The post An Interview with Nick Montfort appeared first on &.

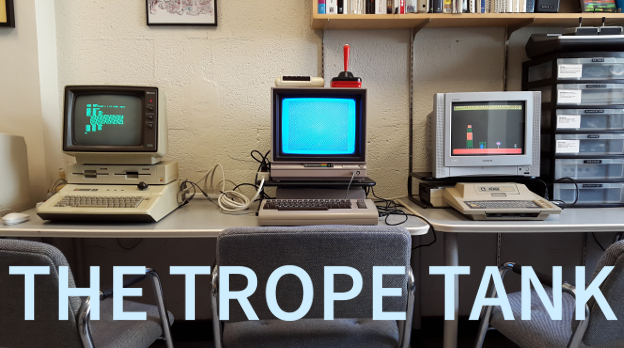

]]>Nick Montfort heads up the Trope Tank, a media lab at MIT, where he is also an associate professor specializing in digital media. He has authored several books, including Twisty Little Passages, a study of interactive fiction, and the upcoming Exploratory Programming for the Arts and Humanities. I had the opportunity to correspond with him about his work.

Thanks so much for agreeing to this interview. In your technical report about the Trope Tank, “Creative Material Computing in a Laboratory Context,” you wrote that “in reorganizing the space, [you] considered its primary purpose as a laboratory (rather than as a library or studio).” Your desire to distinguish the Trope Tank from libraries and studios strikes me as an interesting place to start thinking about what a media lab is—by first thinking about what it isn’t. Could you describe how the layout of the Trope Tank sets it apart from those other kinds of spaces?

Libraries are set up to allow people to read and consult collections, typically books but other sorts of media as well. Studios are for artmaking; classically they should have good natural light. Archives are for preserving unique documents, and direct sunlight is undesirable.

By explaining that we’re not an archive, I mean to stress that the materials we have are for use, not to be preserved for decades. The Trope Tank isn’t a library in that the main interactions are not similar to consulting books. And we aren’t mainly trying to produce artworks, either. There are aspects of these, but the main metaphor for us is that of a laboratory where people learn and experiment. So we have systems set up for people to use, not stored in an inaccessible way that will best preserve them. We aren’t worried with managing collections and circulation in the way a library is. It’s okay if the outcome of work in the Trope Tank is a paper rather than a new artwork.

At the same time our model is not a pure innovation — it is based on how labs work.

I’ve had some trouble understanding the concept of media labs. In your report, you effectively sum up my problem: “Humanists are familiar with libraries and their uses, artists know what studios are and some of the ways in which they are used, but a laboratory is not as familiar in the arts and humanities.” Unfortunately, you also state that this lack of familiarity “can, ultimately, only be addressed by doing laboratory-based work that leads to new humanistic insights and significant new artistic developments.”

I’ve never done lab-based work. Can you help me understand why “laboratory” is an appropriate classification for the Trope Tank? Might “workshop,” with its multiple meanings (it’s a space for working with technology and also a collaborative activity with intellectual, creative, and/or practical components), serve even better?

Workshops are mainly for making or repairing things; laboratories are for inquiry, but that includes conducting inquiry in a practical way that can involve making.

I’m interested in the dilemma you present: the incommunicable quality of lab work. It reminds me of something Matt Ratto said about how critical making communicates concepts to the body, not just the brain. That material, tactile, experiential aspect strikes me as a fundamental difference between lab work and conventional humanities scholarship. What is your take on that?

There are aspects of traditional humanities scholarship, such as that in the material history of the text, also called book history, which are quite similar to our lab-like approach. With regard to this type of work in the humanities, we’re also learning from a tradition rather than developing an entirely new idea.

What are some of the things, whether tangible or intangible, that the Trope Tank produces?

The Trope Tank is for producing new insights. It isn’t about production in an industrial or consumer sense, or for that matter even mainly in an artistic sense.

In connection with my first question, could you tell me how the insights produced in the Trope Tank differ from those which more traditional humanities scholars might produce in a library and also how the media lab’s creative output compares with what one would expect to come out of a studio?

I think one of the answers is in how our projects sometimes lie outside of standard scholarship or standard artistic production. The Renderings project is a good example of this. We’ve translated and in some cases ported or emulated digital poetry from other languages. Most conventional literary translators have no idea what to make of this literary translation project. It involves study of and reference to earlier projects to translate electronic literature and constrained and avant-garde writing. The result is not well-understood (in the visual art world certainly) as artistic production, though.

In other cases we have studied digital media and art in ways that cut across platforms (the Apple //e) instead of confining themselves to standard categories of videogame, literary work, etc. This makes new connections between quite obviously related digital works that have never been considered alongside each other before.

Could you tell me what a typical day at the Trope Tank looks like? Who uses the space on a daily basis and in what capacity? What is it like for you to work in that space?

I don’t think there are typical days. We host class visits at times, have discussions with visiting artists and researchers at times, engage with software and hardware in quite specific and directed ways at times, and use systems in a more exploratory way at times. We have meetings with larger or smaller numbers of people or work individually. Often the people involved in the Trope Tank work from other places, if they don’t need the material resources of the lab. The Trope Tank isn’t an assembly line or Amazon warehouse in which the same activity happens all the time.

Having very fond memories of playing Infocom games (the Zork and Enchanter trilogies) on my father’s Apple IIe, I was a bit startled to learn that the Trope Tank hosts a community which is still developing the interactive fiction genre. In retrospect, it seems obvious that so much of the genre’s potential was never explored back in the 80’s. Why the enduring interest? What is the relevance of this sort of work in the context of contemporary literary production and game design?

The question of why interactive fiction is still interesting deserves a book-length answer (Twisty Little Passages, Nick Montfort, MIT Press, 2003) or a documentary film-length answer (Get Lamp, Jason Scott, 2010). The main way interactive fiction relates to contemporary literary production and game design is that it is contemporary literary production and game design. Beyond that, it’s not simple to say how interactive fiction, still being made in very compelling ways, relates to other forms of literature and game. You would do well to consider specific works of interactive fiction and specific people, and how they relate to other sorts of literature and gaming.

Your book is on my holiday reading list, and I’ll see if I can track down that documentary. Thanks for that.

The book is a bit antiquated by now — no coverage of Twine and today’s popular (and sometimes radical) hypertext interactive fictions, for instance. But, I hope it’s still worthwhile.

Your upcoming book is intended to teach basic coding skills to workers in the arts and humanities. What inspired you to take on this project? Who will benefit from it most? More importantly, how can I, an aspiring fiction writer, benefit?

The book was mainly motivated by particular people in the arts and humanities who are interested in programming but who have not been finding the support to learn about it. I also saw that there was little high-level interest (in writing about the digital humanities, in curriculum committees, etc.) in teaching programming — even though millions of people learned how to program just for fun in the 1980s. Exploratory programming is about learning and discovery, not about instrumental uses. So, I would suggest that you and others in the literary arts can benefit by understanding powerful new ways to think and to amplify your thoughts using computation.

Thank you for taking the time to correspond with me.

The post An Interview with Nick Montfort appeared first on &.

]]>The post Bedroom as Beadwork Lab?: An interview with Cedar-Eve Peters appeared first on &.

]]>Cedar-Eve Peters is an Anishnaabae visual artist and beader from the Ojibwa nation, currently based in Montreal. Cedar sat down with me to discuss the nature of her workspace and its relationship to her beading practice. We also grappled with a question previously asked on the dhtoph blog: “do we really need a designated space for work that we can just as easily do at home or our favorite coffee house?”

The transcription has been edited for clarity.

So how would you describe your lab space?

Very messy. Like right now it’s very disorganized.

