Memorializing Technologies

Theoretical Framework

Recently, many academics have tasked themselves with interrogating how technology has been studied with respect to its relationship with culture and media. Authors such as Bernhard Siegert, Jonathan Sterne, Sybille Krämer, and Horst Bredekamp criticize the characterization of technology as a sphere separated from that of ‘culture’ (a term itself defined by an outmoded or out-of-fashion hermeneutic perspective or focus), and the conception of media technologies as objects necessarily grounded in ‘mass culture’ (a view produced largely by postwar interrogation of propaganda use, especially in European countries such as Germany). As Krämer writes, “‘Culture’ is no longer confined to what is enshrined in works, monuments, and documents in stable and statutory form.” (Krämer, 23)

Recently, many academics have tasked themselves with interrogating how technology has been studied with respect to its relationship with culture and media. Authors such as Bernhard Siegert, Jonathan Sterne, Sybille Krämer, and Horst Bredekamp criticize the characterization of technology as a sphere separated from that of ‘culture’ (a term itself defined by an outmoded or out-of-fashion hermeneutic perspective or focus), and the conception of media technologies as objects necessarily grounded in ‘mass culture’ (a view produced largely by postwar interrogation of propaganda use, especially in European countries such as Germany). As Krämer writes, “‘Culture’ is no longer confined to what is enshrined in works, monuments, and documents in stable and statutory form.” (Krämer, 23)

This reconsideration of how technology is viewed theoretically has led to a reinterpretation, or reforming, of many aspects of poststructuralist theories grounded in the notion of text-as-culture. Subsequently, the notion of Cultural Techniques has emerged, in an effort to bring technology into the cultural fold, so-to-speak, from its relatively isolated pedestal, or perhaps more appropriately, from the island to which it was once relegated. As Jonathan Sterne puts it, “technologies are crystallizations of socially organized action.” (Sterne, 367) This reconsideration allows technology to be studied as a part of culture, a sphere that interacts with culture, that both forms and is formed by it.

The theoretical realm of cultural technique conceives of technologies not as objects that are, simply or primarily, products created to fulfill a particular need or function. According to cultural technique, technologies are not simply physical objects designed and produced to fulfill a function for which there was previously no tool to perform. Instead, technologies function as symbolic components of actor-networks; they act as both objects and processes, occupying a dialectic influenced and generated by how they are used and how they influence the ways in which they are used. Technologies not only evolve, or are changed and modified by their use, but are incepted by ongoing processes of cultural actions that fall within the ‘realm of use’ that a given technology occupies. As Bernhard Siegert argues,

an abacus allows for different calculations than ten fingers; a computer, in turn, allows for different calculations than an abacus. When we speak of cultural techniques, therefore, we envisage a more or less complex actor network that comprises technological objects as well as the operative chains they are part of and that configure or constitute them. (Siegert, 58)

Having attempted to unpack the framework of cultural technique, how might this framework now be applied to an object, and how does its application influence the ways in which such an object might be interrogated? Since cultural technique overlaps actor-network theory in numerous respects, the use of the former constitutes a kind of splitting of the deceptively simple into its more complex constituent, heterogeneous components, like the splitting of white light into a spectrum by a prism. Using the prism of cultural technique, then, let us examine an odd technological construct: the Space Mirror Memorial.

The Mirror as a Stage for Remembrance

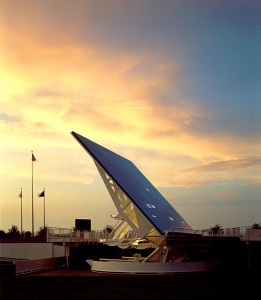

The Space Mirror memorial was constructed in 1991 by the Astronauts Memorial Foundation (AMF), a NASA affiliate. The memorial was designed by Californian architect Wes Jones, who co-founded the architectural firm of Holt Hinshaw Pfau Jones in 1987 (Jones, also an author, has written about the intersection of technology and architecture, in an interview here). The Space Mirror, a designated national memorial, is a 6ft by 6ft wall of black granite, divided into 90 square sections. On 24 of these sections, the names of astronauts killed in spaceflight related disasters have been cut, not out of, but through the granite, creating runic strings of absence in the stone. The Space Mirror was designed to track the sun in order to capture and redirect natural light through a transparent acrylic resin behind the granite wall, causing the names of the dead to glow as the light passed through the calligraphic voids cut into the granite.

The Space Mirror memorial was constructed in 1991 by the Astronauts Memorial Foundation (AMF), a NASA affiliate. The memorial was designed by Californian architect Wes Jones, who co-founded the architectural firm of Holt Hinshaw Pfau Jones in 1987 (Jones, also an author, has written about the intersection of technology and architecture, in an interview here). The Space Mirror, a designated national memorial, is a 6ft by 6ft wall of black granite, divided into 90 square sections. On 24 of these sections, the names of astronauts killed in spaceflight related disasters have been cut, not out of, but through the granite, creating runic strings of absence in the stone. The Space Mirror was designed to track the sun in order to capture and redirect natural light through a transparent acrylic resin behind the granite wall, causing the names of the dead to glow as the light passed through the calligraphic voids cut into the granite.

