The post Government Info-Tech Research Officer “Track[s] Emotions in Novels and Fairy Tales” appeared first on &.

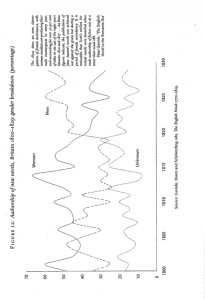

]]>“Empirical assessment of emotions in literary texts has sometimes relied on human annotation” but now an algorithmic “system determines which of the words exist in our emotion lexicon and calculates ratios such as the number of words associated with an emotion to the total number of emotion words in the text” for novels, Shakespeare, and Brothers Grimm fairy tales (pp. 2, 3). There are no references to Franco Moretti, literary criticism and critical theory, or precedents in fairy-tale analysis such as the ATU Index. Google’s n-gram corpus data and visualization software, which allows you to “Search lots of books” (as opposed to a specific number? are we simply drawing lots? from the “mind of God,” as a Google co-founder once famously called Google), is the Script/ure used (examples of Google data visualizations here).

NRC author Saif Mohammed sees a bright future for the technology in affect surveillance: “Ultimately, he thinks emotion-based software may help us better keep tabs on depression or online harassment and bullying, track emotions on Twitter to forecast riots and better deploy resources, or measure sentiment towards government policies and controversial issues.”

The post Government Info-Tech Research Officer “Track[s] Emotions in Novels and Fairy Tales” appeared first on &.

]]>The post Boot camp: Discourse That Graphs its Discourse: “Fuck”-Clustering appeared first on &.

]]>Limp Bizkit’s “Hot Dog,” from Chocolate Starfish and the Hot Dog Flavored Water (2000), engages the same kind of satiric magnification as the supercut: a dense clustering of a discursive particle, in this case “fuck”. Andrew Piper calls this the defining character of discourse: “the cluster or concentration – Verdichtung…, a thickening of language” (384). However, the example of a content in which this character of discourse is exploited to an extreme illustrates the porousness between “content” and discursive analysis itself – especially when, in the case of “Hot Dog”, singer Fred Durst’s voice has occasion to boast a self-analysis: “If I say ‘fuck’ / two more times / that’s forty-six ‘fucks’ in this fucked-up rhyme” (2:05).

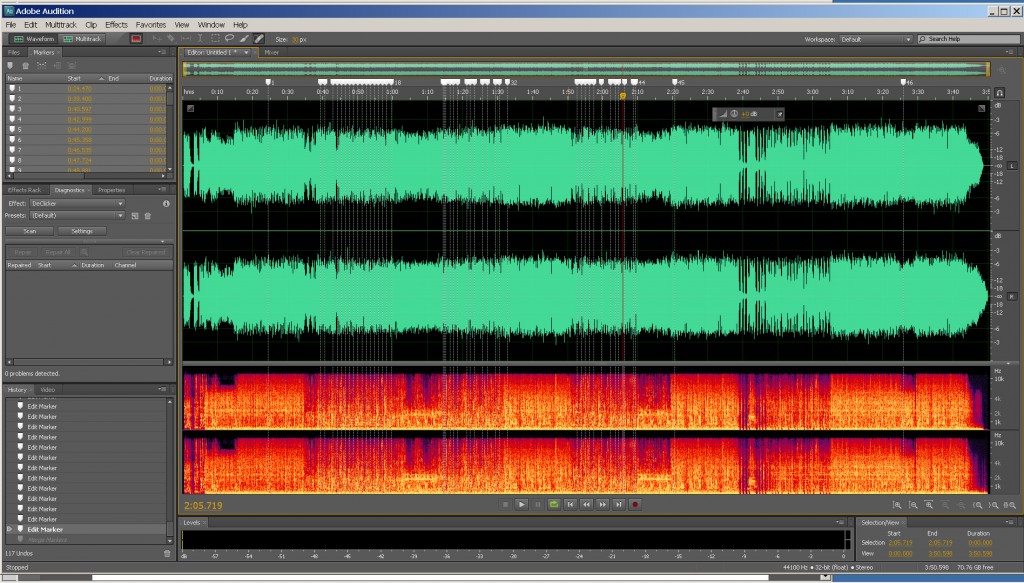

To analyze the self-analysand’s “analysong,” I played an mp3 version in the audio-editing program Adobe Audition, and placed a marker at each “fuck” (Fig. 1). This produced forty-six markers, meaning Durst’s count is numerically correct, but also revealing some parameters determining this number, and why such a numerical analysis as Durst’s may not function in the way we expect.

First, “fuck” defines not “just a word” (as the song calls it at 1:15) but the morpheme as it appears in a paradigm of affixed forms (plural –s, past-tense –ed). So, while we hear Durst say the word “fuck”, what we may think of as a “word” is not, grammatically, without an inaudible variable: “fuck*”.