Could you talk about where it’s located?

Oh yeah. My workspace is also my bedroom, so sometimes that’s annoying because I can’t separate workspace from sleep space. I guess it’s kind of organized. Everything’s in containers at least, but it just seems like things are all over the place right now.

What would you say the workspace itself consists of?

Mm…beads? You mean the materials?

Not so much the materials but the things your going to use. Like this chair, and that desk, the way it folds down, the cutting mat and the loom, your boxes of beads; these are all things that you need to get this work done.

Yeah. I guess I don’t think about that. Containers and shelves. Mostly containers I guess. A bunch of lights.

A surface?

Not so much right now. [laughs]

Surface space must be essential being that you need to be able to see all these tiny beads.

Yeah, if the surface isn’t clean then I feel like I can’t think straight, so that’s annoying. But also, it helps in a way cuz I’m just like, stimulated by everything thats around.

Is that a positive to working in your bedroom?

No. [laughs] I don’t think so.

What are the core practices you’ve established to create your beaded work?

Like my routine?

Yeah.

I guess I’ll wake up, depending. Usually early like 8…I guess that’s not that early for most people but, from a person that used to wake up at 1PM everyday to now 8AM…

I’ll bead for like an hour or two, and then watch tv and have breakfast, and then do whatever I need to do, and then maybe sit down again around like 2 o’clock and start beading until like 5 or 6, or whenever I’m hungry again. So basically hungers the only thing that takes me away from it. But I try to wake up every morning and start something cuz I feel like if I don’t do it then, then I won’t do it at all.

Do you have to do any set up when you start something in the morning?

Well if like it’s messy like right now, I wouldn’t start. I really wanna clean that desk right now, put shit away. But yeah, I guess the only thing would be that I try to clear it off at the beginning of every new item, because if there’s like stray beads laying around, I don’t know, it bothers me. I have these set little piles and I wanna completely deplete each little pile before I move on to something else. Or I just put it in a bag and then thats when like the miscellaneous pieces [are made].

It occurs to me that you don’t have to like pack everything up at the the end of the night and then unpack; because you’re the only one using the space you can leave things out and then come back to them.

Yeah.

I imagine that is a big time-saver.

Yeah and even if I do finish something—like right now, I finished a pair of earrings but I haven’t cleared off the leather mat with the beads on it yet cuz, I dont know, I was just like, I’m tired and I cant be bothered to do this, so.

If you’re not beading in this designated space that you’ve created, where else does your beading take place?

If I’m at my mom’s house I bead in the living room cuz the table in the living room, its right beside a huge window, which is like the width of the wall. Theres a lot of natural sunlight, so I like beading there, and it’s amongst plants and stuff, which is cute. But when I’m doing the workshops and stuff that’s usually in the lounge of the Aboriginal Student Resource Centre at Concordia, so there it’s a bit different because there’s people coming and going.

Something I’m dealing with is that when I’m at home it’s solitary and it’s just my energy alone, you know, and a lot of the time I’ll just sit in silence and bead, like I wont listen to anything. But when i’m at Concordia it’s like all these students are passing through, getting a snack or printing off whatever. They’ll stop and chat but it’s obviously like I cant focus my whole attention on making a pair of earrings in one sitting, where I would do it here [in my bedroom]. I also find it kind of distracting cuz like, I don’t know, it’s not like these people are bad or anything it’s just like all these different energies are passing and I feel it affects my concentration and my ability to complete something when I’m amongst other people. I have to be alone to complete the project I guess.

So do you have different routines for different spaces? Or is it pretty much the same?

I guess pretty much the same. Cuz when I was in the mukluk workshop a lot of the people there were already beaders, so that’s different because everyone’s so focussed on making their own thing. There’s some chatting but for the most part everyone’s silent and, you know, focussed on their own project, but when I’m teaching workshops it’s like everyone’s always talking. Like, theres focus but not as much focus—like trying to learn but full attention isn’t on learning? If that makes sense.

Why do you think that is?

I think for people to pick up beading for the first time is really intimidating and I think people think that they’re capable of making something really clean, and neat, and tight-looking on the first try when thats not the case. It is a solitary thing so I think when you’re in a workshop doing something you’re already familiar with it’s just easier. You’re more comfortable to just dive right in I guess, whereas if you’re coming as a first time learner, and I’m teaching too, like it’s new to me as well.

So this might sound kind of like a silly obvious question but, just to articulate it once and for all, what is produced in your beading space?

Earrings, chokers, and bracelets mostly. Recently made that little pouch with beadwork on it and I wanna make more of those, but yeah, mostly jewellery. It’s also that time of the year for people wanting gifts and stuff, so its a lot faster for me to turn out jewellery than these little pouches.

And you sell those for income, that’s your primary income?

Yeah.

So your beading space is where you accomplish your living, basically.

Yeah…which bothers me sometimes because I would want a studio space, but when I had the studio space I hardly made the effort to go. Every time I was there I would feel more pressure, because it would take me so long to get there that I would be like, ‘I have to stay for like at least four hours’, and if I didn’t then I would feel like I wasn’t like utilizing it, like I was wasting my money. I’m more productive at home cuz I just roll out of bed and do it, and take naps and stuff in between.

So would you consider your current beading space adequate?

Yes.

You don’t have any functional issues?

Maybe I’d want more shelving or something just cuz I have a lot of knick knacks. But yeah it’s pretty functional, there’s like access to most things so [I] just need to organize it a bit better. But yeah. Shelves, yes.

If you could make any changes, what would they be? Maybe in addition to the shelves?

Probably not have it in my bedroom. Like, if I had enough money I would just pay for the middle room [of this apartment] and have my studio in there, and have this as my bedroom. That’s pretty much it. I still like working from home, so I guess the ideal situation would be to have a studio in my apartment.

Do you think that is achievable, realistically, either now or sometime in the near future?

Yes. Cause I gotta be positive about making that money!

The only thing that would really hold me back is that I wanna travel, so when I think about paying (if i’m lucky) like $200 a month for a studio space—maybe sharing it with someone else or whatever—that’s $200 I could save towards travelling which I feel right now is more important cuz like I’m still being productive when I’m in my room. I think that’s the only thing thats really holding me back.

But then again I’m like, if I did have a studio space, since this is my job, my full-time job, it would just kind of pay for itself anyway, cuz I’d be making so many things and maybe I could have studio visits so people could come and buy things, like once a month or something.

Having a separate space brings new possibilities?

Yeah cuz I don’t really feel comfortable with people coming over to buy things unless I know them as a friend, you know. I’d rather just meet someone at a random cafe, but then that feels weird too, like using another space to like sell things. It’s not like I’m setting up shop so to speak but like…

It’s just a hand off?

Yeah.

The space where you sell things is primarily online, right?

Yeah and at shows, like local markets and stuff. But yeah mostly online, and I think Concordia’s [weekly] farmers market’s been helping because thats more steady.

So your retail space is always shifting?

Yeah.

We should also talk about how you’re self taught, and so in that way your lab space is also where you learn new skills—would you say that? Still?

Yeah…yeah. Yeah, [laughs] I would say that. Because I feel like when I’m inspired to do something I have to do it right then and there, I don’t have time to waste in between. When I had that studio, if I was taking the subway it would take me like half an hour to get there. If I was biking it’d be like, fifteen minutes, or twenty, but it’s all uphill so its still annoying. Whereas here I’m like, “Oh, I feel creative. I’ll just like sit down and do that now.” Cuz it’s like by the time I hit the studio, I don’t feel that urge as much.

Lost momentum?

Mmhm. And the idea is gone.

The post Bedroom as Beadwork Lab?: An interview with Cedar-Eve Peters appeared first on &.

