The post Fugitive Sound appeared first on &.

]]>The following is an excerpt from the middle of my paper “Fugitive Sound: The Phonotext and Critical Practice,” read at the MLA convention in Vancouver, for the panel Weird Media.

–Michael Nardone

+

In regard to poetry and poetry criticism, we’re in a moment of considerable or growing interest in and engagement with poetry phonotexts produced in a variety of formats. I see this growing interest mainly due to the specific format that the majority of poetry phonotexts now circulate – the MP3 – and to the specific digital collections that curate – perhaps the better word is publish – these phonotexts, such as PennSound, UbuWeb, and SpokenWeb. In addition to these collections, there have been a few critics who for years have argued for the importance of critically engaging the phonemic aspects of works, and the social and technological infrastructures that support these performances and their media. Yet, despite these digital repositories and despite the contributions of these writers, literary critical practices for engaging the sonic aspects of poetic works are still rather limited and remain largely unexplored.

An example will help illustrate these particular limitations. I’ve recently completed an essay on the American poet, composer, and multimedia artist Jackson Mac Low. The essay focuses on a specific 1971 reading by Mac Low in Montréal. During the reading, Mac Low collaborates with a up to a dozen people at once of people on his improvised, constraint-based score-poems. Mac Low is rather well-known for these kinds of multivocal and participatory performances, but what makes this performance remarkable is his other “collaborators”: 4 reel-to-reel players that he is constantly manipulating and playing throughout the performance: he actually refers to them as collaborators several times during the performance. On the four reel-to-reel players, Mac Low is playing from his personal reel-to-reel collection of his own performances. In reading one of his “Simultaneities,” Mac Low plays four distinct prior performances of the poem. In this sounded aspect of his performance, Mac Low is not simply aiming to produce a certain palimpsestual or palimtextual noise, though, throughout, there are many moments of cacophony. Instead, this practice is a way to open up the site of the performance to other collaborators, to extend and tune the acts of listening in that space and time to other spaces, other times, and to develop ways to relate and respond to those sounds in their own performance of the poem.

Examining the breadth of criticism on Mac Low’s works, one can find exceptional passages thinking through the pluriformity of a Mac Low poem, recognizing them as multimodal: the poems exist simultaneously as instructions for performance, as performance, and, often, as some kind of text-document that is produced out of performance. Here, the sonic aspects of Mac Low’s works are always acknowledged as being a crucial part of the performances, yet the sounds are not in and of themselves directly addressed. Two exceptions are found in the writings of Tyrus Miller and Hélene Aji, who detail specific performances and the concept of sound in the those works. Yet, despite the great care with which Aji and Miller discuss the sonic aspects of Mac Low’s repertoire, neither writer actually listens to the works. When they discuss the sounded elements of Mac Low’s works, they rely solely upon the scores for performance: either the poem-text or the instructions for performance. This is to say that each time Aji and Miller discuss sound in Mac Low’s works, they are writing about an abstraction of sound based upon what Mac Low intended as author and composer, as opposed to the sounds produced in performance in and of themselves. This is also to say that for all of the attention that Aji and Miller give to the specificity of Mac Low’s instructions for performance, they willfully ignore the imperative that Mac Low pronounced on numerous occasions to be his primary admonition for performance: “Listen! Listen! Listen!”

This is only one example, but this approach is very much the case in critical writings if they choose to engage with the sounded elements of poetic works in the first place.

The omission of the phonotext exposes a certain critical limit in textual scholarship as being unable to engage the pluriformity of poetic works. Even media-centred anaylses like the ones of Mac Low’s poetic repertoire insist upon the centrality of the written document, the grapheme and substrate of paper. This omission makes a certain degree of sense: Literary scholars are, after all, trained to read closely and interpret texts. Yet this reliance upon a conception of the poetic text as primarily a graphemic document, especially when considering the expanded field of poetic practice, seems an inadequate endeavor at its very outset.

So, what I want to begin to develop here is a media-centered approach to think about specific modes of textuality, inscriptions across an array of formats – here, I’m looking to Friedrich Kittler, Johanna Drucker, and Jonathan Sterne – and to combine that approach by paying close attention to writers working today at the interface of literary studies, performance studies, and black studies – Nathaniel Mackey, Fred Moten, Daphne Brooks, Alexandra T. Vazquez, in particular – who think about phonotextual production over series of lived, embodied events.

It is the latter set of writers – with particular attention to Moten –I’ll focus upon in these remaining moments – and this is a cursory sketch at the moment – and I want to do so specifically with regard to a concept of fugitivity. To do so, first, I want to route – note ROUTE, as opposed to its homonym ROOT (see Gilroy) – a concept of the fugitive back through the early history of sound recording technologies. Thomas Edison, in his initial reflection on the phonograph entitled “The Phonograph and Its Future” (1878), writes these opening sentences: “Of all the writer’s inventions, none has commanded such profound and earnest attention throughout the civilized world as has the phonograph,” then notes the “almost universal applicability” of the instrument’s “foundational principle”: “the gathering up and retaining of sounds hitherto fugitive.” Shortly thereafter, Edison lists his five “essential features of the phonograph”:

- The captivity of all manner of sound-waves heretofore designated as “fugitive,” and their permanent retention.

- Their reproduction with all their original characteristics at will, without the presence and consent of the original source, and after the lapse of any period of time.

- The transmission of such captive sounds through the ordinary channels of commercial intercourse and trade in material form, for purposes of communication or as merchantable goods.

- Indefinite multiplication and preservation of such sounds, without regard to the existence or non-existence of the original source.

- The captivation of sounds, with or without the knowledge or consent of the source of their origin.

