Probe – There is no ending

Critique is never-ending. As Tony Bennett’s article shows, there is always room for critique, because there will always be additional angles from which a certain issue can be addressed. By way of example, Bennett argues that Franco Moretti’s model has “limits” (Bennett, 280), that there are “difficulties” related to its construction (285), that Moretti “throws in the towel too quickly here” (289) and “abandons his search for evolutionary continuities too quickly” (290), etc. etc. And Bennett’s criticism of Moretti is only one example (for others, see for instance Amir Khadem’s article “Annexing the unread: a close reading of ‘distant’ reading”). Furthermore, the critiques can be critiqued, not necessarily to defend the initial method under scrutiny (in this case Moretti’s) but to uncover the shortcomings and limits of the critiques themselves.

Is there, by the way, something like uncritical analysis? Is everything “critical”, and because of this omnipresence of critique, it had to run out of steam at some point, as Bruno Latour says? Why, in fact, would we, academics, critique all the time? What’s our objective? To succeed with our next grant application? Get another publication? Ian Bogost argues somewhat cynically that publications “serve as professional endorsement rather than as a process by which works are made public” (Bogost, 88). Or are we, at least to some extent, really trying to make the world a better place? With all this in mind, I decided to be self-reflective and revisit a cultural object that I produced myself: my first probe.

My probe – An archeology of vernacular photography

I think we can agree that a probe is a cultural object. In fact, I would say that it’s not just an ‘object’ but rather a ‘thing’, as Latour says by referring to Heidegger. The probe is not an object of science and technology but has richer and more complicated qualities, and I care about it in a different way than for instance about an industrially produced object (Latour, 233). In this sense, I hope that Heidegger would agree that my probe does not deserve the label ‘Gegenstand’ but that it can be a ‘Ding’.

Latour also suggests that we should turn from matters of fact to matters of concern. I read this as an advice that we should care about the things – and not only about the objects – around us, about what we are doing, about what we are critiquing. Therefore, playing the hypercritical critic inspired by Heidegger and Latour, I translate Darren’s instructions to write our probes on a “cultural object” into writing them on a “cultural object or thing”.

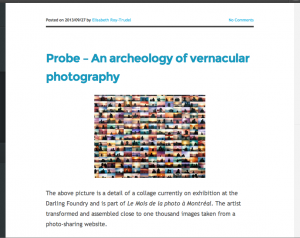

In my probe An Archeology of Vernacular Photography, I looked at the collage Sunset Portraits. How did I – critically – analyze this artwork? While I mostly relied on Foucault, I could probably have developed a much stronger argument by including more recent theories that build on Foucault and have been applied more specifically to media studies. I am thinking, for instance, of Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht’s notion of “materialities of communication” (Gumbrecht, 6-8) and his call for a focus on the “production of presence” that emphasizes the tangibility of all forms of communication (Gumbrecht, 17). My perspective would certainly have been different, and I could have pushed my observation both of the artwork Sunset Portraits and of the operation of posting and sharing of images on Flickr as material meaning-constituting forms of communication.

I could have relied on a number of other methods that we discussed over the term. I am thinking, for instance, of abstract visualization methods, such as those suggested by Franco Moretti, that can increase our understanding of complex objects and underlying structures (Moretti, “Network Theory: Plot Analysis”, 4). Paraphrasing Moretti, I could say that any field isn’t a sum of individual cases: “it’s a collective system, that should be grasped as such, as a whole” (Moretti, “Graphs, Maps and Trees, Abstract Models for Literary History – 1”, 68). This sounds a bit like a basic insight from a Durkheimian sociology, but looking at the system certainly changes the nature of the question. Maps, graphs and diagrams can reveal generalities, different dimensions, and implicit connections; they point to problems that weren’t seen before. By way of example, I asked in my probe how and why the individual images representing sunset portraits relate to each other. Well, wouldn’t a diagram revealing the locations from which part of the world the images were posted on Flickr bring us to ask a whole range of additional questions? Or a graph visualizing the activity on Flickr both over time and in space? We can speculate, for instance, that a diagram would have revealed important clusters, for instance around urban centers in North America and Europe. This might have raised questions relating to the accessibility of information technology and the distribution of wealth and whether these are factors that contribute to what Penelope Umbrico, the artist who created Sunset Portraits, sees as a loss of subjectivity and individuality.