Second, Durst’s count is non-recursive. “If I say ‘fuck’ / two more times, / that’s forty-six ‘fucks’ in this fucked-up rhyme” seems like a proposition whose “then” fulfills the two “fucks” conditioned by its “if” – but only until one hard-counts the instances to arrive at forty-six.

Third, similarly, Durst’s count assumes defined edges for the song that concretize it as such. Had the line been something like, “If you listen to this song, plus George Carlin’s ‘Seven Words You Can Never Say on the Radio’ / point-five more times / that’s at least 46 fucks that will have played in your proximate aural vicinity,” it would be non-self-enclosing.

But these revealed parameters only underline just how unimportant the exact count is. Isn’t it good enough to say that “46” in this context simply means “a lot”? “There’s a lot of F-bombs in this song,” is all the song’s 46n “fuck*” (where n is the number of listens) are already saying. The song’s explicit self-count only emphasizes what’s already formally evident by the cluster-driven hyperbole, a device whose efficacy revolves around producing degrees of recursively qualifiable emphasis rather than of quantifiable exactitude. Durst’s providing a number (the exactitude in this case is precisely what’s ridiculous) is just another multiplier in a series in which each element hyperbolizes the value of every other. All “fucks” are more than their sum when forty-six cluster in close proximity.

This much is to acknowledge the importance of frequency (“ratio” [Piper 379]) over simple number-value: Durst’s count means nothing without the immediate context of the song. But even here, saying that there are 46 “fucks” per 436 words (i.e. about one “fuck” for every ten words), or that there are almost two “fucks” for every second of song, still only says that there are “a whole lotta ‘fucks’.” The actually crucial assumed ratio, rather, is one that defines the cluster as emphasis at all. Emphatic/hyperbolic relative to what (beyond the song)? The key assumption – the key intuitive reading-at-a-distance – is what the song leaves implicit, its content an index to: that there is a lot of polite discourse in which “fuck” cannot be said (the implied specific target being mainstream radio airplay). In which case, if we can recognize this much on hearing, will the audiograph not do as well for us as its graphic image? And what of the fact that, by setting itself up as a cluster, “Hot Dog” makes itself attractive to cluster analysis, and sets itself up for a successful one?

Works Cited

Piper, Andrew. “Reading’s Refrain: From Bibliography to Topology.” English Literary History 80 (2013): 373-399. Web.

The post Boot camp: Discourse That Graphs its Discourse: “Fuck”-Clustering appeared first on &.

]]>The post Probe: Phonographs, Maps, Carpentrees appeared first on &.

]]>On what scale is Chang’s a scalar reading project? How does a noisy audio palimpsest multiplying “one” object compare with the pristine genre-spanning graphs of Moretti or the intricate Göethe-corpus topologies cited by Andrew Piper?

It’s tempting to dismiss Chang’s White Album remix as simply the synchronic equivalent of a less sophisticated “vernacular” of distant-reading like the supercut. But Ian Bogost’s proposal that object-oriented ontologists need to graduate from the logocentrism of writings which do ontology in theory, to the carpentry of crafted objects that put ontologies into practice (e.g. 91-2), suggests that graphing-objects similarly needn’t be constrained to the logo-visual. Can the “palimpsest” component of Chang’s clearly praxis-oriented project be considered, then, as “auditorizing” data in the same way that one of Moretti’s graphs visualizes data? A pertinent question, given “today’s growing interest in the field of information visualization” (Piper 388).

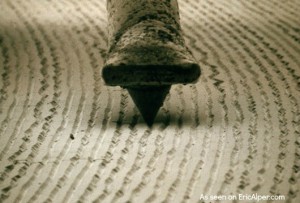

After all, what is graphic representation? “Graphing,” as the etymology suggests, is a form of writing, which is a form of drawing. As Piper points out, “Friedrich Kittler’s argument, of the two-thousand-year-old antipathy between the alphabetic and the numerical[,]” is a “false notion” (380). Nonetheless, the invisible Cartesian latticework gridding any typeset page, into whose discursive position of “prose” most writing gets indifferently wrapped, has continuously disarticulated graphemic writing from the genre of alphanumeric graphical representation. Notably the same, however, cannot be said for music. From its earliest forms, well before Descartes and de Fermat, the musical staff makes little secret about its dimensionality: pitch vs. time. But: “non-musical” texts encode sound no less! They, too, graph sounds against time, within a limited repertoire of graphemes (e.g. 26 letters vs. 12 tonic pitches). Thus, while literary analysis may have preoccupied itself with “the two-dimensionality of the page or the three-dimensionality of the book” (Piper 383), its broader problem has been that it would not even have articulated its conceptions of the page and book as such, for only recently has it begun to consider its objects in dimensional terms whatsoever. Meanwhile, graphing (alphabetic writing) and graphing (alpha-numeric charting) and graphing (musical scoring) have remained distinct. And a musical graph is expected to be performed aloud, with the body, whereas a philosophical or statistical graph is expected to be performed in silence, with the head. Cartesian plane indeed.