]]>The post Electronics & Artistic Production: Interview with the lab coordinator of Eastern Bloc appeared first on &.

]]>Eastern Bloc is an artist-run centre and media lab in Montreal. Since 2007, it has been exploring and pushing the boundaries of the intersections between art, science, and technology. By facilitating hands-on workshops, the centre sets itself apart from commercial galleries insofar as it not only exhibits digital and new media artworks, but helps to educate and provide resources for their production.

The lab’s mandate states that it “provides a platform for experimentation, education and critical thought in practices informed by hybrid, interactive, networked and process-driven approaches.” This includes a mandate to offer a shared lab space involving tools and resources for electronic and digital/new media art. Operating such a lab includes offering technical support, engaging with the community, and reaching out to people who are interested in the artistic use of technology, but may be without the means of producing it. Ideally, this is all in the service of the democratization of technology in a time when we are increasingly alienated from it, despite its prevalence.

I spoke to the Lab Coordinator, Martin Rodriguez, in order to get a better sense of what happens here.

What, if anything, would you say you produce? Is there something material that comes out of this lab, or is it something more intangible, like “knowledge”?

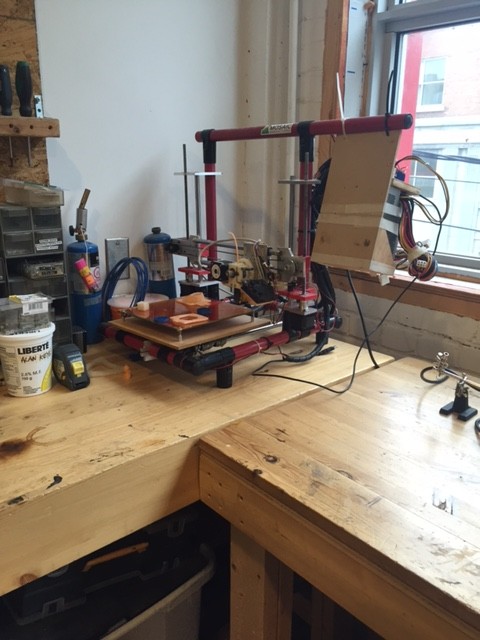

There’s a lot of music synthesizers that are being produced here. That’s one of the main things. There’s a lot of audio works that are happening in our lab right now. We can do everything from fabricating the PCB board, which is like the electronics aspect of it, like just the circuit so you can do multiples. We can make all the casings for them, so there’s the CNC machine which would allow you to cut the wood. Hopefully we will be able to cut aluminum with that.

We also have various different types of woodshop tools. We have a 3D printer there, which we just got up and running. That will allow artists to design 3D objects that are more complicated, something that you couldn’t do with a regular wood and milling machine.

Our lab is really geared toward the creation of electronics projects. What I mean by that is we don’t really have a lot of computers in here, it’s not really made for people to be programming software. So we have all the materials you would need for soldering, and different types of wires. Stranded wire and solid wire, different components, different resistors and capacitors.

Do you think a large part of what you do is educating people on how to use these materials? Or is it more of a resource for artists who already have the knowledge to have access to equipment?

The way our lab functions is a little bit of both. We have lab members who pay a fee to have access to the lab 24 hours a day. They often bring a lot of their own equipment because this is just standard stuff. We also offer workshops, which is a way of generating income for ourselves. But it’s also a way for us to talk to the community. I think a lot of the workshops here are getting people to feel comfortable, and understanding what media and electronic art is. So a lot of our workshops will be like intro to arduinos, or introductions to MaxMSP, Pure Data, or Python. And we also have other workshops which are more like, how to do VHS glitch art. We’ve had workshops that are more panel-based, discussions around artists and their processes.

How do you choose who does the workshops? Do you have artists come in or is it the staff that hosts them?

Because the lab is attached to Eastern Bloc, which is an artist-run centre, we have a mandate to support emerging artists so we offer workshops that are given or facilitated by emerging artists. Oftentimes we find that is more engaging or interesting. Because Youtube is such a powerful thing right now, people can find videos and find out how to build a lot of stuff there, but what’s interesting is coming here and being with an artist and finding out what their whole process is.

What is the relationship of the gallery to the lab? Are their projects similarly aligned? Do you integrate the workshop element into the exhibitions?

Yeah, that’s one thing I’ve been trying to pull in recently with the lab. When we have an artist who comes and presents something to also present a workshop. In the summer, an artist called MSHR came and presented here, and after their presentation we tied in a DIY synth workshop. We had these biopolitics exhibits that happened during Fall with workshops tied in. We also have an artist residency program, where an artist will have full access to the laboratory for 2-3 months, and at the end of that they’ll present what they’ve built during that period.

What are your feelings on the space itself? What is its story, and how does it shape the lab?

We’re currently in the process of acquiring more space for the lab. It’s quite small as you can see, it’s under 500 sq feet. So we wanted to switch it over to where the offices are. Right now there are only two of us working, but with interns we can get up to about 5-7 people in the office. The lab needs to be bigger, there are more demands and we need more tools.

A bigger space would allow us to have more machines. If you go to some of the FabLabs, like FabLab du PEC, which is in Hochelega, they have a much bigger space and a lot of interesting tools. Two different types of 3D printers, a laser cutter, a vinyl cutter, a CNC machine. It’s just a massive space. But it’s different, they don’t have a lot these electronics things. We are kind of limited by the space that we have, it’s not easy to create large pieces because there is not a lot of elbow room.

What are the open lab nights like?

Yeah, we’ve been doing the open lab nights, they’ve been running. But as of recently we’ve switched the programming because it was so open that no one came. It was just like, “hey it’s an open lab night come and check it out.” People would just not show up. So I was like, this isn’t working, we need to find a different model. So what I started doing was trying to create themes so we could target specific people. Right now the open lab night we’re having is a sound lab night. I’m hoping we can do something like a programming one, or now that the 3D printer is running we can do a 3D printing lab night.

Is the idea for open lab nights that you can bring people in who aren’t familiar?

Yeah, to bring people in who aren’t familiar, but also to grow a community. With the sound lab night there are a lot of people in Montreal that are fabricating sound, or experimenting with instruments. So we’re trying to create a community around that. And an exchange of ideas, of circuits, of concepts.

Why ‘lab’? What about this space makes it a laboratory, or just, what comes to mind when you hear this word?

Outside of this context when I hear ‘laboratory’ I think of beakers. But I think the larger concept behind it is like, experimentation, and developing something to be accurate and fully functioning. I think that is a lot of what happens here. Maybe the word ‘lab’ has been used so much it’s getting played out, and that’s why people have a bad feeling against the word, its overuse—

Oh, not a bad feeling. But it has certain connotations. Experimentation, a collaborative space where people have to work on ideas together. It’s different than a factory or something where you know exactly what is being produced. It’s kind of indeterminate in that way. I think that’s why people feel compelled to call their space a lab.

Yeah definitely, I think so. I think sometimes the startup scene tries to take those types of words, those buzzwords and make it something. I feel like what we have in spaces like these feels more like a lab, like what we know as a science lab, because of the machines and what is produced and experimented with.

The post Electronics & Artistic Production: Interview with the lab coordinator of Eastern Bloc appeared first on &.

]]>The post A Look Inside: The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries Digital Humanities Lab appeared first on &.

]]>In my search for people who work/study/use or interact with physical spaces in the Humanities as part of the “What is a Media Lab?” project, I had the opportunity to speak to Ann Hanlon of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries Digital Humanities Lab. The DH Lab was an intiative launched in the Fall of 2013 as part of a collaboration between the UW-Milwaukee Libraries, the Center for Instructional and Professional Development (CIPD) and the College of Letters and Science as an interdisciplinary collaborative space within the library. Ann Hanlon, Head of the Library’s Digital Collections and Initiatives, was kind enough to answer all of my questions about the project and gave me a discursive tour of their space.