Counter to this idealized captivation, and against the rhetoric of enslavement and commodification of sound in which Edison steeps the dream of his phonograph’s future, Fred Moten [in his Theorizing Lecture “Black Kant (Pronounced Chant)”] imagines a “lawless phonography,” a trajectory of sound moving with “dispossesed and dispossessing fugitivity in its very anticipation of the regulative and disciplinary powers to which it responds.” Here, Moten theorizes, via Foucault, how sound is not “totally integrated into techniques that govern and administer it, it constantly escapes them.”

I see Edison’s and Moten’s articulations of the fugitive as limit cases for considering the regulation and migration of sounds and of the phonotextual object. Embedded in Edison’s techno-fantasy are actual inscriptions, though they are impermanent and format-specific retentions of not “all,” but specific and contingent characteristics of performance. The sound recording instrument itself is a part – in certain instances, a collaborator, in others, a warden – of that performance’s reiterations. Here, one could imagine Edison’s machine-centered perspective as a precursor to Kittler’s own writings on sound recording technologies, writings that are exceptionally important for their scrutiny of how and what machines are actually doing, yet fraught for their notable absence of the political economy and the cultural practices in which the machines are produced and used.

At the core of Moten’s notion of fugitive sound is an acknowledgment of differential inscriptions, a sense of inscription that is technological, and also affective, embodied. Yet, there are inscriptions; there is a capture: there needs to be a mark, a marking, a marked body for a sound to resound. Here – in beginning to construct notions of a phonocritcal practice –one might ask: What is inscribed? How is it inscribed? What exceeds a specific inscription, and what are the means by which it is exceeded. To bring this back to poetry sound recordings, here, one is reminded that the phonotextual object is a record of – and a record produced by – dynamic living agents. To perform a poem is not simply to ossify one’s voice to the record, but to lay down your voice in the hopes of being revisited, or being revised (see Vazquez).

In Moten’s emphasis to depict the cultural techniques by which sound-waves are captured – how they are “governed and administered,” to use his own terms – in some occasions “without consent,” to use Edison’s repeated phrase – one confronts a politics of recording and recorded sound that ought to be a point of reflection for any critical engagement with a phonotextual object. Who is recorded? How is it recorded? What is the subject of the recording’s relationship to those who are recording and the technologies they are using to record? So, again, to bring this back to the poetry sound recording, this is an interesting point to think about institutions that produce and archive the recordings – there is a big difference between PennSound or Harvard’s Woodberry Poetry Room and, say, Andrew Kenower’s A Voicebox, a collection of recordings that is not financially supported in any way and emerges out of a very specific non-institutional space of community poetry readings, and I think this is something that needs to be considered further, and is simply one of many points to think about in terms of the regulation of sounds.

The post Fugitive Sound appeared first on &.

]]>The post The Kanye West Phonotext: sampling, sharing, re-appropriation and racism appeared first on &.

]]>As a “graduate candidate” in literary studies, I often ask myself whether my analyses of unpopular, neglected poems, novels and plays are culturally relevant. This short essay considers some things that are perhaps too often ignored by English scholars — the immense relevance of American popular music, how music relates to current trends in culture and consumerism, and the manner in which most ideological and aesthetic exchanges occur in the phonotextual virtuality of the internet. In an interview on “Sway in the Morning,” Kanye West claimed that nobody can achieve more cultural relevancy than a “rap rockstar.” And it might be that Kanye is not completely wrong; he may even be right! Jason Birchmeier, a contributer at allmusic.com describes West as: “Far and away the most adventurous (and successful) mainstream rapper of the new millennium, changing his sound and style with each new album.” But when I think about Kanye, I don’t think “musician.” As can be attested to by those of you (suckers) that went to see him live at the Bell Centre last February, West thinks of himself as much as a clothing designer, a poet, and a visionary as he does a rapper or music producer. Part of this “rap/rockstar’s” success, according to Sway, is demonstrated in West’s capacity to “manipulate the internet,” to draw attention to the Kanye brand through the avenues of fashion, through YouTube, through paparazzi scandals, and so on. All of this demonstrates that in the world of hip-hop, cultural “relevance” does not merely rest in selling albums, nor does it rely on getting people to listen to mp3s; more important (at least to Kanye West) is in connecting looking with listening, in drawing phonotextual links between these virtual conglomerations.

In Jonathan Sterne’s terms, the internet has introduced “new praxeologies of listening,” permitting music to be more than a container of containers (as Sterne describes the mp3), but a platform of outward links. Sterne describes how the mp3 marks a change in the economy of musical exchange, introducing a situation where “data could be moved with ease and grace across different kinds of systems and over great distances frequently and with little effort” (829). But this “possibility for quick and easy transfers, anonymous relations between provider and receiver, cross-platform compatibility, stockpiling and easy storage” (829) is old news in the world of hip-hop. For decades, hip-hop has relied upon an interactive collective phonotext exceeding sound. As Jeff Chang shows us in his insightful “History of the Hip-Hop Generation,” the musical innovations of spread like fire in the late-70s: “cassette tapes passed hand-to-hand in the Black and Latino neighbourhoods of Brooklyn, the Lower East Side, Queens, and Long Island’s Black Belt” (127-28). Hip-hop has always been a “hyperlink” musical genre. When it comes to rhymes, breaks and beats, the logic of rap eludes most of the rules of “intellectual property” that constrain scholars in academic institutions. Borrowing, sampling, sharing and stealing are in fact crucial parts of the collaborative “phonotexts” that hip-hop inevitably opens up. According to Greg Tate, the hip-hop generation is always “about ten years ahead of culture in terms of embracing [and utilizing] technology” (43). We see how hip-hop takes the music sample to embody “an item that ‘works for’ and is ‘worked on’ by a host of people, ideologies, technologies and other social and material elements” (Sterne, 826). Drawn out of the noise of the internet and ripped from previous songs, the sonic trafficking done by DJs does not produce original scores so much as generating remixes and re-appropriations of previously recorded media. Social and material relations are always at the centre of the music. And as we see with the example of Kanye West, the lyrical emphasis on consumerism, race, and oppression are inextricable from the formal operations of technology, advertising, distribution, performance, and so on.