This highly technological dialogue with the dead raises several questions of comparison. The Space Mirror is a highly unusual memorial, relative to others we might call to mind. For example, in contrast to the Space Mirror, the sombre, static, vaguely neoclassical monuments of WWII, many of which depict groups of soldiers chiselled in valiant poses, focus more on sentimentalizing the human aspect of their deaths than on the importance of the technological shells that encased them as they fought. Although many WWII memorials may incorporate a myriad of technologies in their construction and function (the water pumps in a fountain, for example), such technologies are not explicitly presented to the viewers of these memorials as intended corollaries with the dead being memorialized. In other words, the relationship between technology and memorialization is present, but is not part of the intended memorial ‘experience’.

The wars of the 20th century were undoubtedly wars of technology (though one could easily argue this point about any war). One might examine a WWI or WWII soldier’s kit as a kind of cockpit, in which a terrified occupant was tasked with navigating the nightmarish abysses of Dieppe, of the Somme, or of Vimmy Ridge, blasted landscapes where survival depended upon the functioning of a gun, a helmet, a radio, a vest pocket, a bible, a pair of boots (to fend off trench rot), and even a wooden scaffold struggling to keep waves of mud at bay. Yet the war monuments dedicated to these dead speak little (visually or textually) about the technologies these soldiers relied upon, focusing instead on a romanticized conception of war as martyrdom, as an act of brotherly sacrifice, as a tragic clashing of nationalistic fervour with the disillusionment and horror of mechanized slaughter (it should be noted that, in his book “Shock Troops”, historian Tim Cook examines technology admirably, in terms of how it affected Canadian soldiers in WWI, from the infamous Ross rifle to the quality of articles such as coats and boots).

The wars of the 20th century were undoubtedly wars of technology (though one could easily argue this point about any war). One might examine a WWI or WWII soldier’s kit as a kind of cockpit, in which a terrified occupant was tasked with navigating the nightmarish abysses of Dieppe, of the Somme, or of Vimmy Ridge, blasted landscapes where survival depended upon the functioning of a gun, a helmet, a radio, a vest pocket, a bible, a pair of boots (to fend off trench rot), and even a wooden scaffold struggling to keep waves of mud at bay. Yet the war monuments dedicated to these dead speak little (visually or textually) about the technologies these soldiers relied upon, focusing instead on a romanticized conception of war as martyrdom, as an act of brotherly sacrifice, as a tragic clashing of nationalistic fervour with the disillusionment and horror of mechanized slaughter (it should be noted that, in his book “Shock Troops”, historian Tim Cook examines technology admirably, in terms of how it affected Canadian soldiers in WWI, from the infamous Ross rifle to the quality of articles such as coats and boots).

The Space Mirror’s tracking of the sun (originally augmented by floodlights used at night to keep the resin behind the names ablaze), required a series of complex mechanisms to keep the mirror oriented properly. This series of mechanisms proved troublesome when, in 1997, the mechanism failed. Rather than spend the money to repair the broken mirror, the AMF opted to simply keep the floodlights burning at all hours. The mirror is now lit by artificial sunlight. In lieu of the Space Race’s Cold War roots, this use of artificial sunlight during the day brings to mind English experimental writer J.G. Ballard’s response when he was asked why man had built nuclear weapons: “Because one sun is not enough”.

Commercial Scaffolding: Intersecting Networks

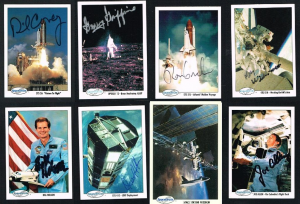

The commercial scaffolding that allowed the Space mirror to exist merits examination. The commercialization of sentiment is nothing new, but in this context, when dealing with a memorial bent on representing not only the human cost of space exploration, but the vital role technology plays as an actor in this endeavour, the roots of the Mirror take on particular significance. The 1990’s saw a resurgence of space exploration in popular culture (much like the contemporary one we are experiencing in the mid-2010’s, with the Mars rover Curiosity’s findings, the remake of the TV series Cosmos, and movies such as Interstellar and The Martian), and the AMF sought to capitalize on this trend when constructing the Space Mirror. The mirror was to be funded partly by the sale of a series of collectible trading cards depicting space exploration figures and technologies called Space Shots, and partly by the sale of Florida license plates such as the Challenger plate (Clary). Interestingly, An audit of the funding was later carried out, revealing that the agreed upon payment had not been made by Space Shots.