1. What does the Digital Humanities Lab look like?

What spaces, both physical and virtual, are available for members to use? Are there any particular objects or tools associated with these spaces?

The DH Lab is located on the second floor of UW-Milwaukee’s Golda Meir Library, the main (and only) library for the UWM campus. The space was formerly a computer lab, and then quiet study space. It is surrounded on two sides by floor-to-ceiling windows, and on a third side by glass walls that look out on the Music Library and a collection of childrens books. The fourth wall is a temporary wall that is bolted shut. The space is large, and includes seven round tables that seat four to five people each. There is a podium and several other tables and chairs, and one large HD monitor (55″) for presentations. There is no other dedicated computer equipment in the room.

We are developing a virtual sandbox for the Lab. This is based on CUNY’s DH in a Box project. We hope to expand on their code to build a virtual lab, essentially, so that our patrons could access DH tools like Omeka and Mallet for workshops, and eventually, classroom projects, from anywhere. Ideally, patrons would come together in the Lab to learn to use these tools.

2. How are the spaces of the Digital Humanities Lab used?

Is the use of lab space structured? How is knowledge produced in the lab? Does it have any material aspects?

The Lab is loosely structured, and this has been one of its chief benefits. Despite our lack of equipment, faculty, staff and students regularly use the Lab for scheduled meetings and presentations and panels. The Lab has been most useful as a space for informal presentations, meetings, and brown bags. Knowledge is produced through discussion and collaboration, and bringing together people who otherwise might not work together — faculty and staff, and students, from departments across campus.

The space is really primary right now, as opposed to any research projects or class projects that are coming out of the lab right now. We did have one collaborative project with a community partner, called “Stitching History from the Holocaust.” In partnership with the Jewish Museum of Milwaukee, we created a digital exhibit in collaboration with their physical exhibit. The physical exhibit received a lot of press from outside the university, which led to an increase in our own funding for the project.

Right now, we’re focusing on building events for the space: designing workshops and providing infrastructure. We’re still building up the skill-sets: staff, physical infrastructure. These skill-sets include data management and repositories, like Omeka (an open-source exhibit software from the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media at George-Mason University).

How does the space work differently from other library spaces?

It’s a closed space, which surprisingly makes it more flexible in terms of use. It’s a more formal “open-but-closed” space. It isn’t used for classes, but rather meetings and events around digital humanities.

3. How is the Digital Humanities Lab structured?

Who are the organizers and users of the lab? Where is the Lab situated in relation to the university’s infrastructure? Is the Digital Humanities Lab associated with any university research groups or projects?

The Lab is organized primarily by the Library. It has one Coordinator (me), and recently an Advisory Board was assembled and charged with oversight of programming and long-term planning by the Provost. The Advisory Board is chaired by a faculty person from the History department, and includes faculty from English, the School of the Arts, the School of Architecture and Urban Planning, the School of Information Studies, and the Libraries, as well as a graduate student (History). The Lab is a hybrid, perhaps, in relation to the University’s infrastructure. It is likely best recognized as part of the Library, but has strong relationships with several university research groups on campus, including the Center for 21st Century Studies, the Social Science of Information Research Group, the Community Engaged Scholars Network, and the Digital Arts and Culture certificate program.

Would you be interested in working with other DH Labs?

Yes! We’ve worked with other research groups on campus to “pool cash” to bring in scholars from other universities. Generally in the form of panels, like one we had in February on critical data history.

4. What is your role in the Digital Humanities Lab?

How did you become associated with the project?

I am the Head of the Library’s Department of Digital Collections and Initiatives. I became involved with the Lab through our Strategic Planning process, where I proposed the Library should lead regarding DH. In connection with that part of the plan, I helped convene a group of faculty who we knew were active participants in the campus’s Digital Futures initiative, and asked them what they saw as the Library’s role. The faculty proposed the Library as the logical home for DH, and that space was one of the key components to raising visibility and fostering DH research and project development. Through that meeting, I worked with another staff person from a related department to begin designing the space, but more actively, begin developing programming and workshops for the Lab, and planning for future infrastructure — including technical as well as administrative.

Editor’s note: The UWM Digital Futures initiative was part of the university’s strategic initiatives plans for teaching and research. The initiative was meant as a yearlong conversation on emerging technologies and their impact on the university. In 2010, three focus groups (Teaching and Learning, Research, and University Operations and Services) were asked by Johannes Britz, Interim Provost and Vice Chancellor for Academic Affairs to consider the opportunities and challenges of new technologies and digitally enabled processes and recommend action steps for UWM. The key issues the initiative addressed were: the adaptability of the organization in adjusting to technological innovation, ethical issues related to new technologies, best practices in utilizing new technologies in administration, the impact of digitization on how we conduct research, and the rapid pace of change in instructional delivery (including developments in online and blended instruction, the ‘consumerization’ of the learning experience, the development of personalized learning systems, and the increasing use of simulation technologies). While the Digital Futures initiative predated the interviewee’s involvement with the project, I asked her about how the initiative shaped the Lab’s development.

It’s had an impact on how we wrote the library strategic plan in 2012/13 and contextualizing the DH Lab (which was a product of the Digital Futures initiative) through the working group’s recommendations around teaching and research.

We’ve had a lot of support from the faculty for this lab and they’ve been extremely tolerant of the establishment of this lab. We provide the space and the skill-sets and the technical infrastructure, and we’re looking at the rest of the university for skills to share and incorporate for more peer-to-peer formations.

6. What are your impressions of the Digital Humanities Lab’s use of space?

Can you imagine ways the space could be changed or improved? How would that affect your group’s research practices or knowledge production?

I can imagine the space taking on more useful equipment for collaborative work, but not becoming crowded with permanent machines. The space is often empty, and my greatest hope is that we’ll secure funding for permanent staff to operate services out of the Lab. This would also include retraining our Library staff to offer their expertise in related areas via the Lab on a regular basis. The main effect additional hours, staff, and equipment might have on knowledge production might be an increase in integration of DH tools and methods in undergraduate and graduate classes, which would in turn, I believe, lead to more robust faculty research and possibly, grant-funded projects. However, classroom integration is likely the biggest beneficiary of any additional development of the space.

7. Has working with the Digital Humanities Lab changed your own thoughts on how space is used in humanities research?

Yes — it has made it clear to me how important space itself is. That has been the rallying cry for our own DH Lab. It’s a modest space, but it’s very existence has increased visibility for DH on campus and brought together faculty and staff from across departments to identify under the single banner of DH and to imagine projects and initiatives that would otherwise have been bottled up in individual departments. The space has served a sort of “stone soup” purpose, in that we provided the space, and everyone else has brought their skills, networks, projects, and questions to the Lab to help form what it is today, and what we hope it will become.

The post A Look Inside: The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries Digital Humanities Lab appeared first on &.

]]>The post Workshop Facilitation and Transient ‘Space’: An Interview appeared first on &.

]]>When my initial interviewee (someone with a large amount of involvement and a fairly high position in anti-oppression education) had to back out part way through, my immediate reaction was to panic. Then, I remembered that, actually, even if they didn’t have particular titles, there were many people around me who had been engaged in this type of work and who had interacted with the transient ‘space’ of the workshop many times over. Luckily enough, one of these friends was kind enough to sit down with me and talk about it.