“Annotate the World” : Welcome to Genius

Sterne uses the mp3 as a “tour guide” through social, physical, psychological and ideological phenomena of which otherwise we might not have been fully aware; this essay uses Rap Genius as a means to discuss the same phenomena. “Annotate the world” is the Genius mantra. Search the relational database and you will discover a “world of communities,” each fixated on their own phonotextual genres (channels range from R&B genius, rock.genius; country.genius; news.genius; lit.genius; history.genius; law.genius; sports.genius; to many others). The site displays shifting narratives which vacillate between the critiques, rants and appraisals of participants. Everyone is eligible for an account, which allows for maximum participation in the collaborative annotation of the lyrics, aesthetics, production, and intertextual reference that occurs within and surrounding the thousands of featured songs. Rap Genius shows us how the internet can be used to organize, expand and store data about hip-hop, its history and relates all of this to current events. We also see how the interactive, visual, imaginative extensions of music take us outside the “contained” space of the mp3, beyond what Sterne describes as the “fine distinctions of the human ear” (834). Rap Genius, like the mp3, has altered the nature of the music recording industry as well as the actual and idealized practices of listening. Rap Genius is an internet hypertext mapping and storing the contours of hip-hop; it is an exegetic phonotextual knowledge base that is both structured and always open to alteration.

LOOP ONE : “New Slaves”

Sterne discusses mp3s as “cultural artifacts in their own right,” as a “psychoacoustic technology that literally plays its listeners” (825). As a means of testing the “Genius,” I began browsing the web pages associated with a couple of tracks from Kanye West’s newest album entitled Yeezus. How do fans and critics play with Yeezus? How does the mp3 “container,” in tandem with web-based music discussion boards open a situation where listeners, consumerism, culture and music play off each other? After all, “music” describes more than listening, viewing, sharing, trading, and stealing audio files, but represents a cultural dialogue — and in my view, this intercommunication needs emphasis. Thus how do the perplexing, ambiguous and infuriating messages of Yeezus escape simple hermeneutic interpretation, and demand an expanded virtual phonotextual analysis? Yes, Kanye sometimes raps like a misogynistic egomaniacal, elitist asshole, but this does not mean that his product is not of immeasurable capitalist and cultural value. If we are going to talk about “big data,” mass media, capitalist production via the phonotext, why not turn to the “rap rockstar” that ostentatiously proclaims “I am a god”? In the spirit of “distant reading,” as I browsed the site theory synchronized with scores of other cultural objects, feelings and images. Images of West’s clothing line led into vertiginous accounts of the American white establishment; ethics, bling, racism, politics, hate, hope, America. To view albums as single “containers,” as “cultural artifacts” is to ignore larger debates of what the world of music is doing. Rap Genius invites a formal analysis of music that acts, and thus aids in uncovering how a world of listeners are making sense of the larger controversies embedded within Kanye’s phonotext.

check out the link; you might even participate in the forum!

Here is a supplementary explanation about why Kanye thinks “we are all slaves”:

LOOP 2: “Blood on the Leaves” [Annotation from Rap Genius]

Sterne claims that the iPod introduced new ways of listening to music; and although mp3s are assembled by a variety of technologies, Sterne cites Philip Sherburne, that computer manipulation demonstrates “the ongoing dematerialization of music” (831). But when we listening to music through the channel of Rap Genius, what sorts of rematerializations occur? Take, for instance, “Blood on the Leaves” — where Kanye’s narcissistic lamentation about a break-up rematerializes the entire track of Nina Simone’s “Strange Fruit” — a mournful song about the lynching of countless African Americans. Jody Rosen criticizes the rapper is “well aware of how audacious it is to interpolate that sacred song into a monstrously self-pitying … melodrama about what a drag it is when your side-piece won’t abort your love child.” Meanwhile, the responses on Rap Genius include several extra-textual references that might help to make sense of the broader context of the song. One of the links posted is this video:

Rap Genius extends Jonathan Sterne’s evaluation of the “peculiar status of the mp3 as a valued cultural object which can circulate outside the channels of the value economy … enabling conditions for the intellectual property debates that surround it” (831). Kanye’s sampling of “Strange Fruit” ignites more than a conflict about intellectual property, but draws our attention to the reappropriation of a historical and cultural artifact, in this case one that explicitly speaks about the slavery and murder of countless African Americans. Although the original message of “Strange Fruit” is obscured by Kanye’s self-involved contemplations and the tight production of an aesthetically-pleasing song, Rap Genius displays how the phonotext cannot evade these illuminating and necessary debates.

LOOP 3:”Black Skinhead” (I recommend that you read the full Annotation for this one)

These are certainly not the first exemplifications of Kanye West’s words producing arguments about racism. But with Yeezus, merchandise may have generated as much public discussion about race than did the lyrics of his songs:

Through the “Genius lens,” merch becomes another component in the phonotextual narrative; although these images conflate and confuse matters, they also draw us back to the music. The jam’s provocative title is well-summarized by the Rap Genius community. (I found the link to the wikipedia entry on skinhead to be a very informative annotation for this track). As we have already developed, the re-appropriation (resyncing, remixing, re-defining) of symbols, iconography and lyrics (from the sacred to the profane) is one of Kanye’s greatest skills. These are, after all, perhaps the crucial components of any relevant phonotext — at least in the virtual world of pop. But can we take srsly this self-proclaimed “god,” this modern-day “Yeezus”? But when I turn to the news.genius channel, Zach Schwartz has this to say: Applaud Kanye West for Wearing the Confederate Flag

To conclude, Rap Genius offers more than some interesting table talk about sharing, sampling, re-appropriation, and racism. Kanye certainly “ain’t got the answers!” But at least phonotextual platforms such as these are getting us all to dig.

