Carpentry, Networks, and Munchkin Cthulhu

Munchkin Cthulhu is a game designed by Steve Jackson and illustrated by John Kovalic. The game is based on the works of H.P. Lovecraft. Ian Bogost writes, “One form of carpentry involves constructing artifacts that illustrate the perspective of objects” (109), so if Lovecraft’s written works can be considered the “object,” then the card game could be seen as the artifact constructed in relation to it. Not everyone who plays Munchkin Cthulhu has read Lovecraft, but the great thing is one does not have to know Lovecraft to play the game. Yet, if they ever do decide to read Lovecraft, the connection between the game and his writing takes on significance as how many authors have a monster named Cthulhu? Bogost says at “Urustar, designers recast and condense hundreds of pages of my books into playable pixel art” (110), and Steve Jackson performs the same sort of “carpentry” with Lovecraft in transforming his work into a playable game.

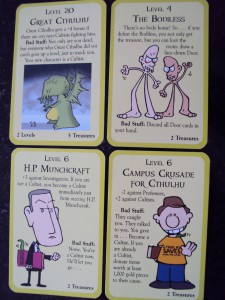

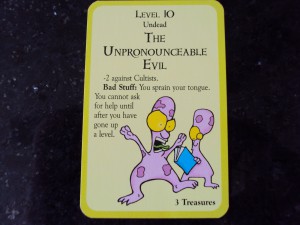

Munchkin Cthulhu has its own network; it has rules, a die, cards, and players. The rules state you can have between three to six players and everyone needs ten tokens. There are door cards, and treasure cards. Each player starts with two door and two treasure cards. When playing the game, one begins their turn by “opening a door” i.e. you pick a door card and the card dictates what you do. You can end up fighting a monster, they range in level from on to twenty. Some examples:

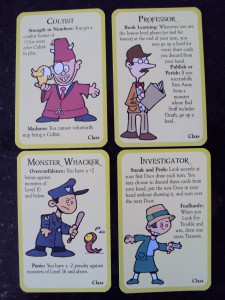

You can also pick a class card. If you choose to accept a class (all players start with “no class” – to the endless amusement of the game designers who “never get tired of that joke” (Game Rules 1)), some of your choices are:

If you pull a class card first on your turn, you have the choice to pick another card or, “look for trouble” – i.e. pull another door card, or fight a monster you have in your hand (you can hold up to five cards). The goal of the game is to be the first to reach level 10. You go up levels by beating monsters (mainly) or by using “Go up a level” cards. Your strength in battle is determined by your existing level (all players start at level 1), and added to your level is whatever treasure you have in play that gives you a bonus you can add to your level (these are displayed in front of you). Some examples of treasure:

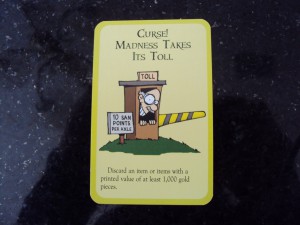

Thus, if you are a level one without any aid in the form of tentacles, cowls, or bumper stickers (among other interesting things), and you draw a level 10 monster, death is imminent. However, you have choices at this point. You can flee – which works only if you roll a 5 or 6, or you can ask for help from another player(s) (that is if they are willing to help you). If all players are level 1 with no help, then you take your chances and flee otherwise you all die. If the other player is in a position to help you, and is willing to, (because if you win the battle you gain a level and are that much closer to winning), they usually (at least in my family) demand treasure in exchange. Asking for help does not work when you are a level 9 and need to kill the monster for the win (you must kill a monster to win, you cannot use a “Go up a level card”). At this point everyone gangs up on you and you are pretty much doomed. Usually the next person at level 9 wins their battle because by now, everyone has exhausted their firepower on the previous potential winner. Here are some of the cards that can help or hinder you:

Through the game, Jackson embodies Bogost’s examples that “put theory into practice; [but] also represent practice as theory” and demonstrates that “writing is not the only method of engendering interest” (111). I have had the game for a while and all this time I never realized that Lovecraft is the creator of the monster Cthulhu until now. The game, and its monsters, generated an interest in Lovecraft’s works as a means to investigate the source of Jackson’s inspiration. Graham Harman writes that “no other writer is so perplexed by the gap between objects and the power of language to describe them, or between objects and the qualities they possess” as is H. P. Lovecraft. Yet Jackson takes Lovecraft’s ideas and creates something tangible and visible. We handle the cards and look at the pictures. The monster Cthulhu that Lovecraft never definitively describes is depicted on a card as “Great Cthulhu,” a level 20 monster. According to Harman,

Lovecraft’s major gift as a writer is his deliberate and skillful obstruction of all attempts to paraphrase him. No other writer gives us monsters and cities so difficult to describe that he can only hint at their anomalies. Not even Poe gives us such hesitant narrators, wavering so uncertainly as to whether their coming words can do justice to the unspeakable reality they confront (9-10).

Yet, as one can see from this card:

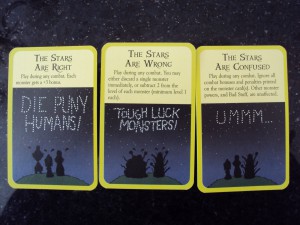

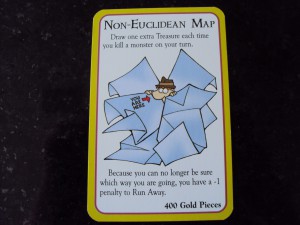

Jackson and Kovalic have come up with their own version of Lovecraft’s “unspeakable reality,” but, as Darren kindly pointed out, they have also transformed Lovecraft’s “horror” into something comic, thus inverting the original intent of his works. Jackson parodies Lovecraft’s ideas and the philosophical debate that surrounds his work. John Law devotes space in his article to the discussion of “Euclidian and Non-Euclidian Spaces” (95), but for Jackson Non-Euclidian spaces becomes:

Jackson takes a complex philosophical idea and turns it into something tangible and fun. If you draw this card, it is very useful within the game as treasure because it is not tied to a class, (some artifacts can only be used by certain classes so if you are not a cultist, for example, you cannot use an artifact usable only by a cultist), and the more treasure you have that you can use, the greater chance you have of winning the game. Also, throughout the game, if you accumulate treasure worth 1000 gold pieces, you can trade them in for a level (unless you are a level 9 of course). The great thing about Munchkin is that the player does not need to know what a Euclidean or Non-Euclidean space is to have fun. The player simply has to know how to use the card effectively.

However, chaos is the underlining rule of the game. There are always disputes over the rules or what a card really means or does and inevitably everyone thinks something different (usually to their advantage). Knowledge will not help you in these situations as “disputes should be settled by loud arguments among the players, with the owner of the game having the last word” (Game Rules 4). That would be me.

Works Cited

Bogost, Ian. “Carpentry.” Alien Phenomenology, or, What It’s Like to Be a Thing. Posthumanities. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota Press, 2012. 85-111. Print.

Harman, Graham. Selections from Weird Realism: Lovecraft and Philosophy. Winchester/Washington: Zero Books, 2012. Print.

Jackson, Steve. Munchkin Cthulhu Rules. 2007.

Law, John. “Objects and Spaces.” Theory, Culture & Society 19.5/6 (2002): 91-105.