Ffionn M: As I’ve mentioned, the general theme of these interview assignments is “the lab” or spaces of knowledge production. When we got the assignment, my interest was immediately pulled in the direction of ‘spaces’ that were a little more fluid, knowledge productions that occupied a physical ‘space’ for only a short period but also transformed it into a very distinct sort of space of its own. That’s why I’ve asked you to come talk to me about — broadly defined, here, as ‘social justice’ — workshop and discussion facilitation.

To start, I was wondering if you could talk a little bit about your experiences facilitating workshops (what organizations, what sorts of workshops, where they were held, what led you to become a facilitator, etc.).

Theo K: Well, I first started getting involved with Queer McGill after being elected as one of the communications admins. I ended up getting very involved with Queer Concordia, the Union for Gender Empowerment at McGill, and the Centre for Gender Advocacy at Concordia as part of my communications officer duties. That was when I started getting into facilitating groups and leading discussions in general. Especially after my transition and becoming one of the only trans admins on the QM board, I was trained in Trans 101 workshops with the UGE that I facilitated for QM workshop events as well as admin safe space training programs. I ran the Trans 101 for safe space training for QC executives and volunteers as well. I also facilitated for discussion groups fairly often. Most of these were usually held in the QM office or the SSMU(mcgill student union) building’s bookable meeting spaces, or the QC office- usually spaces on campus run by students. Later on, after I’d stepped off the QM board and became more involved with the CGA, I volunteered to be trained as a facilitator for plans made by Concordia to have mandatory consent workshops in the first year residences; these plans ultimately fell through, and we were deployed to facilitate smaller workshops at Concordia’s Arts and Science frosh. I also became a facilitator for Trans Concordia for a brief period, facilitating discussion groups in the CGA meeting space generously lent to us.

FM: You mention that you were trained to facilitate Trans 101 workshops after you transitioned and became one of the only trans administrators on the Queer McGill Board of Directors. It sounds as though the responsibility fell on you because you were trans. Did it feel like that? Did that affect the way you were able to facilitate Trans 101 workshops in that space?

From your description, it also seems like this was the first type of workshop you were trained to facilitate. How do you think your own experience (personal knowledge) related to you being trained in this sort of facilitation? When you were learning to facilitate and later when you were facilitating these workshops, what sorts of knowledges do you feel you were bringing to the table and engaging with?

TK: Yes and no; Queer McGill, and a lot of queer campus resources that were student-run tend to have a bad rep in terms of being trans-friendly because of the fact that they tend to lean more towards social events, like parties. I took it upon myself when I transitioned to facilitate the workshops, since I felt that I was the only one with the depth of personal knowledge to do it, but in hindsight, I feel as though I was expected to do just that. I suppose that’s just the way it goes; people always expect the one who would benefit most from an endeavor of spreading knowledge to be the one to work hardest at doing so. Also on the flipside, being the only trans admin also gave me a sense of authority when facilitating workshops, of course. There’s a certain sort of understanding that if you’re a cis person coming to a trans 101, you’re not going to know better than the trans guy running it.

Being trans doesn’t mean that you’d know everything there is to know about trans politics, though (believe me, there are many trans folks who are still quite unaware). Of course I would have to have had training, and being involved in the construction of the actual workshop was quite enlightening as well- I was part of revamping the trans 101 that the UGE has, and I learned a lot about gender politics during that. I guess I think that being trans simply helped me make more sense of it, or gave me a perspective that is capable of a deeper understanding of gender politics than those who don’t have to live the complications of it. Improvising during a facilitation to counter questions or disagreements is also a skill that facilitators are trained in, and that deeper understanding helps immensely.

FM: I think that’s an interesting tension — that because you belong to the marginalized group, you are expected to be the bearer of knowledge but, at the same time, in certain ‘spaces,’ it also grants you a level of authority. Were there any times where you felt these two forces come into conflict in a facilitation space (or in life in general, since these ideas tend to continue outside of workshop spaces as well)?

You also mention the importance of being able to improvise during a workshop. I was wondering if you could talk a little bit more about this — how it comes up, how your deeper understanding of particular issues helps, what ideas those participators are bringing to the table and what it all results in.

TK: There’s never really a conflict so much as the two conflating to become taxing situations. Of course there’s the incidents that all trans people (and all marginalized people, for their respective marginalizations, for that matter) are weary of- cis people simply expecting to be educated, though they may even be resistant to this knowledge, and assuming that their journey to enlightenment is our responsibility. I usually come to workshops with the energy and expectation to deal with this, but the worst I guess is when it happens outside of workshops, in my daily life, or in my personal internet presence on social media or some such. I don’t think many people actually understand the mental labour that goes into coaxing someone to understand something new. Of course, sometimes I’m deemed too close to the issue to really be objective about it, and my authority on the matter is undermined that way- it’s a bit of a paradox. Usually employed by people who have no intention of understanding, but rather proving to themselves that they tried and that they were ultimately right.

In terms of improvising, there are always questions that ask for things not covered in the workshop. Usually I try to share a consensus with my fellow facilitators if I have any, about whether we could go over the question, or it would open up a discussion much more advanced than a 101 and that we need to skip for time concerns. Having a deeper understanding of the material helps us decide these things, or improvise ways of answering exactly what the person attending may be confused about in a short amount of time.

FM: I hear that! I have definitely, in my own experience with facilitation, noticed that there is a huge difference in the types of dialogues that are produced when you have folks who want to be better about an issue and folks who think that they’re already in the right. It’s also almost always (in my experience) the latter who expect you to educate them outside of the workshop space, at their whim — I think, maybe, those attitudes go hand-in-hand.

It’s interesting to think about this sort of participator in terms of the ‘space’ concept I mentioned at the beginning, though, as well. Maybe the lack of distinct physical space for workshops gives this type of participator the (incredibly misinformed) idea that any encounter with a marginalized person or an educator of this type is, itself, a site for facilitation? Further, what other effects do you think the temporary quality of physical spaces might have on workshop environments or how workshops and discussions are conducted?

TK: Well, the part where people just seem to expect education from marginalized people comes from a fundamental lack of empathy, in my opinion. I usually attribute it to a kind of ‘mental space’: everyone makes different mental spaces for different encounters. When with a friend, you’d make a mental space of friendliness or familiarity, or when dealing with an acquaintance you’d make a mental space of politeness or distance: I’ve found that a lot of cis or white people have treated me as if I’m some sort of kiosk (laugh). I think that there’s some sort of part where who I am (queer, poc) compromises any mental state that they would make while talking to me.

It’s actually something I’ve found because workshop spaces have such a transient nature to them- it’s usually a club office, or a rented meeting space at a restaurant/cafe. There are no assigned places for workshops the way there are for lectures or meetings, so the actual workshop space is a sort of… collective mental one that you join in on when you enter a workshop. The facilitators set the rules and boundaries for the meeting at the start of the session, and these rules hold until the end; I’m not entirely decided yet on whether or not this has a positive or negative effect on the workshop experience and endeavor in general. On one hand, the construction of the mental space makes for attendees that are more engaged and remember more; on the other, it might take away from the perceived legitimacy of the session, and consequently, the information presented in the session. I’ve found that it helps bring a more casual air to workshops, where people feel comfortable asking questions but also understand the deeply personal nature of some of the politics that are being discussed.

FM: I think a mind ‘space’ is exactly what it is. And this creation of ‘workshop’ environment in terms of the written and unwritten rules of behaviour is exactly what changes the physical space into a workshop or discussion space for a short time. How have these mind spaces met with the physical spaces in the past? Have there been particularly fruitful meetings of environment/space? have there ever been particularly poor spaces? Have the physical spaces or what might have been going on around the workshop ever ‘intruded,’ so to speak, on the workshop? If so, what was the result?