Works Cited

Chang, Jeff. Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation. Reading: Ebury Press, 2007. Print.

Cross, Brian; Mark Anthony Neal; Vijay Prashad; and Greg Tate. “Got Next: A Roundtable on Identity and Aesthetics after Multiculturalism.” Total Chaos: The Art and Aesthetics of Hip-Hop. Ed. Jeff Chang. 33-51. New York: Basic Books, 2006. Print.

“Kanye West – Black Skinhead.” Rap Genius. Genius Media Group Inc., 2014. Web. 5 Nov. 2014.

“Kanye West – Blood on the Leaves.” Rap Genius. Genius Media Group Inc., 2014. Web. 5 Nov. 2014.

“Kanye West – New Slaves.” Rap Genius. Genius Media Group Inc., 2014. Web. 5 Nov. 2014.

Manhatten, Chris. “Kanye West Flips Out On Sway In The Morning Interview Nov 26th, 2013.” YouTube. YouTube, 27 Nov. 2013. Web. 1 Nov. 2014.

Maya, H. “Nina Simone – Strange Fruit.” Online video clip. YouTube. YouTube, 29 Mar. 2011. Web. 7 Nov. 2014.

Rosen, Jody. “Rosen on Kanye West’s Yeezus: The Least Sexy Album of 2013.” Vulture. New York Media LLC., 18 June 2013. Web 20 Oct. 2014.

Schwartz, Zach. “Applaud Kanye West For Wearing the Confederate Flag.” News Genius. Genius Media Group Inc., 7 Nov. 2013. Web. 5 Nov. 2014.

Sterne, Jonathan. “The mp3 as cultural artifact.” New Media and Society 8.5 (2006): 825-842. Web. 20 Oct. 2014.

West, Kanye. Black Skinhead. Grooveshark, 2013. Stream.

—. Blood on the Leaves. Grooveshard, 2013. Stream.

—. New Slaves. Grooveshark, 2013. Stream.

The post The Kanye West Phonotext: sampling, sharing, re-appropriation and racism appeared first on &.

]]>The post Reading series/reading sound: a phonotextual analysis of the SpokenWeb digital archive (Al Flamenco, Aurelio Meza, Lee Hannigan) appeared first on &.

]]>The Reading Series

In the past twenty or so years, a large number of poetry sound recordings have been collected and stored in online databases hosted by university institutions. The SpokenWeb digital archive is one such collection. Housed at Concordia University, SpokenWeb features over 89 sound recordings from a poetry reading series that took place at Sir George Williams University (now Concordia) between 1966 and 1974. In the early 2000s, the original reel-to-reel tapes were converted to mp3, and by 2010 the SpokenWeb project, using the SGWU Poetry Series as a case study, was well into its exploration for ways to engage with poetry’s sound recordings as an object of literary analysis.

The collection’s ‘invisibility’ prior to its digitization (for over twenty years the original reel-to-reel tapes remained undiscovered, unreachable, forgotten, or deemed unimportant) is a glaring reminder of printed text’s monopoly in literary analysis and cultural production. Certainly, the written manuscripts of some of North America’s most important twentieth-century poets would not have collected dust for so many years, as did this collection of aural manuscripts — a collection which, as Murray and Wiercinski observe, “[draws] attention to the importance of sounded poetry for increased, complementary or even new critical engagement with poems, and . . . [disrupts] the marginalization of poetry recordings as a subject for serious literary research” (2012). However, before the SpokenWeb recordings became available in an online environment — before they became objects — they were an aggregate of inert documentary data — that is, a collection of archived materials (recordings, posters, newspaper write-ups) that together formed a unit of cultural production (reading series), shaped by bodies (organizers, audiences, poets), spaces (locales), and institutions (scholarly, poetic). Indeed, in order for a reading series to become a coherent object of literary study, its traces, what Camlot and Wershler call “documentary residue” (6), must be properly considered, for they are the constituents of meaning-making through which hermeneutic analyses of recorded audio filter. In other words, the SpokenWeb collection “urge[d] us to consider [the sound archive] as a result of social and technical processes, rather than outside them somehow” (Sterne 826).

As a coherent (if partial) unit of study, SpokenWeb, or the recorded reading series in general, allows us to return (if artificially) to an ephemeral live event, see beyond the archived document, and interpret it as an aggregate, one that is historically, technologically, and culturally specific. But how do we approach this aggregate? What might this particular phonotextual anthology tell us about modes of literary production in Canada in the late 60s and early 70s? How do we begin unpacking this data set? What does it mean to distant listen, or how do we read sound?

We began with an assumption, drawn from a recording of Robert Duncan’s 1965 lecture at the University of British Columbia, in which he speaks for over two hours, lecturing about poetry and poetics and reserving very little time for the reading of poetry in general, which seemed to oppose his claim of being a derivative poet.

Duncan, whose derivative poetic philosophy can be understood as a reincarnation of Romantic concepts of self-disintegration, highlights the inherently paradoxical nature of so many mid-20th century poetry readings — that is, existential consolidation of the poetic self through expository articulations of self-effacement. Which is to say, Duncan renounces the lyric “I” but uses a significant portion of his readings to talk about himself, a trend that proved true in his 1969 Poetry Series reading. This we determined by using the timestamps on Duncan’s recording to create a ratio between poems and extra-poetic speech. By extra-poetic speech we mean the content in the space between poems, where Duncan actually lectures about his poetry, provides anecdotes, or comments on his performance. Excluding George Bowering’s introduction, Duncan reads for two hours, six minutes and fifty-six seconds (another long session, by standard). For one hour and twenty-two minutes, he reads poetry. The remaining fifty-two minutes are filled with extra-poetic speech.

