The Artist as Aggregator : The Listening Post

How is an author now a postindustrial producer? What are the aesthetics of encoded or structured discourse or, as I will term it, of postindustrial dematerialization? How is it possible for writers or artists to create in such a medium? [1]

These are questions posed by Liu in “Transcendental Data: Toward a Cultural History and Aesthetics of the New Encoded Discourse”. One of the crucial characteristics of this structured discourse of dematerialization that Liu points to is the separation of content from presentation. Content is separated out into a series of mobile, atomized chunks amenable to algorithmic processing. The form in which this content is presented is conceptualized as an empty container, a blank space, a ‘data pour’ that content can dynamically fill up. This separation of content and form is the underlying ideology of what he posits as discourse network 2000, and he uses XML as an example of a technology that enables the aggregation of atomized content between human and machine agents.

Echoing the questions posed by Liu, how can artists and authors create in this kind of aggregated environment? What happens when artists create based on the structured choices provided by software? Can artists use technological tools to critique the very structured discourse that they enable, or does art become as Matthew Fuller would say an ‘engineering problem’[2]?

I would like to open up these questions by discussing an installation work called Listening Post created in 2001 by media artist Ben Rubin and Mark Hansen, a joint professor at UCLA in Statistics and Design Media Arts.

Listening Post is an installation made up of a display wall with 231 small digital screens. It is described as “a ‘dynamic portrait’ of online communication, displaying uncensored fragments of text, sampled in real-time. It is divided into seven separate ‘scenes’ akin to movements in a symphony. Each scene has its own ‘internal logic’, sifting, filtering and ordering the text fragments in different ways” [3]. In each ‘scene’, mined text is streamed across screens to make up different visual patterns. The patterns are pre-determined, but the streamed text is mined in real-time from unrestricted internet chatrooms, bulletin boards and other online forums based on parameters set by the artists. Even though the pattern of each scene remains the same, visually the work changes depending on the text that appears each time. The work is accompanied by an ambient soundtrack that responds to shifts in the data streams and computerized voices which read selected texts. The work is algorithmic and generative; it incorporates “elements of chance and randomness common to experimental art from the early 20th century to the present day”[4]. The experience of the work will never be the same twice as its context is provided by the thousands of real-time discussions happening online at any given moment.

It’s like writing a novel on index cards and throwing them out of an airplane at 30,000 feet. When the cards land, somehow they line up in the right order, or—even more uncannily—in someone else’s searched, sampled, remixed, summarized, and aggregated order. (Liu, 58)

There is an aggregated order at work in Listening Post, based on algorithms designed by its creators. Perhaps it is not a very meaningful order although the temptation to read order into the randomly generated texts and their patterning in proximity to each other is unavoidable.

Does a work like this bring any critical sensitivity to the aesthetics of aggregation? I think that the artistic strategy used by these artists provides some ways of thinking through the questions posed in this probe. In many ways this work uncovers the underlying material and political dimensions of aggregation in digital networks.

There is the obvious reference to surveillance, and the practice of mining and sampling data establishes links to other forms of control associated with the history of data aggregation, namely population statistics and demographics. The algorithmic aggregation of text is not used to produce anything meaningful; does it thereby undermine the ideologies of work and productivity behind the technologies it uses? There is no end product here. The text blocks scroll into view, some are read, and they all disappear.

The audio dimension of the work has a cheesy corporate quality; the generated soundtrack and the computerized voices reading over it are reminiscent of a certain genre of technology advertising, for example:

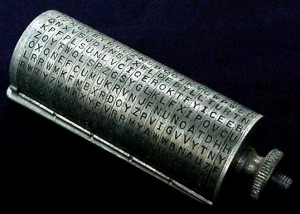

The visual dimension of the work makes reference to other forms of communications and advertising that use scrolling text. The scrolling text also reminds me of early forms of cryptography such as ciphers, which when you think about it not so different from how a computer understands text – as a sequence of individual letters to be encoded. The audio and visual references in the work and the real-time algorithmic processing of text evoke the intertwined military and commercial history of computing and networks.

Jefferson Cipher. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jefferson_disk

Interestingly, a version of this same work was commissioned by the New York Times in 2007. Moveable Type is installed in the lobby of the Times building. It uses the same principles to aggregate real-time texts from the day’s newspaper, online visitor comments and archival materials dating back to 1851. It is accompanied by a soundtrack of typewriting, the marker of a past era of productivity and work.

In both Moveable Type and Listening Post there is an attempt to capture something about our networked activities and identities, to return atomized pieces of content that will challenge our perceptions of this environment. Listening Post does this in a counter-intuitive way by returning noise, instantaneous accidental fragments of the internet. Maybe the metaphor of listening is an interesting choice that offers a different framework for thinking about data. Can the abandonment of signal for noise subvert structured discourse? Perhaps Listening Post does so by providing an alternate means of representation of aggregated human activity, giving access to large quantities of raw textual data; a form of data sublime? Brett Stalbaum has argued that the sublime aesthetic may offer an alternative means of knowing ourselves through data. In contrast to the predominant aesthetic of data representation through reduction and simplification, access to large quantities of raw unmediated data could allow communities to “take democratic control of their own data interpretation in a way that best balances their exposure to quantities of data against their need to reduce it to useful information”[5].

Liu concludes by asking “what experience of the structurally unknowable can still be conveyed in structured media of knowledge” and looks to the arts for a potential solution. Whether or not we can have hope in the unknown of access to raw data as an empowering force, the artist as algorithmic aggregator might provide some means of exploring and deforming the affordances of digital text.

1. Liu, Alan. “Transcendental Data: Toward a Cultural History and Aesthetics of the New Encoded Discourse.” Critical Inquiry 31 (Autumn 2004): 49-84.

2. Fuller, Matthew. “It Looks Like You’re Writing a Letter: Microsoft Word.” Behind the Blip: Essays on the Culture of Software. Brooklyn: autonomedia, 2003. 137-165.

3. Description from the Science Museum website. http://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/smap/collection_index/mark_hansen_ben_rubin_listening_post.aspx

4. Redler, Hannah. “Monument to the present – the sound of 100,000 people chatting.” London: London Science Museum, 2008. Curatorial Statement. http://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/smap/collection_index/mark_hansen_ben_rubin_listening_post.aspx

5. Stalbaum, Brett. “An Interpretive Framework for Contemporary Database Practice in the Arts.” Presented at the College Art Association 94th annual conference, Boston MA, 2004. http://www.paintersflat.net/database_interpret.html