TK: I mean, spaces that can be closed off from the general public are always better. There have always been smaller interruptions, especially when the space is one that’s usually used for something else: club rooms always have someone or another coming by for something, and the SSMU general space in particular always has other students and other clubs making noise. A common interruption is when someone steps into a club room, unaware that it’s a workshop space at the moment, and the facilitators end up having to explain to them what’s going on; they either stay or leave, but the bewilderedness of finding the space reappropriated to something they weren’t expecting is still present. That’s essentially what workshops have been like for me so far- reappropriating a physical space with a mind space. The problem is when using an open space that other people already have a mental space of before the workshop space is constructed.

I remember a safe space training workshop that was held in the SSMU general; I wasn’t facilitating, but I was familiar with the material and the facilitators. We were seated around a table at the far end of the space, when somebody else, a tall white dude sat at the table and interrupted to ask what was happening. The facilitators had to re-draw the rules and boundaries for the newcomer, a bit sloppily because of time constraints, and I could feel a shift in the space to a palpably uncomfortable one that was particularly difficult for the facilitators. He kept asking questions about things that had been covered before he had arrived and taking up more time and space. The mind space of the workshop had been compromised, even though the workshop was open to everyone, this sudden interruption made the facilitators lose grasp over the space somewhat.

I’ve always enjoyed the workshops and discussions I’ve facilitated in the more closed spaces for this reason, I suppose. When I was working with the Concordia groups more extensively later on, the CGA lent us a room to use, that was upstairs in a Concordia building with a door that closed and locked. It was spacious enough to hold a good amount of people, and made for a more intimate, let’s say, environment where a certain safe space and facilitator’s authority was able to be held but people would still feel free to contribute or ask questions.

FM: I guess, in that way, you do need physical spaces that can at least work with the ‘space’ of a workshop, rather than against it. The story you told is an interesting one in terms of those rules of behaviour I mentioned earlier but also in terms of audience. I mean, I think that it is 100% the job of the privileged group to seek out knowledge, rather than the oppressed group constantly trying to provide it, but there is a tendency with workshop environments to have a certain participator in mind and it does make for a lot of familiar faces and fewer new ones, depending on the type of facilitation/discussion you’re running. Part of this could very well be due to the transient nature of the physical spaces, which makes things less accessible, but I also think that there are a lot of people who just aren’t willing to participate in this sort of knowledge production, aren’t interested in entering the mind ‘space’ of the workshop. What do you think about this problem? Do you see it as a problem? What can or should be done, in your opinion? Also, do you think that this sort of issue of audience is the same across the board for the different sorts of anti-oppression workshops you’ve run or do you think there are differences and, if so, why?

TK: Well, I guess it mostly comes down to an issue of mental and emotional labour. Of course there are going to be more belligerent attendees, and the amount of effort that it takes to deal with them aren’t necessarily fair to ask from facilitators who are of marginalized groups, whose knowledge runs a risk of being deemed too ‘subjective’ by these attendees. My personal opinion is that more privileged allies should be involved with workshops- those who can listen and help the marginalized facilitator speak from their depth of understanding, while being the one who doesn’t have to put in as much effort and is not at as much risk as the marginalized facilitator when dealing with a more resistant audience.

The knowledge being produced for an audience in a workshop is a very constructed and thought-out process designed to open up a discourse in every attendee’s life- interruptions are accounted for, and actually often lead to very interesting discussions (once during a trans 101 a discussion on preferred pronouns that hadn’t been part of the workshop was opened up and was very involved and enlightening) but it only works when the space has a clear respect for the facilitator, and subsequently for the process of knowledge production being brought to the session.

It’s a bit of a dilemma, I guess. I’ve been to many a workshop where it was simply me, the facilitator, and a bunch of people already involved with the cause and frankly didn’t need the workshop. I definitely think workshops need to reach a broader audience and those outside of the organizing groups, but that runs the risk of having attendees like the tall guy I mentioned. In an optimal world, facilitators would always be paired with one who is part of the marginalized group being taught about and one very adamant ally to sort of verbally wrassle down some of the more problematic attendees (laugh). Workshops for social justice issues still tend to be very small-scale efforts with little funding- as I mentioned earlier, Concordia had plans to integrate mandatory consent workshops for first years in the residences that fell through- and levels of security, safety, and authority are slippery things to maintain without bigger forces to back us up. And even with official sanction, it tends to become difficult to reach people with a workshop- I remember my first year in undergrad having a mandatory dorm workshop on various issues near the beginning of the year. I heard many complaints from my floormates before and after the workshop, and even found people skipping it because they found it ‘stupid’ and ‘unnecessary’ (which is quite inaccurate given the rate of sexual assault in dorms and, speaking from personal experience, the disregard for my queerness or pronouns). I very much appreciated that the RA for my floor was very strict about attendance, and felt that it did create an environment where I felt safer talking about and pointing out bad experiences than it could have been.

So. There’s no concrete solution I’ve come across yet, but I guess it comes down to that- more vigilant allyship from people and organizations in positions of power and authority.

The post Workshop Facilitation and Transient ‘Space’: An Interview appeared first on &.

]]>The post An anonymous interview with TAG student member appeared first on &.

]]>When approaching professors and professional members of TAG, I was told I should consider interviewing student members about the Lab and the forms of knowledge they create. Therefore, I sought to interview two student members from different disciplinary backgrounds. Unfortunately, the other student was unavailable for an interview before the 15 of December. If possible, we will conduct our interview at a later date and I shall update this post to demonstrate the plurality of voices found within TAG.

In this interview for Mess and Method [Fall 2015, “What is a Media Lab?” edition], Marie-Christine Lavoie speaks with an anonymous student member from Concordia’s Technoculture, Art and Games (TAG). This interview seeks to understand how different members understand and define TAG, and how the lab produces knowledge. Overall, this interview seeks to obtain an inside look at how TAG functions within Academia. This interview was conducted through email correspondence.

ML: Hello and thank you for agreeing to this interview. If possible, could you briefly explain the benefits, or the reason, for remaining anonymous?

A: Note that this won’t actually be anonymous, even if you don’t include my name, because of the other information you’ve asked for and the small size of the lab. It’ll be easy to guess who I am. Knowing that, I’m self-censoring to some extent because it’s dangerous not to. Professors don’t like to acknowledge this, but they hold a fair bit of power over us as students, since they’re the ones who mark our papers, write us letters of recommendation, sign off on RA contracts, grant us permission to use the lab, and so on and so forth. Those hierarchies make it very difficult for a student (or staff member) to be open and honest about their thoughts or experiences. Marginalized people, and students who are not Canadian citizens and/or don’t have access to scholarships or support from their families, and so are relying on RA contracts for their survival, are particularly vulnerable.

ML: Thank you for taking the time to do this interview considering these circumstances.

ML: Can you introduce yourself? What lead you to this field of research, and what kind of work happens on a daily basis at TAG?

A: I’m a 3rd year PhD student in the Humanities program, but I’ve been with the lab for…6 years now? Something like that. I got involved with the lab through the student-run 5a7s[1]. Eventually I was asked to work on a research assistant contract, which sort of made me a member by default. I got involved in games for two reasons. The first was that a lot of my friends in my undergrad played videogames, and some of them played a LOT, and I wanted to know why. I’d mostly stopped playing games myself, aside from the occasional round of Mario Kart, and we had very few games in my house growing up, so I think I was curious. At the time I was doing a Fine Arts degree, and feeling like the art world was this really insular thing, composed mostly of artists talking to other artists and art critics, but not the general public (sound familiar?). I wanted to work with a medium that more people could relate to and access, and games seemed like a good candidate. I knew almost nothing about games at that point, or game studies, or media studies, so it was a steep learning curve when I started my MA based on a project about digital role-playing games.

