Digital Tools and the Audio Archive: The Edge of Meaning

Reading is not just about taking time and thinking time, it is also a deeply visual experience

— Andrew Piper

Why, in the case of the ear, is their withdrawal and turning inward, a making resonant, but, in the case of the eye, there is manifestation and display, a making evident?

— Jean-Luc Nancy

Since 2013, I’ve been working with SpokenWeb, a digital sound archive that features recordings from a poetry reading series that took place at Sir George Williams University (now Concordia) between 1966 and 1974. This project is invested in discerning “the poetry series” by investigating tools to facilitate critical engagement with recorded poetry recitation and performance — for reading sound. Listening (another form of reading) is a technologically informed activity, culturally rehearsed and historically specific, “always simultaneously a practice of visual interpretation” (Piper 388). How we listen is determined by the tools through which sound is transmitted. These tools control what we read and how we interpret it. While the SGWU Poetry Series is ripe with cultural, institutional, and literary history, as well as with the material, convivial, and circulatory implications of re-presenting archived audio recordings in a digital setting, not all of these facets are available for investigation.

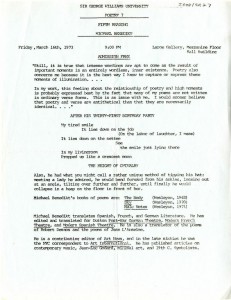

Here’s Roy Kiyooka, one of the Poetry Series organizers, introducing Muriel Rukeyser in 1969:

And here’s Jason Camlot, SpokenWeb’s principle investigator, speaking about the recordings themselves in 2012 and how they became, to borrow from Moretti, “a way to ‘open up’ [one particular sphere of] literary history” (227):

I want to highlight Camlot’s refrain – that is, where he refers to the collection of reel-to-reel tapes, once digitized, as “a perfectly useless archive.” To be sure, Camlot’s discovery was major, as was the work of Concordia University’s Records Management and Archives personnel, who catalogued and preserved the tapes, which are by nature inching toward obsolescence (a point to which I will return): a collection of over 80 sound recordings from a Canadian poetry series featuring some of the most important figures in North American poetry, which took place amidst institutional growing pains, cultural transformations, and an uncertainty surrounding the identity of Canadian literature. Here is the SGW Poetry Series in (always partial) media/historical context:

- Readings were held in one of three locations in the newly constructed Hall Building (Art Gallery, Basement Theatre, H-110).

- Readings took place on Thursday, Friday, or Saturday evenings (a few exceptions).

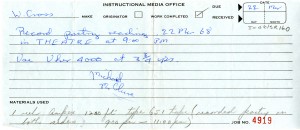

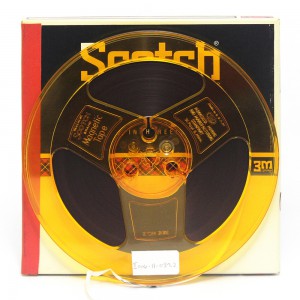

- Many of the earlier readings were captured using a Uher 4000 Report-L reel-to-reel tape recorder; the later ones, a Crown 800.

- Recordings were made on either 7” or 5” reels, at speeds ranging from 3 ¾ to 7 ½ IPS (inches per second).

- Many readings required more than one reel.

- Many of the reels were edited before Camlot discovered them.

- Recordings were originally commissioned by SGWU’s Instructional Media Office; later, the AV department.

- Audio-visual wiring in the Hall Building made it possible for the readings to be recorded remotely.

- Often, poets were escorted from the airport and taken for supper before their reading.

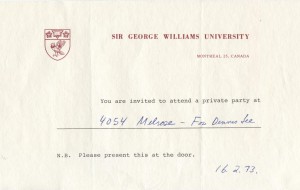

- There were poet parties after many of the readings – but only those lucky enough to receive one of the handwritten invitations disseminated during a poet’s performance were allowed to attend.

This context is directly related to Camlot’s refrain and my role as a digital archivist/curator. It also maps nicely onto Moretti’s “Slaughterhouse of Literature” (the clues!) and inspires larger questions surrounding ideas of representation, authenticity, presence and absence in relation to how we “read” documentary sound material. The series tapes were a perfectly useless archive because they were inert documentary material: unknown speakers speaking to unknown audiences on unknown dates in unknown locations. Put another way, the series couldn’t be visualized. It couldn’t be discerned. It wasn’t available as an object of study. The SpokenWeb project can be “seen” as a visualization of documentary sound material. Again, I nod to the good fine folks at ConU’s Records Management and Archives, who, by cataloguing, preserving, and digitizing the series tapes (not to mention their ongoing collaborative efforts, which I will allude to in a moment), have built a material platform upon which the site could be constructed and maintained. It is not the archivist’s job to provide context. It’s ours – a task that, again, would be much more difficult without the archivists’ hard work and guidance, for it is within the archive itself that most of our clues have been (and continue to be) uncovered:

- back issues of The Georgian, which contain press releases that provide dates, times, locations, reviews and so forth:

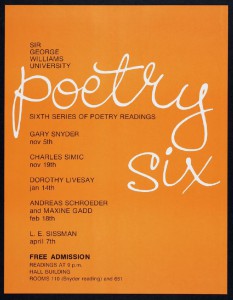

- event posters illustrating how the series was divided over its nine year run (i.e. Poetry Six, 1971-72 academic year), an alternate way to visualize the series over time:

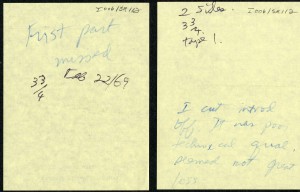

- the tape boxes themselves, which often included notes describing a tape’s content, such as which poems were read, or what materials were used to record the event:

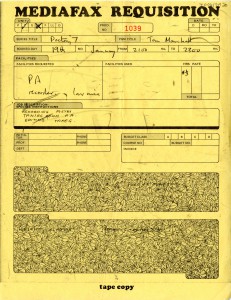

- and equipment requisition slips, which gave us some media perspective:

We have also incorporated an oral literary history element into the project by conducting interviews with some of the series organizers, poets who read in the series, audience members who attended the readings, and a technical operator who worked for SGWU during the series. However, by and large our context has been generated vis-à-vis archival research – through the accumulation of clues – “a ‘specific device’ of exceptional visibility” (Moretti 212) – an always ongoing classification of evidence, a seeing of sound.

Since the early stages of the SpokenWeb project there have been suspicions about comprehensiveness. Many of the clues we’ve uncovered point to date, time and location conflicts (information overlaps, omissions, and contradictions). There is even a Georgian press release that suggests the series did not in fact come to an end in 1974. There is also a gap in recordings between 1973 (in which there are zero) and 1974 (in which there are two) that further suggests (a) that some readings were not recorded, or (b) that they were recorded but for whatever reason were not included in the collection that Camlot discovered in the Chair’s office in 1999.

I want to bookmark a few questions. How should we think about the ways in which representation affects the status of cultural objects? These ‘unrepresented’ readings are unseen and unheard (they are catalogue numbers for tapes in small boxes in big boxes in a building in a city) but are they any less ‘present’ than those that are visible/audible? Are they any more authentic? What is a sound recording’s temporal status? How can we pin something down when it is superimposed in time?

Last week, while combing a section of Concordia’s AV Database (a real treat to navigate), I stumbled upon a familiar name, one that I had seen twice a few months earlier, first on a 1973 “mediafax requisition” slip, and second on a 1973 press release form. That name was Tom Marshall.

I pulled up the press release form to crosscheck the information. It was a match. The recording existed. Tom Marshall was stirring. His status was changing. At the bottom of the press release form there is a “Subsequent Readings” header, under which there are two additional names – Dennis Lee and Michael Benedikt. These names were also familiar. I seemed to remember having seen Lee’s name on one of the infamous after-party invitation slips, and having seen Benedikt’s on one of George Bowering’s “propaganda sheets” (the typewritten and manually disseminated equivalent of a press release form).

I went through my archival scans, found these artifacts, and compared the names and dates with those from the AV database. Also a match.

That day, I uncovered 20-30 recordings between 1969 and 1975, many of which I’d suspected, others featuring poets who are familiar but hitherto unrelated to the series. I had one major question: how could so many recordings have been left undiscovered for so long? They weren’t exactly hiding. So why had they not been digitized? I sent an email to Archivist and Records Officer Vincent Oulette, and received an answer: acetate.

The Poetry Series recordings were made using two different kinds of magnetic tape: acetate and polyester. Due to a lack of financial resources when the tapes were commissioned for digitization, priority was given to the acetate reels, which were (rightly) considered to be more in ‘danger’ of obsolescence than the polyester tapes. Therefore, it can no longer be assumed that the series tapes were digitized systematically – the digitization project was one of material preservation, not cultural posterity. Nevertheless, the reproduced voices of Lee, Marshall, Benedikt and a gang of other poets have been heard – and they are perfectly useless. It’s the SpokenWeb team’s task to stitch them into the SGWU Poetry Series fabric – “generated by clues—by their absence, presence, necessity, [and] visibility” (Moretti 217) – whereby we might “[turn] the story into something more than the sum of its parts: a structure” (218).

Works Cited

——- “Beyond the Text: Literary Archives in the 21st Century.” Yale University. Beinecke Library, New Haven, CT. April 2013. MP3. Panel discussion.

Kiyooka, Roy. “Phyllis Webb at SGW, 1966 (with Gwendolyn MaCewen).” SpokenWeb, 2010. Mp3. Web. 1 Sept. 2014.

Moretti, Franco. “The Slaughterhouse of Literature.” MLQ: Modern Language Quarterly 6.1 (March 2000): 207-227. Print.

Nancy, Jean-Luc. Listening. New York: Fordham University Press, 2007. Print.

Piper, Andrew. “Reading’s Refrain: From Bibliography to Topology.” English Literary History 80 (2013): 373-399. Print.

SpokenWeb. Concordia University. 2010. Web. 1 Sept. 2014.