Boot Camp: “Composing a Backward Essay;” or: “Making Deformative Poetics with My Computer;” or: “How to Completely Erase Your Hard Drive;” or: “Sabotaging Conclusions”

The titles always come last. Before that, comes the final warning:

This essay irrecoverably destroys data!

Eulogy: I regard the wasted corpse that used to be my computer. Once glitched beyond repair, now a useless assemblage of titanium, plastic, wire and glass. Many of its sensual qualities remain: the keys that have embraced the impact of my fingers; the dust embedded in the touch pad; the infected circuit board; the faulty battery-cord connection. Finding myself strangely reluctant to part with the thing, I slide it under my bookshelf… R.I.P.

Afterword: The viral infection that affected the circuit-board of my computer has left us both in the quiet of cultural removal. Aside from what remains in my notebook, all information is lost. Although most of the essays and drafts that I have written are stored in Google’s online database, now they are left vulnerable to the randomness and chance of the internet. Meanwhile, free of network responsibilities, I will draw you a picture to illustrate where I’m coming from. But without my digital processor, I have no option but to interface via a photograph of the written page:

Working Backward: What follows is a retrospect of my findings. This essay is composed backward — from the erasure of my computer’s hard drive and back through the processes that demanded this action. Data analysis will begin with results, but works through regression toward hypotheses and questions. This deformance amounts to nothing obvious. But in moving away from conclusions, destruction opens up creative potentialities. Since this experimental essayism necessarily involves the instrument of composition (my computer), this counter-linear method is an intimate reminiscence on our collaborative history.

Conclusions: Embracing the death of my computer, I begin to envisage new methods of occupying an unproductive stillness in the centre of digital media and cyberactivism. In lieu of generating and storing information, some of these goals may even lead toward what Donato Mancini describes as the production of “motivated blockages in urban flows, and/or diversion of such flows into ambivalent alterities” (141). To cultivate “a simmering threat of ambush, sedition, or defiant anti-productivity” (141), however, depends on knowing the instruments by which these activities will be realized.

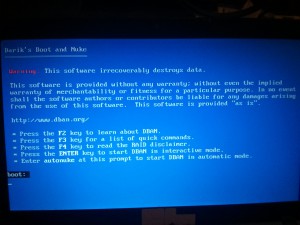

The Final Step: Before throwing the apparatus into an electronic waste pile, a friend advised me to ensure that all private content would be forever eradicated from my computer’s hard drive. Typing “how to completely erase my hard drive,” Wikihow and Google both lead me to Darik’s Boot and Nuke website. I downloaded the program, and prepared to wipe the computer’s hard drive clean. After burning the program to a USB flashdrive, I commenced the process of complete and permanent deletion of content. Since my desire was to erase everything with no chance of retrieval, I was not dissuaded when the screen (captured below via my smartphone) appeared. Upon uttering my laptop’s final rites, I hit enter and watched the death-dealing, final cleanse run its course…

A Meditation on Viruses: Maybe two months prior, I had taken my computer to specialist to have the virus(es) removed. But, perhaps two weeks later, the problem reappeared, and soon thereafter the system became completely defunct. Did this infectious susceptibility have something to do with my own corruptive habits? When using the internet, I was always careful to avoid downloading suspicious files. And I almost never looked a porn… What insidious agent in my PC this lugubriousness and counter-productivity? What perversity was behind all the time I wasted waiting for pages to load? How could I get a complete and comprehensive analysis of the virus (or viruses) that affected the operative organs of my PC?

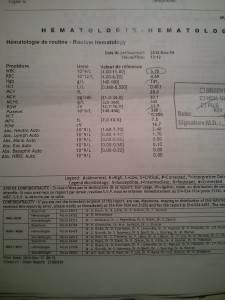

Countermeasures: When I had my blood tested a couple of weeks ago, a week later my doctor provided me the following account. Explaining any questions I had about the data, the Doctor’s analysis was helpful and informative:

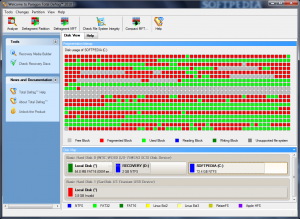

What does a viral scan of computing systems look like? In hopes of securing a better view of my computer’s inner workings, I downloaded a Disk Defragmenter, and ran a scan. Unfortunately, I was completely bewildered by the results. Defragging scan results will come out something the image below. But without technical explanation, I still had no conception of the bugs, rabbits, worms, germs, and other contagions that had found home in my computer’s operating system:

Auto-Sabotage? My computer’s propensity toward re-fragmenting and re-infecting itself may inform us about radical poetics and poetics. Mancini calls poetry “metaphysical recycling,” an active re-making of what is out there. Brian Massumi describes the creative potentiality that emerges from deviation and digression (18). My computer’s being almost useless, but still functioning, might even provide an example of radical politics. In a work entitled Sabotage, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn describes how “the fine thread of deviation” allows for powerful but subtle activism that breaks the juncture point of machinery. And Evan Calder Williams describes how the withdrawal of efficiency, the interference with standards of “quality,” and the rendering of things to be useless can be powerfully disruptive forces within the modes of capitalist production.