ML: Could you explain what TAG is and what it means to you?

A: That’s a tough question. I used to have what in retrospect seems like a very optimistic and naïve view of TAG. Mostly it seemed like a great way to meet people and get involved in interesting projects. It provided a lot of opportunities and a sense of community that I wouldn’t have had if I’d just stuck to my MA program. That’s still the case, but I’m much more aware of the costs and limitations of the space and the institution it’s a part of. I like the way Sarah Ahmed puts it, “we learn about worlds from the difficulties we have transforming them.” Thanks to that, I’m more aware of the different ways that women and men, for example, are treated, and of the hypocrisy that is so prevalent in the humanities, where people tend to see themselves and their work as progressive almost by default, while remaining completely unaware of their own privilege/power or the role they play in perpetuating an abusive and exploitative system. I’ve seen how people get pushed out of the space, and silenced in the name of protecting reputations and avoiding “conflict.” I also feel like TAG is somewhat unwittingly playing along with the neoliberalization and corporatization of the university. We’re benefiting from the fact that games are “big business,” which means that we’re able to attract funding where other research centres or fields cannot, but it increasingly feels like that funding comes with conditions and/or tacit pressure to collaborate with the industry in some way or another, and that really frustrates me. Public-private partnerships always sound good on paper, but in the end all we’re doing in funneling more public money into private hands, a process that is eroding democracy and further impoverishing people who rely on public services and social support networks. That doesn’t mean of course that there aren’t lots of benefits that TAG provides to non-commercial initiatives or organizations, or that there aren’t people within TAG that are critical of these processes, but it’s the big picture that really worries me.

ML: TAG stands for “Technoculture, Arts and Games”, but what do you make of this name? What does it mean in the context of the work you are doing in this lab?

A: It’s a pretty vague title, and I guess that’s positive in the sense that it allows for more flexibility and breadth in the kind of research that fits under the TAG label. But honestly I’ve never been very interested in defining art or games, let alone technoculture, because every time I see someone try to impose a fixed definition on these things it ends out being exclusionary and/or limiting rather than helpful.

ML: So then what do you think of TAG’s label as “an interdisciplinary centre for research”?

A: To me it means that people come from very different backgrounds and disciplinary fields, or that they don’t belong to any one field in particular. I think it’s how things should be to be honest. Disciplinary silos are a result of institutional pressures and the need to distinguish yourself from the “competition,” but I don’t think they’re helpful overall. In fact, they can be incredibly harmful, especially when they help to justify the complete elimination of critical discourse or thinking from a curriculum.

ML: TAG is often referred to as a Game lab, what do you think of this definition? Additionally, is TAG unique compared to other labs on and off campus?

A: Well it makes it clear which letter is being prioritized in the TAG acronym. I don’t think the definition is inappropriate or inaccurate, although it could definitely be acting as a barrier to anyone who’s not primarily interested in games. It’s hard to know how TAG compares to other labs because I haven’t spent nearly as much time in other labs. It definitely feels different to me than other spaces, but I have no idea whether or not it’s unique.

ML: As a spaces involved in the formation of knowledge, how does the surrounding labs affect TAG?

A: Occasionally there are collaborations with other labs or people who move back and forth between them, but for the most part there doesn’t seem to be much interaction. I think in some ways labs are often made to compete with one another for space and resources, and that combined with the fact that we are all subjected to productivity metrics that force us to concentrate on our own work at the expense of forming collaborations or taking on new projects makes it more difficult to form lasting relationships with other labs. The sense I get is that TAG is the “golden child” of Concordia’s upper administration, both because it helps to attract new students and is working in an area that the government sees as a key site of economic development.

ML: Bruno Latour explains in Laboratory Life that Laboratories produce knowledge that can become facts and/or artifacts. What kind of knowledge or facts does TAG output? If you had access to different equipment or facilities, would this knowledge, this output, change?

A: That’s hard to talk about succinctly—it’s all over the place. Certainly people are learning how to make games, and we’re also practicing and experimenting with different ways of talking about games. For me though, I feel like the most important knowledge I’ve gained/produced has been mostly about the internal politics of the university, the politics of games, and how these relate to broader power structures. TAG is a place where I can see how these dynamics play out, and I can analyze them based on knowledge I’ve acquired outside or on the margins of the university, mostly through interactions with other people and the things I’ve read online. But I wouldn’t say that this is the case for everyone, or even most people. It’s certainly not the kind of knowledge that is being officially sanctioned or published—if anything, it’s feels like it’s being repressed.

I actually think it’s a mistake to reduce “knowledge production” to writing. It’s even worse to reduce it to writing that conforms to academic standards and protocols, like the peer-reviewed journal article or the book chapter. Even though TAG does produce those things, I personally see this as the least important form of knowledge work we do. I know this makes me a bad academic, but I hate writing for other academics, according to all the unspoken codes about how you should or should not say things. It’s incredibly restrictive, it makes it almost impossible for me to write about what I really care about, and it makes everything I write inaccessible to all but a few elites. The knowledge work that I do that I really care about are my blog posts, Facebook comments, conversations, resource lists, lectures. It’s the articles and videos that I pass on to friends—because even if we don’t produce those things ourselves, serving as a conduit to alternative narratives and critical analysis is important work. It’s the objects I make (or try to make), like the game I’m working on about gentrification, and the experiences I create by organizing and running events. All of this matters so much more to me than journal articles, and I’m going to resist writing them, because I think the way we value and rank knowledge, the way we decide what “counts” as knowledge, is broken. We’re all being held hostage–because everyone knows that your academic career is dependent on your publication count–but we’re also the ones reinforcing that system by playing along and following the rules.

I wish TAG would play a more active role in advocating for alternative forms of knowledge production. if we’re going to change this broken system, which by the way is incredibly profitable for major publishers that are benefiting from all this unpaid labour, we need an organized, sustained campaign. As students, we also need reassurance from professors that they won’t pressure us to publish or punish us for not following the standard academic protocols, that they will make efforts to change how hiring committees work whenever and wherever they have the power to do so, and that they’ll support us if we decide to take the fight to the upper admin. I realize this is wishful thinking, but I do think that this is what’s necessary if we want to see substantial changes in how the system works, and who benefits from it. I don’t think that new equipment or facilities would have that much of an impact on the kind of knowledge that is being produced. I think a much bigger factor is the kind of cultural shift that has been taking place over the last year or two. But that’s a long, slow process.

ML: Could you talk about the kinds of projects TAG is involved with?

Oof there are tons. Off the top of my head, there’s speedrunning, “serious games” and education, virtual reality, Minecraft, modding, costume games, the Indie Megabooth project… Most of them I’m not qualified to talk about because I don’t know enough about them. TAG also runs a lot of workshops, game jams, public arcades, and so on. These things have an impact, although I sometimes wish that more of what we did was politically engaged and critical and formatted for the public rather than other academics. Gamerella [2]is great but we need more of that, and not just for game-makers. There are so many conversations that we could be having but aren’t. There’s also the fact that TAG, like pretty much all academic institutions, has a tendency to colonize the work of surrounding communities, individuals, and organizations. It can do this because TAG members are often involved in projects outside of TAG, and it’s easy to classify the work they do as TAG projects, even if this isn’t how they are being presented or conceived of by the people actually doing the work. In some ways it’s the price we pay for the institutional support and resources TAG provides. Whoever has the money gets to call the shots, and take the credit.

ML: Could you talk about the TAG community? How has/could the community help you with your goals?

