From diagram to cryptogram, and the future of sense-making in the humanities

Last April, Toronto Star editor Jordan Himelfarb stumbled upon and eventually cracked the case of the Weldon code. According to Himelfarb’s research, a total of 20 coded messages have been uncovered between the pages of books at Western University’s Weldon Library over the course of the last two years, with each note, printed in a custom alphabet, accompanied by a physical item/trinket and the image of a household object, and stamped with the URL to a dead-end blog (000xyz.blog.ca).

It took Himelfarb less than a week to solve a mystery that for months confounded the Internet, one obsessive economist, a good-humoured Egyptologist, an enthusiastic library security guard, and a handful of (bored?) linguists and cryptographers. A simple Google search of the 000xyz blog owner’s username, “Sculpture 2.0,” turned up information about an art movement known as social sculpture, putting Himelfarb on the trail of one Kelly Jazvac who had previously taught at Western. The meeting with Jazvac revealed the notes to be part of an art project, the imaginative work of an undergraduate student. And ultimately, while decodable, the messages were meaningless.

And yet, Himelfarb wraps up the piece with vaguely optimistic and very humanistic conclusions about his experience investigating the so-called mystery of the Weldon code:

Mike Moffatt, the Weldon security guard and I, and the still-growing group of others around the world were drawn in by these objects of rare wonder. Bound by shared curiosity, we did something essentially human: We gathered in old spaces of inquiry and created new ones, and together searched for meaning. Forget what the code of the Weldon letters says; look at the beautiful thing it did.

It’s probably safe to surmise that the “beautiful thing” Himelfarb is referring to is the strange and otherwise unlikely collective of individuals who were brought together under the spell of an unknown language and the brief alternate reality this alien form opened up within the familiar silence of the library and its graves of knowledge. And the mysterious notes did so by failing to communicate anything: by mutilating expectations of content and readability, doing something instead through the untranslatability or unsayability of their cryptic form. Plumbing the depths of the unknown and coming out the other end with tranquilizing musings about the journey but few definitive answers is indeed a very human thing to do. At the close of “The Slaughterhouse of Literature,” Moretti operates under a similar state of obstinacy in the face of a failure to reveal realities without conflating structures and processes of discovery when contemplating the tautology of his research project. Sure the methodology was flawed and incomplete (it always is) but what diagrammatic methods like the tree graph offer is the possibility to re-inscribe all the nothings, in such a way that while “literary history could be different from what it is” but isn’t and all the nothings are still nothings and the Weldon notes still mean nothing new formal constellations hint at the always-present invisible potentialities in the transition from states of multiplicity to modes of representation, even if what is brought into view are simply new territories of connection within which to consider otherwise trivial objects (227).

That’s a very Badiouian thing to say, obviously, but as Piper reminds us, namely by referencing Badiou’s ontological mathemes, a certain measure of diagrammatic and/or cryptographic literacy has always had a place in literary studies well before the rise of the digital age. Harder to forget still is how contentious the alliance between literary studies and technical/mathematical systems of logic has always been. As Alan Sokal and Jean Bricmont tried to argue in Fashionable Nonsense: Postmodern Intellectuals’ Abuse of Science (1998) the suspicion persists that literary theory’s appropriation of algebraic and now computational modes of thinking works to aesthetically legitimize the field and the value of its interpretations in the world. Then again, it took a journalist with a background in philosophy to decipher the gibberish behind a set of glyphs, to see “the significance of non-significance” of the code-breaking process and elevate a little story with the sort of mysticism that makes us want to look deeper into obscure spaces (Piper 395).

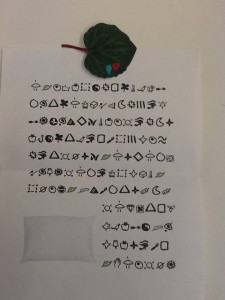

Having said that, we can consider another recent (and in this case, or thus far, annual) cryptological event that forces us to ask more serious questions about the future of sense-making in the humanities and the future of humanists poorly versed in cryptologic. The Cicada 3301 puzzles, a series of nested encryptions that usually begin with a single image, mysteriously started appearing online with the explicit intention of seeking out “intelligent individuals” with a host of specialized skills related to cryptography. Here, for example, is the twitter image that launched this year’s Cicada puzzle:

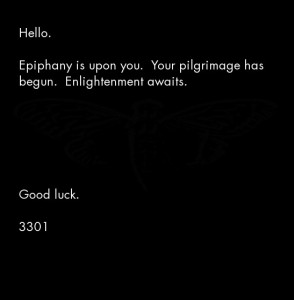

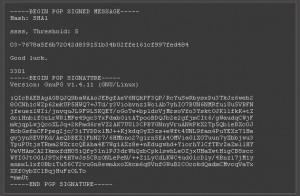

And here is the code yielded after the image was stenographically processed through a program called outguess:

No one knows who or what is behind Cicada, nor what solving the puzzle uncovers, and while I certainly have no hope of finding any of this out there are naturally speculations that this is an elaborate recruitment game organized by security agencies. Of interest, however, is that Cicada is basically a digital onion concealed mostly in references to literature, art, and philosophy–code games instead of language games whose deep readings necessitate specialized knowledge that my recent experience working on the Dracula database taught me I do not possess. Considering the Cicada puzzles alongside the Weldon incident brings up mixed feelings about Piper’s observation (warning even) that there is an undeniable “push against the sequestration of numbers from language” (388). There is a problematic romanticization of the human project behind Himelfarb’s final insights (which is arguably also reflected in the occultist draw of the Cicada puzzle) that nonetheless reinscribes the truth-values, however inauthentic but perhaps needed, that humanist impulses bring to the table. At the same time, reminders come along that there is much more going on in the darkness and the blindness of those readings. What matters more perhaps is asking how this conversation is mutually redefining both the status of literary texts and the status of code as non-literary.

References:

Himelfarb, Jordan. “I cracked the code at the Western University library.” The Toronto Star 5 April 2014.

Moretti, Franco. “The Slaughterhouse of Literature.” MLQ: Modern Language Quarterly 61.1 (2000): 207-227.

Piper, Andrew. “Reading’s Refrain: From Bibliography to Topology.” ELH 80 (2013): 373-399.