But isn’t Umbrico herself overly concerned with a phenomenon that is created and sustained by a privileged minority on the planet? If I scratched a little bit on the surface of the gender dimension when I asked whether the heterosexual couple was the ideal subject for a sunset portrait, there is really not much of a feminist analysis here. Feminist theory, postcolonial studies and critical race theory would call attention to such issues that have certainly been debated in the field of visual culture but perhaps less so in digital humanities. The question why the digital humanities are “so white” has of course been asked, for instance by Tara McPherson. She argues that “[c]ode and race are deeply intertwined” and that we “must develop common languages that link the study of code and culture”. Similarly, Amy E. Earhart reminds us that “[w]e need to examine the canon that we, as digital humanists, are constructing, a canon that skews toward traditional texts and excludes crucial work by women, people of color, and the GLBTQ community.” In short, power relations are always a determining, although often overlooked, factor. A number of approaches and methods that have been developed in other fields are therefore useful to ask important questions relating to digital humanities. Critique and methods of critiquing are not and should not be confined to specific disciplines. At the same time, a field can develop a specific methodology that is also useful in other fields, thus making a much more significant contribution. Alan Liu concludes in his article about the future of criticism in the humanities that the digital humanities can and should contribute to (cultural) criticism more generally by rethinking the idea of instrumentality, overcoming the artificial divide between the humanities and the fields of science, technology, engineering and mathematics.

Going back to the critique of my first probe, I could also have analyzed Umbrico’s work through Bogost’s notion of carpentry. Art is arguably a form of carpentry, and Umbrico clearly constructs artifacts as a philosophical practice (Bogost, 92). In a few words, she makes things that explain how things relate to each other. I am not too sure what insight I would have gained from this, or from actor-network theory, or from fucking up Sunset Portraits, but I think that’s the point! Although possibly scary and challenging, unexpected results of an analysis can be much more pertinent and revealing than those we anticipate when choosing our objects of study and methods. And maybe I would have realized that some of the approaches that we have looked at during the term are simply not suitable to my object or to the way I relate to it (which would also have been a useful finding).

In sum, I didn’t even attempt a relatively close reading of the images posted on Flickr or an interpretation of Umbrico’s work (by the way, such a close reading would also have been useful – after all, distant reading and close reading are complementary). And yet, since my approach consisted primarily in a discourse analysis, I foreclosed a number of insights that I could have gained from other non-hermeneutical distant reading methods. Should I have explained why I didn’t push my analysis further in any of these directions? Of course, the idea was to focus on discourse analysis for that specific class. My point here is that since every piece of writing reflects biases and is obviously and inherently limited in many ways, shouldn’t we always try to make explicit at least the most important biases and limitations and explain the reasons of our respective choices? The danger is that writing becomes equivalent to making disclaimers, which is not constructive either. But addressing lines of critique that we can already anticipate will allow the discussion to move on faster and in possibly more diverse ways.

Critique is inevitable. That being said, I like the idea that we can all contribute to making it more constructive. And, as Foucault cautioned, we can – and should – think about everything! Being critical about our own critical analysis is part of it, even if we don’t know exactly where this will take us. In other words, I don’t believe in any sort of methodological or critique-related closure or finality – it’s never finished.

Now, “because writing is only one form of being” and is too heavily focused on argumentation (Bogost, 90-91), I’ll stop here and do something else now. Perhaps some carpentry.

Works cited:

Bennett, Tony. “Counting and Seeing the Social Action of Literary Form: Franco Moretti and the Sociology of Literature.” Cultural Sociology 3 (July 2009): 277–297.

Bogost, Ian. “Carpentry.” Alien Phenomenology, or, What It’s Like to Be a Thing. Posthumanities. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012. Print. 85–111.

Earhart, Amy E. “Can Information Be Unfettered? Race and the New Digital Humanities Canon” in Matthew K. Gold, ed, Debates in the Digital Humanities, 2012, online: http://dhdebates.gc.cuny.edu/debates/text/16.

Gumbrecht, Hans Ulrich. “Materialities/The Nonhermeneutic/Presence: An Anecdotal Account of Epistemological Shifts.” Production of Presence: What Meaning Cannot Convey. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 2004. 1–20. Print.

Khadem, Amir. “Annexing the unread: a close reading of ‘distant’ reading”. Neohelicon 39:2 (2012): 409-21.

Latour, Bruno. “Why Has Critique Run out of Steam? From Matters of Fact to Matters of Concern.” Critical Inquiry 30 (Winter 2004): 225–48.

Liu, Alan. “Where is Cultural Criticism in the Digital Humanities?” Debates in the Digital Humanities. Ed. Matthew K. Gold. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012. 490–509. http://dhdebates.gc.cuny.edu/debates/text/20.

McPherson, Tara. “Why Are the Digital Humanities So White?, or, Thinking the Histories of Race and Computation” in Matthew K. Gold, ed, Debates in the Digital Humanities, 2012, online: http://dhdebates.gc.cuny.edu/debates/text/29.

Moretti, Franco. “GRAPHS, MAPS, TREES: Abstract Models for Literary History — 1”. New Left Review 24 (Nov-Dec 2003): 67–93.

—. “Network Theory, Plot Analysis.” Literary Lab Pamphlet 2. May 1, 2011. [Orig. pub. New Left Review 68, March-April 2011]. http://litlab.stanford.edu/LiteraryLabPamphlet2.pdf.