A: Parts of the TAG community are very close, and there is a lot of mutual aid and support, which is wonderful. There’s also lots of conflict and tension, people who are being unintentionally excluded or marginalized, and disagreements about how the space can or should be run. I feel like I’ve personally invested a lot in the community, and while there has been a lot of stress and pain that’s come out of that, and a lot of lost trust, it’s also been rewarding in a lot of ways. TAG is also a very fluid community, because as I mentioned so many of the people involved in TAG have connections outside of that, and so it’s hard to separate it completely from other spaces, like for example [3]MRGS or [4]Pixelles, just because there’s so much overlap in terms of who’s involved.

ML: Could you talk about the process involved in become a TAG member?

A: Well there are the explicit rules, and then there are the implicit rules. In my experience it’s the implicit rules that matter, since the explicit rules can usually be bent. Most of the TAG members are Concordia graduate students, and it’s definitely much easier to become a member if you have student status. It also helps if you’re a white cis man, although we’re making efforts to change that. It helps if you don’t have children, if you can afford to live in the city, if you’re able-bodied and neurotypical, if you like to drink beer and don’t need a job to support yourself, if you can speak and write English fluently, if you’ve played a lot of games since a young age, if you’re familiar with academic jargon, if your politics aren’t too radical, if you don’t mind being hit on, and so on. Technically the people who don’t fall into these categories are allowed to be members, but that doesn’t mean they’re able to participate or have access to the space to the same degree as people who do meet these criteria. Also most of this is never really talked about openly, even though there are a lot more conversations about these things now then there were when I first started coming to TAG, thanks in large part a lot of hidden, unacknowledged labour that’s been going on behind the scenes.

ML: What kind of equipment can you find in the TAG lab? Are they useful to everyone? If not, why is it so important to have these (sewing machines, 3D printer, computers, gaming consoles, etc.)?

A: Not all the equipment is useful to everyone, but that’s not necessarily a problem so long as someone is using it. I actually find the equipment most useful when it comes to running events or workshops. That said, most of what I borrow comes from Hexagram (or what used to be Hexagram), not TAG. If we need laptops, projectors, cables, consoles, keyboards, etc. it can be really helpful to have a large pool that we can draw from. I’m involved in running a small non-profit and we would never be able to afford this equipment otherwise, so in that sense it’s incredibly important. It’s just a shame that access to most of the equipment is limited to students or professors. One of the things I think students can do, aside from fighting these institutional restrictions, is to serve as conduits or relays so that people outside the institution, i.e. the general public, can also make use of this equipment.

ML: TAG recently relocated to a new, more open space. What kind of spaces do you have access to as a member of this lab? Do you feel the new space is better?

A: I like the new location. It’s a nicer room than the last one, it’s bigger, and we have a better view. Having the small side rooms is also useful when you want to have a private conversation and need somewhere to go. Personally I find it hard to get work done in TAG most of the time, because there are so many people there and I’m easily distracted. I don’t use the equipment much because I tend to just work on my laptop, so as long as there’s a free table and a chair I don’t really care about the layout—I’ll work anywhere.

Aside from the TAG rooms, I also have access to the Fine Arts Research Facilities (FARF) labs and work spaces. Having access to these is definitely useful, mostly just as relatively quiet places to meet and work. On a less formal level, I have access to other labs and conferences partly as a result of my affiliation with TAG. If I wanted to it would be fairly easy for me to go to just about any other game lab for a visit.

ML: Do you think these spaces are unique compared to other spaces? Is there anything you would change?

A: I don’t know if they’re unique. Maybe in some respects, but I also think they very much reflect what’s going on in the rest of the world. There are lots of things I would change if I could. I would try and eliminate, as much as possible, the hierarchies that exist, redistribute funding, and increase transparency in order to democratize the space. I would try to forge more connections with activist communities and marginalized populations that really need access to the things we so often take for granted. I would dismantle the university system and rebuild it, eliminating grades, exams, degrees and everything else that’s built on the myth of “meritocracy” but that ultimately ends out reinforcing structural oppression. But in order to do that we’d have to change the entire society.

ML: Could you tell us a bit about the project you have done, are doing, or are thinking of doing as part of TAG? How does someone’s project become a TAG project?

A: I’m looking at indie and alternative game communities/organizations, how they function internally, and what their role is in the broader videogame ecosystem. I’m on the board of the Mount Royal Game Society and got involved in that organization through the people I met at TAG, so in that sense my work there has always been connected to TAG, although as an organization we try to do things independently wherever possible. The problem is that as a small non-profit, we are always somewhat reliant on large institutional bodies or other holders of physical and financial capital in order to do the work that we do, i.e. organizing and running events. There’s also the fact that it’s only by incorporating my volunteer work into my PhD that I’m able to dedicate as much time to it as I do, and I’m worried about the implications of that relationship. We’re lucky that most of the time there are very few visible, explicit strings attached whenever we ask for money or support from TAG, but it’s still a form of dependency that is uncomfortable at best. So for me there are definitely benefits to being associated with TAG, but it’s not as straightforward as that question suggest.

ML: Thank you for taking the time to write this interview. Do you have anything you would like to say to our readers?

A: No problem. I don’t think I have anything to add. I’m not really happy with the projects I’ve done in the past, so I’d prefer not to talk about them, and the things I’m doing now are collective efforts, and not something I feel comfortable classifying as “TAG projects.”

ML: Again, thank you so much for this interview and best of luck during the end of semester.

[1] “TAG students also organize a weekly open house between 5 and 7 PM, where researchers and members of the community get together to play, talk and create game related works. These events are open to the public and we encourage anyone interested in becoming involved with the Centre to stop by and learn more. This is the first entry point to TAG and is the BEST way to meet people and learn about what we do” http://tag.hexagram.ca/about/

[2] “GAMERella offers the opportunity to meet more women, PoC and gender-non conforming people (as well as anyone who support minorities in the industry) interested in game development. TAG wishes not only to encourage underrepresented people and first-time game jammers to join in on the excitement, but also to celebrate the representation of diversity in the videogame community” http://tag.hexagram.ca/gamerella/

[3] The Mount Royal Game Society http://mrgs.ca/category/games/page/4/

[4] “Pixelles is a non-profit organization dedicated to empowering more women to make and change games, founded by Tanya Short and Rebecca Cohen-Palacios. Pixelles organizes free monthly workshops, a mentorship program for aspiring women-in-games, game jams, socials and more” http://pixelles.ca/

The post An anonymous interview with TAG student member appeared first on &.

]]>The post “It’s all about building trust”: An interview with Joanna Berzowska of XS Labs appeared first on &.

]]>Joanna Berzowska founded XS Labs in 2002 at Concordia, where they focus on “the development and design of electronic textiles, responsive clothing, wearable technologies, reactive materials, and squishy interfaces.” Previous to XS Labs, Berzowska studied and worked at the MIT Media Lab, and she co-founded International Fashion Machines with Maggie Orth. She holds a BA in Pure Mathematics and a BFA in Design Arts.

The kind of work that Berzowska engages in is profoundly interdisciplinary and crosses distinctions that we might automatically put up between design, industry, art, and theory. Her work has been shown at the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum in New York, the V&A in London, and at Ars Electronica in Linz, Austria, among others. Her lab at Concordia is located on the 10th floor of the EV and is part of the textiles cluster.

I met Joanna Berzowska for a coffee in St. Henri on December 10 to discuss wearable technology, her experience working at the MIT Media Lab, the agency of things, and what she believes is important for building an interdisciplinary space.

First of all, why do you call XS Labs a “lab”? Instead of say a “studio”? With International Fashion Machines, for example, I notice they call themselves a “company” — why “lab”?