The balancing of poetry and poetics in Duncan’s reading led us to consider how other poets in the reading series might have organized their performance, and what that organization might reveal. For Duncan, it illustrated how aural performance can complicate poetic praxis. How do other poets organize their readings? Are there patterns to suggest that particular schools of poetry favour a certain structure of performance? Do poets begin readings with shorter poems, to ‘warm up’ their audience, and read longer poems in the middle? Do men read differently than women? Is there a relationship between venue and performance? Date? Time? Audience? The SGWU Poetry Series spanned nine years — would there be any recognizable changes in these patterns over that period? It became evident that the aggregation of reading series data could potentially reveal the social, historical, and cultural contexts that shaped the reading series, and also the underlying ideological structures within which the series took place. However, this information is difficult to access because the tools through which we attempt to do so are opaque (temporally, medially) and biased (i.e.who gets recorded, when, where and why). The reading series’ transcripts, it turned out, were a rich tool. But it wasn’t the shiniest.

Findings in the SpokenWeb archive

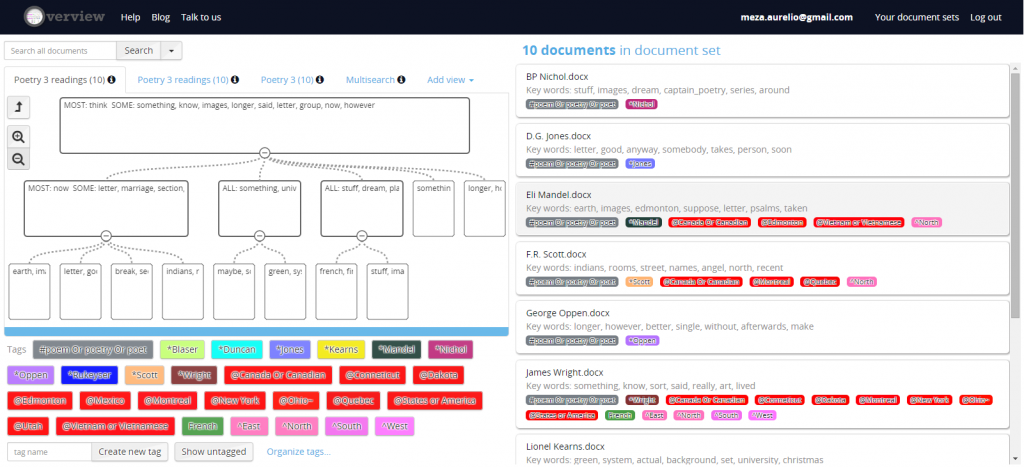

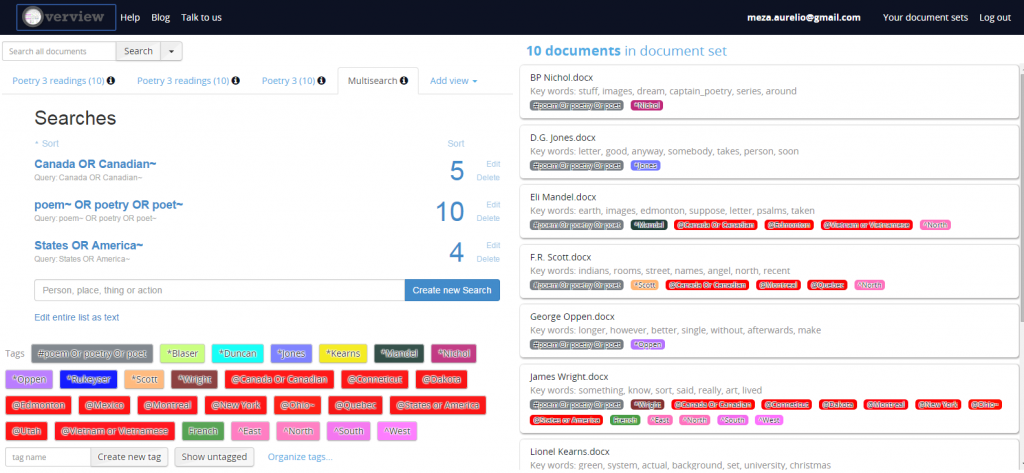

Fresh from Antonia and Corina’s workshop, we were excited to experiment with Overview, hoping to draw some quantitative results from the reading series transcripts. The possibility to tag, classify, and organize documents, as well as some of its visualisation tools, allowed us to access the documents in a different way, which went back and forth from a distant read to a close one. More than a visualisation program, Overview is an archive-classifying application; it helps to sort out big numbers of documents. In our case, it was not possible to aggregate all the readings made throughout the seven series, which would account for 65 poets. But we used the transcripts for the first three series and tagged the locations we found in them, in order to find if there were any recurrent mentions. Apart from topic classification, other functions of tagging include author/genre identification and reviewing control.

With our collections of extra poetic speech from the first three poetry transcripts of the SGWU Poetry Series, we began our tests with Overview with a specific question in mind: What can the extra-poetic speech, this “documentary residue,” tell us about the poets in this reading series, as well as their literary work? The “distant listening” approach we followed here to analyze the SpokenWeb archive suggests that these new forms of mediation have a strong influence on the way we consume, read, or listen to literary/cultural objects. Distant listening shifts meanings within the analytical process, and forces us to reconsider what is deemed important in a critical endeavor.

The fact that we were not able to analyse the poems read at every series (with few exceptions) guided our research to focus on extra-poetic speech. It is true that not all poets would explain in detail the content, form, or other aspects from their own work, but most of them would find it necessary to say a few words about it — and in some cases, such as Duncan’s, it would take a considerable amount of the reading time.