The commercial scaffolding that allowed the Space mirror to exist merits examination. The commercialization of sentiment is nothing new, but in this context, when dealing with a memorial bent on representing not only the human cost of space exploration, but the vital role technology plays as an actor in this endeavour, the roots of the Mirror take on particular significance. The 1990’s saw a resurgence of space exploration in popular culture (much like the contemporary one we are experiencing in the mid-2010’s, with the Mars rover Curiosity’s findings, the remake of the TV series Cosmos, and movies such as Interstellar and The Martian), and the AMF sought to capitalize on this trend when constructing the Space Mirror. The mirror was to be funded partly by the sale of a series of collectible trading cards depicting space exploration figures and technologies called Space Shots, and partly by the sale of Florida license plates such as the Challenger plate (Clary). Interestingly, An audit of the funding was later carried out, revealing that the agreed upon payment had not been made by Space Shots.

Much like memorabilia from WWII and the Cold War, these products represent a commercialization of sentiment, nostalgia, tragedy, etc., however they also represent the incorporation of technology into the realm of sentiment. Siegert urges us to ask “not ‘how did we become posthuman?’, but ‘how was the human always already historically mixed with the non-human?’” Each of these license plates depicts the pair of rocket boosters and shuttle, the quintessential technological icon of space travel. Many Space Shots trading cards depict non-human actors such as the Hubble telescope.

Part of why these disasters are so significant is because of the loss of money and technology, of these nonhuman actors (not to suggest that the human deaths in these instances were less significant). The focus on technological imagery in memorabilia such as trading cards and license plates, and the incorporation of sun-tracking technology in the Space Mirror monument, each represent an increasing awareness of the role of technology in remembering the dead, and in capitalizing on sentimentality. Initiating a massive operation like a rocket launch, where years of work by hundreds of people and billions of dollars (not to mention the mobilization of national and international interest) are spent on an action that, among other things, makes a door or distinction or ‘difference’ between the earthly and the non-earthly, between one era of human exploration and the other, only to have the operation fail catastrophically (in an equally grand spectacle, in terms of its tragic weight), demands a memorial that accounts for the symbolic connotations of the technologies or non-human actors that were lost, as well as the human actors.

Part of why these disasters are so significant is because of the loss of money and technology, of these nonhuman actors (not to suggest that the human deaths in these instances were less significant). The focus on technological imagery in memorabilia such as trading cards and license plates, and the incorporation of sun-tracking technology in the Space Mirror monument, each represent an increasing awareness of the role of technology in remembering the dead, and in capitalizing on sentimentality. Initiating a massive operation like a rocket launch, where years of work by hundreds of people and billions of dollars (not to mention the mobilization of national and international interest) are spent on an action that, among other things, makes a door or distinction or ‘difference’ between the earthly and the non-earthly, between one era of human exploration and the other, only to have the operation fail catastrophically (in an equally grand spectacle, in terms of its tragic weight), demands a memorial that accounts for the symbolic connotations of the technologies or non-human actors that were lost, as well as the human actors.

As a child, I often played with my dad’s old toys when visiting his parents in Edmonton, Alberta. Among my father’s childhood playthings was a series of plastic discs, about the size of poker chips, reminiscent of the Pogs that my classmates in elementary school gambled with and traded. Some of these plastic discs depicted military hardware from WWII: a jeep, a rifle, a bomber aircraft. My father also played with a 007 spy kit, a suitcase into which a toy gun could be placed, its barrel aligned with a hole in the suitcase. Plastic bullets could be covertly fired by squeezing a hidden trigger in the handle of the suitcase, which in turn pulled the trigger of the toy gun.

Such artefacts capitalize on the indirect or implicit education of children via facsimiles of technologies, but not as significantly or explicitly on the sentiment of remembrance of the wartime dead. This latter realm is generally characterized by sacredness, which has come to necessitate, increasingly, denial of the relationship between sentiment, technology, memorialization, and capitalism. If one were to investigate, I have no doubt that a wealth of material representing the intersection of the aforementioned spheres could be dredged up from much earlier decades to illustrate the historical presence of such networks.

Works Cited*

Berhard, Siegert. “Cultural Techniques: Or the End of the Intellectual Postwar Era in German Media Theory.” Theory, Culture and Society. 30.6 (2013): 48-65. Sage Publishing. Web. 5 Oct 2015.

Clary, Mike. “American Album: As the Space Mirror turns, focus is on funds: Amid structural problems at the Astronauts Memorial, a probe of its financing is launched.” Los Angeles Times. August 19, 1991. Web. 14 Oct 2015. http://articles.latimes.com/1991-08-19/news/mn-633_1_space-mirror

Kramer, Sybille and Horst Bredekamp. “Culture, Technology, Cultural Techniques- Moving Beyond Text.” Theory, Culture and Society. 30.6 (2013): 20-29. Sage Publishing. Web. 6 Oct 2015.

Sterne, Jonathan. “Bordieu, Technique and Technology.” Cultural Studies. 17.3/4 (2003): 367-389. Routledge Taylor and Francis Group. Web. 5 Oct 2015.

*All images are sourced from Google Image searches

Further Reading