Report Abuse? For more than a year I have been observing the gradual depletion in my computer’s capacity (or willingness) to function according to my administrative standards. As this tension has increased, new questions have arisen as to about whether or not my expectations of the machine were fair. Had I exploited the tool? What could explain this rebelliousness? The audio feedback, the sudden restarts, the noisy fan, the faulty battery pack — all these clues suggested more than just a brief albeit noisy disturbance, but a structural problem from within the mechanism. Perhaps my laptop was enacting its own version of what Johanna Drucker articulates as a “push against the logical constraints imposed by digital media” (22).

Nothing is worth preserving: Beginning to fear for the extended lives of my electronic documents, films, photos, and mp3s, I realized that I had few items that we useful or interesting. Aside from some of my “treasures” — easily replaced artifacts like Alejandro Jodorowsky’s Holy Mountain, a PDF of Walter Benjamin’s Illuminations, and Kate Bush’s complete discography — my computer only stored two items that I would never find again: 1) a very rare/bizarre self-portrait taken by an ex-lover as blood ran out of her nose (after Andrew W.K.); and 2) a recording of Omar Souleyman’s Dabke 2020: Folk and Pop Sounds of Syria (album I’ve not been able to find easily on the internet). For everything else, Google keeps safe all of my email correspondences, and I still have paper copies of all else I have written. Facebook keeps my photos; Grooveshark, my music. Perhaps — if only these online storage banks could be wiped out — we could start again from nothing.

On tossing my library: “Why save or collect anything?” In “Unpacking My Library,” Walter Benjamin writes that “[t]he most profound enchantment for the collector is the locking of individual items within a magic circle in which they are fixed as the final thrill, the thrill of acquisition, passes over them. Everything remembered and thought, everything conscious, becomes the pedestal, the frame, the base, the lock of his property” (60). Looking my own libraries, I am struck by the vast stores of useless junk. Here is nothing magical. Perhaps it is no wonder that my computer has become bored with tedium of lugging all this shit around. After a moment’s consideration, I elect that I will throw the whole library out.

Opening hypotheses and questions: Johanna Drucker draws our attention to the co-dependencies existing between scholars and the range of tools used in “the searching, storing, retrieving, classifying, and … visualizing data” (28). Although much scholarship in the Digital Humanities engages with norms, means and averages of quantifiable data, Drucker advocates studies in the exceptions, gaps, deviations, indeterminacies, and exceptions that are just as present. From a “grand perspective” I have sifted through the stores of material that has been saved on my personal computer, and am reminded of George Carlin’s claim that we have “too much stuff!” But then, everything tends to become more interesting when stuff doesn’t work for us anymore. Like Heidegger, I have become fascinated by moments when a tool reveals its unhandiness: “When we discover its unusability, the thing becomes conspicuous” (72). My computer’s immanent break-down has revealed a gap in my own scholarly process. When break-downs occur, broader questions are opened: “Who does our stuff work?” or: “According to whose standards are we operating?” and finally: “Why work at all?”

Citations:

Benjamin, Walter. “Unpacking My Library.” Illuminations. Trans. Harry Zohn. New York: Schocken Books, 1978. 59-68. Print.

Carlin, George. A Place For My Stuff. Atlantic Records, 1981. CD.

Darik’s Boot and Nuke. Blancco, 2014. Web. 4 December 2014.

Drucker, Johanna. “SpecLab: Digital Aesthetics and Projects in Speculative Computing.” Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2009. Web. 8 September 2014.

Flynn, Elizabeth Gurley. Sabotage: The Conscious Withdrawal of the Workers’ Efficiency. Chicago: I.I.W. Publishing Bureau, 1917. Web. 4 December 2014.

Heidegger, Martin. Being and Time. Trans. Joan Stambaugh. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2010. Print.

Massumi, Brian. Parables for the Virtual. Durham: Duke University Press, 2002. Print.

Williams, Evan Calder. Lecture on “Sabotage.” Concordia University. Montreal, QC. 14 November 2014.