Although our approach was presumably distanced from the reading series as individual audio files, many initial assumptions were grounded in a close reading/listening approach. However, the fact that we could actually find patterns and correspondences among different readings helped us to identify whether these assumptions could be “quantitatively” confirmed. The use of tags on Overview to identify the mention of geographical data (places, locations, directions) provides significant information about how some poets perform their work in public, as well as it reveals some of the biases implicit in the reading series, which can probably be grasped by quickly skimming through the names of the invited poets, but which are confronted and confirmed through the tagging process.

One of these initial assumptions was that there was an evident slant toward North American/European authors, and therefore toward what Walter Mignolo, following Ella Shohat, would call their “enunciation loci”– the discursive “places” from which they talk about (2005). Nevertheless, can this assumption be proved through the methodological tools offered by Overview? Let’s have a look at the geographical mentions in the Poetry 3 readings, held throughout the 1968-1969 academic year.

Out of the ten poets who read in Poetry 3 (George Oppen, B.P. Nichol, Lionel Kearns, James Wright, Muriel Rukeyser, F.R. Scott, Eli Mandel, D.G. Jones, Robin Blaser, and Robert Duncan), most of them mentioned at least one city, country, or nationality. Although all of the poets were Canadian or American, only five of them mentioned “Canada” or “Canadian” (two Canadians — Mandel and Scott — and three Americans — Wright, Rukeyser, and Duncan). With the exception of Rukeyser, most of them also mentioned Canadian cities, such as Edmonton (Mandel), Montreal (Scott, Wright, and Duncan) or Quebec City (Scott, who was born there). It is significant to note that the three poets who mentioned “America”/“United States” are the same who mentioned “Canada”/“Canadian” (Wright, Rukeyser, and Duncan), so we might say that geographical location is more important for these poets than others in the series. Particularly in the case of Wright, he uses location in order to contextualize his work. Not only is he the one with more geographical references in Poetry 3 (he mentions Canada/Canadian, Connecticut, North and South Dakota, Montreal, New York, Ohio, and America/United States), but also the only one who uses the coordinates East/West to talk about different regions in the US.

What about non-English speaking locations? It is revealing to notice that only one poet (Scott) talks about Quebec, and not to refer to the province but rather to the city. In the light of the social events going on at that time, out of which the Quiet Revolution is the most remarkable, Scott’s solitary mention is actually revealing about the tensions and silences around social and political shifts in the region. Another major political event at that time was the Vietnam War, and only Duncan addresses it when he presents his poem “Soldiers.” In the case of Latin American countries, there is only one mention to Mexico (by Rukeyser, who like Samuel Beckett translated Octavio Paz into English) and one mention to Cuba and the Dominican Republic (Lionel Kearns).

These findings are provisional, as the whole SpokenWeb database has not been processed enough to reach to some general conclusions, but from preliminary analyses as the one above we can assume that most of the works performed in the Poetry 3 series were predominantly focused on North American places and (presumably) topics. Even the mentions to places outside North America, like Cuba or Vietnam, are connected to their relation with the United States.

Methods, Implications, Returns

Although we utilized overview as a tool that could enable ‘distant listening,’ our use of the software inevitably generated a typical close listening of the extra poetic speech that we derived from SpokenWeb. Our data sets from Poetry One, Two, and Three provided useful substance from which we could anticipate certain conclusions on topics such as poetic philosophy, performance tendencies, and topic content. Once we filtered our data through Overview’s algorithm, we began to question how this tool generated a novel set of information that we could not otherwise obtain from using keyword and word number searches in a standard word processor. Initially, it seemed to us that using software such as Overview would enhance our analysis of the material in a manner that would help us depart from a close read. However, we essentially returned to a typical literary approach to our extra poetic speech content through Overview. We had to reconsider our analytic stance towards this dataset, and to identify how exactly our examination would lead towards an effective distant listen of SpokenWeb. Ultimately, extra poetic speech does not qualify as literary text; first and foremost it is the speech sounds that precedes, interjects in, and concludes a given poetry reading. Extra poetic speech is inherently ephemeral – for unrecorded performances – given that it is spoken within the parameters of a reading environment and is not necessarily scripted in a physical document. However, with SpokenWeb, extra poetic speech is very much privileged as substantial and informative data in the form of audio recordings and transcripts. Naturally, a close reading of a transcript felt like the most organic analytic approach; yet, when we considered the forum — date, time, location — in which these poets delivered their readings and the significance of extra poetic speech, we began to reflect upon methods of cultural production and the tools that facilitated the Poetry Series’ preservation.

Phonotextual artifacts (collected in a database) provides invaluable material that enables us to consider things such as:

1) The physical bodies present during the reading

2) The physical space in which the reading occurred

3) Reading order among poets

4) Funding Methods

5) Performance styles

We have this dataset from the Poetry Series since individuals involved with its production recorded the readings on reel-to-reel analog tapes. Decades later, the formation of the SpokenWeb database created the necessary digital environment in which we can analyze and deconstruct MP3 sound recordings and written transcriptions that otherwise would have been lost given the readings’ ephemeral nature as spoken performances. This organized, catalogued, and coherent dataset produces a critical environment in which we can examine how these tools (reel-to-reel/MP3/database/transcripts) produce culture by re-creating the Poetry Series through contemporary technological constraints.

In this context, printed text does not hold its monopoly as the primary object in the fields of literary analysis and cultural production. Audio recording – and its component parts in the form of transcript and database – is one possible source from which we can mine digital data and derive meaning, creating new avenues to identify untraditional sources as the subject of literary analysis. However, we could not escape our methodological tendencies by applying a traditional close read. This phonotextual material perhaps necessitates a new methodology from which we can apply an appropriate analysis, or maybe it requires a blend of both close and distant (which we ended up performing). Regardless, the process remains opaque primarily because we were uncertain exactly what it meant to distant listen and read sound. We managed to derive some qualitative conclusions based on a set of quantitative data, but the most striking conclusion resulted from what we could perceive to be the relationship and evolution between forms of cultural production.

