors […] have something impoverished and inhuman about them” (17), players who invest in gacha mobile games are derided and dehumanized by players who have spent little to no money on the content, as can be seen through examples such as this meme by Reddit user MayorOfParadise or this graphic by MooseChangerPat, which declares that individuals who have spent between $1440-$2880 on the game “need to get a life.” Baudrillard notes:

at the terminal point of its regressive movement, the passion for objects ends up as pure jealousy. The joy of possession in its most profound form now derives from the value that objects can have for others and from the fact of depriving them thereof (11).

The vitriol with which high-spending players are received in gaming communities is therefore particularly fascinating in light of the fact that, unlike the collections Baudrillard and Benjamin describe, which foreground the uniqueness of each tangible object, the characters in Fire Emblem Heroes exist in near-infinite replication. The question thus becomes: how do we reframe and re-contextualize this argument when talking about digitally licensed content rather than a unique and priceless artefact, or is doing so impossible? How do we even qualify possession of something we cannot touch?

Recent announcements by Nintendo suggest that Fire Emblem Heroes is merely the beginning of the company’s foray into F2P mobile gaming and the profit margins they facilitate. As gacha games continue to be developed, harnessing the selling power of established intellectual property, these questions and those above merit further consideration in order to anticipate and understand the changing future of the industry.

Works Cited

Allison, Erik. “The High Cost of Free-to-Play Games: Consumer Protection in the New Digital Playground.”

Baudrillard, Jean. “The Non-Functional System, Or Subjective Discourse.” The System of Objects, translated by James Benedict. Verso, 1992, pp. 71-105.

Benjamin, Walter. “Unpacking My Library.” Illuminations, edited by Hannah Arendt. Schocken Books, 1968, pp.59-67.

Brian. “Fire Emblem Heroes Has Generated Over $100 Million so Far.” Nintendo Everything, 20 July 2017.

Fire Emblem Heroes. Intelligent Systems and Nintendo Entertainment Planning & Development. 2017.

Gainsbury, Sally M., Nerilee Hing, Paul H. Delfabbro, and Daniel L. King. “A Taxonomy of Gambling and Casino Games via Social Media and Online Technologies.” International Gambling Studies, vol. 14, no. 2, 2014, pp. 196-213, DOI: 10.1080/14459795.2014.890634. Accessed 7 Oct. 2017.

Gilbert, Ben. “The History Behind Nintendo’s Flip-Flop on Mobile Gaming.” Endgadget, 17 Mar. 2015. Accessed 8 Oct. 2017.

MayorOfParadise. “Whale BTW.” Reddit, 23 July 2017. Accessed 9 Oct. 2017.

Montford, Nick. “Combat in Context.” Game Studies, vol. 6, no.1, 2006. Accessed 27 Sept. 2017.

MooseChangerPat. “What Kind of Whale Are You?” Reddit, 20 June 2017. Accessed 9 Oct. 2017.

Shibuya, Akiko, Mizuha Teramoto, and Akiyo Shoun. “In-Game Purchases and Event Features of Mobile Social Games in Japan.” Transnational Contexts of Development History, Sociality, and Society of Play, edited by S. A. Lee and A. Pulos. Springer International Publishing, 2017, pp. 95-122.

Skrebels, Joe. “Nintendo Aims to Make 2-3 Movie Games a Year from Now On.” ING, 7 Feb. 2017. Accessed 9 Oct. 2017.

Wei Shi, Savannah, Mu Xia, and Yun Huang. “From Minnows to Whales: An Empirical Study of Purchase Behavior in Freemium Social Games.” International Journal of Electronic Commerce, vol. 20, no. 2, 2016, pp. 177-207. DOI: 10.1080/10864415.2016.1087820. Accessed 7 Oct. 2017.

Wershler, Darren and Kalervo A. Sinervo. “Marvel and the Form of Motion Comics.” Make Ours Marvel: Media Convergence and A Comics Universe, edited by Matt Yockey. University of Texas Press, 2017, pp. 187-206.

[1] In fairness, video games have gradually shifted from ownable, re-sellable media to microtransaction-based networked content over the last decade, ever since consoles gained the ability to connect to various developer stores via the internet. The increased prevalence of downloadable content (DLC) means that we have already had time to come to terms with the fact that our products now also rely on maintained services without which they offer merely incomplete collections. An example in keeping with the theme, Fire Emblem: Shadow Dragon, released in 2008, had an online shop through which, under certain conditions, players could purchase items unattainable through standard gameplay. When Nintendo terminated Wi-Fi services for the DS and the Wii in 2014, they consequently terminated the ability for players to access certain collectible classes and items. Players who wished to play the game after 2014 were thus required to come to terms with the impossibility of ever amassing a complete collection of items.

[2] One positive note about the interface of digital as opposed to physical collecting is arguably the more ecological approach to collecting. Physical media has clear financial and ecological costs: materials need to be purchased, extracted, and refined. The completed objects are transported to warehouses that move the stock to smaller storage facilities, that in turn distribute the merchandise to shops that pay rent and employ staff. With digital content, the labour of coding, illustrating, writing, and developing the game still exists, but the material costs are greatly reduced to that of electricity and bandwidth—presuming no one buys a smartphone solely to play Fire Emblem Heroes. Collections of character figures often results in a box of plastic collecting dust, and old consoles make their way to garage sales and sidewalks, so perhaps the redeeming factor of gacha collections is the reduced impact of the ephemeral collection.

[3] For empirical studies and analyses of the dangers of including gambling elements in mobile games, see Allison, Gainsbury et al., Shibuya et al., and Wei Shi et al.