The SGWU Reading series recorded on reel-to-reel tapes represents a form of material cultural production. The reels themselves remained limited to a very small audience – perhaps even a non-existent audience prior to its rediscovery and digitization. Its conversion into MP3 entirely expands its material limitations given that it is widely disseminated across a broad audience with features that digitization and database cataloguing privilege. What began as a perfectly useless database (what Camlot described) now enables such endeavors as our specific experiment and the potential for others to perform countless other inquiries. As a form of cultural production, this multifaceted reading series (in its several manifestations) represents how our academic field broadens when expanded beyond print.

Works Cited

Camlot, Jason. “SGW Poetry Reading Series.” SpokenWeb. n.p. n.d. Web. 11 Nov. 2014.

—. “Sound Archives.” Beyond the Text: Literary Archives in the 21st Century Conference. Yale University. Beinecke Library, New Haven, CT. April 2013. Panel discussion. MP3.

Duncan, Robert. “Reading at the University of British Columbia, August 5, 1963.” PennSound. n.p. n.d. Web. 11 Nov. 2014.

Mignolo, Walter. “La razón post-colonial: herencias coloniales y teorías postcoloniales.” Adversus 2.4 (2005). Web. Nov. 2014.

Murray, Annie, and Jared Wiercinski. “Looking at Archival Sound: Enhancing the Listening Experience in a Spoken Word Archive.” First Monday 17.4 (2012): Web. 20 Oct. 2014.

“Overview Project Blog – Visualize Your Documents.” Overview. n.p. n.d. Web. 11 Nov. 2014.

Sterne, Joanthan. “MP3 as Cultural Artifact.” New Media & Society 8.5 (2008): 825-42.

The post Reading series/reading sound: a phonotextual analysis of the SpokenWeb digital archive (Al Flamenco, Aurelio Meza, Lee Hannigan) appeared first on &.

]]>The post Thinking sound and content through audio walks appeared first on &.

]]>“The content of a medium is like the juicy piece of meat carried by the burglar to distract the watchdog of the mind.”

— Marshall McLuhan

In 2001, while doing a residency at the Banff Centre in Alberta, Canadian sound artist Janet Cardiff recorded “Forest Walk,” an audio walk that takes listeners on a twelve-minute surreal tour of a wooded area in the small, Canadian Rocky Mountain town. Since then, she and George Bures Miller have published over twenty-five audio and audio/video walks for museums in Canada, the US, Germany, Denmark, Switzerland, Italy, Brazil and the UK. Here’s Cardiff conceptualizing the walks and describing how they’re made:

The format of the audio walks is similar to that of an audioguide. You are given a CD player or Ipod and told to stand or sit in a particular spot and press play. On the CD you hear my voice giving directions, like “turn left here” or “go through this gateway,” layered on a background of sounds: the sound of my footsteps, traffic, birds, and miscellaneous sound effects that have been pre-recorded on the same site as they are being heard. This is the important part of the recording. The virtual recorded soundscape has to mimic the real physical one in order to create a new world as a seamless combination of the two. My voice gives directions but also relates thoughts and narrative elements, which instills in the listener a desire to continue and finish the walk.

All of my walks are recorded in binaural audio with multi-layers of sound effects, music, and voices (sometimes as many as 18 tracks) added to the main walking track to create a 3D sphere of sound. Binaural audio is a technique that uses miniature microphones placed in the ears of a person. The result is an incredibly lifelike 3D reproduction of sound. Played back on a headset, it is almost as if the recorded events were taking place live.

Unfortunately, Cardiff and Bures Miller don’t make their audio walks available on their website. They do, however, provide a list of their collected works, bibliographic information for each walk, and, in some instances, short audio excerpts, such as this one from a 2000 walk titled “Taking Pictures” (headphones required for full 3D effect).

While Cardiff and Bures Miller’s walks do indeed create fantastical and disorienting combinations of soundscapes, I want to interrogate Cardiff’s use of the term “seamless.” There is no doubt that the walks are inimitably edited and produced, and to the naked ear they do indeed create a seamless combination of soundscapes. But this seamlessness is an illusion, and it is within these seams that Cardiff and Bures Miller reveal and disrupt the listener’s complacency in sound. What I mean by complacency is the passive acceptance of the sonic environments through which we move, and by disrupt I mean that they challenge the privileging of the visual in modes of cultural production. Cardiff and Bures Miller’s walks critique this privileging by de-naturalizing soundscapes and by blending fictional and historical narratives with listener expectations to reveal sound as a social construction. Listeners become hyper-aware of sounds that might otherwise be heard but not paid attention to. For example, in “Forest Walk,” birds chirping or trees rustling in the wind are natural sounds, part of the sequence of our everyday lives, which we seldom stand aside from. When recorded, they become mechanical, uniform and repetitive. Through amplification and acceleration, and when paired with such unnatural sounds as a piano playing in the distance or the voice of a human narrator, the fragmentary characteristic of a soundscape is made linear, fixed in space and time, and encourages listeners to consider what McLuhan calls a “subliminal and docile acceptance” of the sonic environment (20). Even while they remain passive recipients of aural information, so far as being instructed where to walk, when to walk there, and how to interpret what they’re seeing, listeners are persuaded to actively engage with and move through the conditions and contexts that make sound possible. In other words, they are invited to experience sound as event, as an orchestration of the fabricated nature of the ever-changing twenty-first century soundscape, of the way sound informs experience and guides action.

“The walks are really about play,” says Cardiff, “like the kids’ game, a letting-someone-guide-you, covering your eyes, wondering what they’ll do with you” (2000). “Taking Pictures” was made for the St. Louis Art Museum and commissioned by Wonderland, “a group exhibition that included ten artists whose art transforms space – whether architectural, formal, social, or psychological” (Steiner). Drawing from McLuhan, I suggest that the social and psychological transformation enacted through Cardiff and Bures Miller’s audio walks is not accomplished through their listeners (although they are the vehicles through which the transformation is realized), but through the sounds themselves, which generate new ways of listening by revealing sound as “a man-made construction, a colored canvas [that, like Cubist painting,] . . . substitutes all facets of an object simultaneously for the ‘point-of-view’ or facet of perspective illusion” (12). It does so “by involvement” (13) – that is, by drawing listeners out of a soundscape and depositing them into a reworked, narrativized, and re-presented version, where all sounds are artificial.

Cardiff and Bures Miller’s canvas is made of sound – but what is this sound about? In comparing their walks to cubist painting, where are the “dimensions on canvas, [the] patterns, lights, textures, that [drive] home the message by involvement”? (McLuhan 13). What does it mean when sequence yields to simultaneity, when we enter a “world of structure and of configuration?” (13). What are the phonotexts of our lives, and what does it mean to break into them, to show their edges and mark their place in space and time? “Perhaps it is necessary,” writes Jean-Luc Nancy, “that sense not be content to make sense (or to be logos), but that it want also to resound” (6). Cardiff and Bures Miller’s audio walks, by blocking out and recontextualizing aural experience, “by giving the inside and outside, the top, bottom, back, and front and the rest, in [three] dimensions, drop the illusion of perspective in favour of instant sensory awareness of the whole” (McLuhan 13). Or do they? The walks evoke “a desire to continue and finish,” yes, but they are by no means an entirely autonomous listening activity. They are standardized, choreographed, and rehearsed – interactive only insofar as they disorient and therefore remind the listener of sound’s materiality. While listeners maintain agency by deciding to participate in the first place, and while they extend that agency by choosing to leave their headphones in and follow the narrator’s directions (like good listeners), this agency is predetermined – participants have little control over what they hear, where they walk, or how long they listen. Of course, listeners, for the most part, can control how they are affected – they are free to respond in whatever way they choose – but even this autonomy is contained. Like a rat in a maze, listeners can act out agency but in a controlled environment.

Returning to Cardiff’s statement – “the walks are really about play” – I am reminded of Jonathan Sterne’s “mp3 as Cultural Artifact,” in which he suggests that the mp3 is “shaped by . . . actual and idealized practices of listening” (826). Cardiff and Bures Miller’s audio walks are similarly shaped. They are exercises in listening that occupy the space between actual (natural) and ideal (aesthetically pleasing/artistically charged): the sounds that are inherent in a particular environment, such as those heard in a forest, are overlaid with narration and other extradiegetic sounds (a piano, children’s laughter), creating a real-time fiction that depends on and mystifies a listener’s assumptions about the relationship between sight and sound. Like the mp3, which “plays its listener[,] [the audio walk] is an attempt to mimic and, to some degree preempt, the embodied and unconscious dimension of human perception in the noisy, mixed-media environments of everyday life” (Sterne 835). Cardiff and Bures Miller’s audio walks use the mp3 as a vehicle – an extension of the human ear – for de-familiarizing the relationship between sight and sound: by layering sounds that are inherent to a particular environment with sounds that are alien to it, and by delivering those sounds in mp3 format, listeners are made aware of the discourses that inform their sonic environments, as well as of the artificiality of the mediums that transmit cultural information (i.e. digital media), a result that is achieved by interrupting our immersion in sound – by illustrating what it’s like to live entirely in sound. As R. Murray Schafer reminds us, “there are no earlids” (102).

Sterne states that the mp3 is a “container technology,” imbued with “a whole philosophy of audition and a praxeology of listening” (Sterne 827-28). The audio walk, like the mp3, compresses information (historical, social, cultural), trims the fat, and hands over a narrative, in a “tactile form of embodiment [that] is the requirement and result of digital audio” (827). Instead of being a meaning-making process, listening is reduced to a motor function: our ears are plugged and we are given a story in place of an explanation – sound determines experience, and meaning is disguised by content. The listener is given the illusion that he or she is an active participant in meaning-making, but this is a metaphor: the listener is a product of digital media and the codified discourses that mediate our understanding of the world through which we move.

By way of departure, and to complicate my assessment up to this point, please watch this six-minute excerpt from a 2012 remake of “Forest Walk,” renamed “FOREST (for a thousand years),” created for Documenta 13, a contemporary art exhibition in Kassel, Germany. No, the people in the video are not a part of the installation. Nor are they wax sculptures. They’re the participants. On Thursday, I’ll discuss Cardiff and Bures Miller’s use of video, McLuhan’s idea of “hot” and “cold” media, and sound as event.

(Again, headphones are recommended).

Works Cited

Cardiff, Janet. “Taking Pictures.” 2000. Janet Cardiff/George Bures Miller. Web. 11 Nov. 2014. mp3.

Cardiff, Janet and George Bures Miller. “FOREST (for a thousand years).” Online video clip. YouTube. YouTube, 28 June 2012. Web. 11 Nov. 2014.

McLuhan, Marshall. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1994. Print.

Nancy, Jean-Luc. Listening. Trans. Charlotte Mandell. New York: Fordham University Press, 2007. Print.

Schafer, R. Murray. “The Soundscape.” The Sound Studies Reader. Ed. Jonathan Sterne. New York: Routledge, 2012. Print.

Steiner, Rochelle. “Taking Pictures.” Janet Cardiff/George Bures Miller. n.p. n.d. Web. 11 Nov. 2014.

Sterne, Jonathan. “MP3 as Cultural Artifact.” New Media & Society 8.5 (2008): 825-42. Web.

“Walks.” Janet Cardiff/George Bures Miller. n.p. n.d. Web. 11 Nov. 2014.

The post Thinking sound and content through audio walks appeared first on &.

]]>