Sound, in short – by which I don’t mean speech – has been systemically excluded as a medium for philosophy, let alone for demonstrative data representations, and this has everything to do with philosophy’s logocentric tradition in emphasizing content over form, music being strongly articulated to the latter. But if we re-articulate the above various forms of writing as graphings more broadly, can we then likewise re-articulate any performance of a graphing as itself a form of graphing, even if this performance is sensually other to the visual (as the iconized data of Piper and Moretti, despite their iconoclasm in other respects, tends to emphasize)?

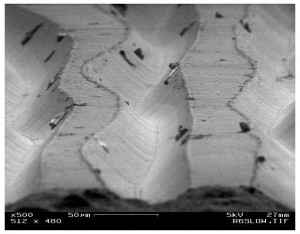

Things become clearer if we elaborate further on what graphing (i.e. writing) is, and illustrate with vinyl. In Vilém Flusser’s description, “writing…was originally an act of engraving. The Greek verb ‘graphein’ still connotes this…. [T]o write is not to form, but to in-form, and a text is not a formation, but an in-formation” (Roth 26). It is such information that we find grooving a vinyl record: a form of information whose curves, unlike these graphemes that I type, is more readily articulable to the curves of information that discourse has arbitrarily distinguished as graphing (see Figs. 1 & 2). Indeed, confusions have arisen at all because we speak of information in such logocentric terms as Flusser himself does, whereas information theorists speak of it in terms of waves, frequencies – something that writers like Piper do evoke with statements like, “any textual field is at base a configuration of differential repetitions” (394). Whereas, now that we’ve re-articulated graphing as information, we can see how the curves of Figure 2 could just as easily be transfigured into audio as could the curves on the vinyl. It would be up to us listeners to re-articulate our logo-visual biases to interpret the “audiograph” as well as we can its visualized score. But is it just our lack of familiarity with interpreting an “audiograph” as a graph that would other it as comparably “messy” (in John Law’s term), or can such graphs simply not compare with pristine Cartesian visuals, say for reasons of transfiguration?

The approach to this question is rolled up in what the convergence of Figures 1 and 2 illustrates: the zero-point at which “distant” and “close” break down into “a continuous spectrum of focalization” (Piper 382). This is a useful place to begin discussing Chang, whose “1 x 100” audiograph intuitively seems more of a “distant reading” than the audiograph from a single record. But, having dismissed the distant-close binary in favour of an ontology of surface relations, we shall see that “more” no longer necessarily means more, nor “less” less. If all graphs record regularities of information, then the question becomes not about perspectival proximity, nor even exactitude, but about how and what each object – 1 White Album vs. 100 White Albums simultaneously – graphs differently. What do the regularities of one single White Album measure in comparison with the overlayed regularities of one hundred White Albums?

Close-distant reading: We needn’t hear 100 versions at once for us to know that our single copy is not singular, that the “object” we listen to is much larger than its packaging’s pretense to unity; indeed, the fact that it is not one-of-a-kind is likely how and why we and the object found each other in the first place. For Foucault, the very fact that we have a White Album playing at all means that it is discursively sanctioned, corresponding to a discursive statement, a regularity within a field of discourse: the grooves of a single White Album already graph a regularity concerning White Albums. Like the statement “QWERTY,” produced by a standard keyboard, any printing of a White Album is a statement produced by a similarly standardized mass-printing device programmed to print the White Album from a “master” copy or image, such that any single vinyl record graphs a regularity of discourse, a record of the process of inscribing White Albums with the grooves that constitute White Album-ness. A White Album graphs, more accurately than its hundred-fold multiplication, the pristine Gaussian “mean” of White Album articulation. Mass production’s claim to mass identity is its mass delusion, but an individual album is nonetheless a graphical index of its mass-media ur-stamp. Indeed, this is so because it is such standardization’s goal: to distribute the closest approximation of the Same, so that a claim for Sameness may be made, a common-place created.

Distant-close reading: What do the 100 albums played at once tell us, then? We needn’t listen to know that there will be much “noise”; indeed, judging by the present recording, if Chang carries through with his plan to mash up his 600+ records, we would hear nothing but noise. What, then, does this audio-topography do? Ostensibly it graphs the relative fluctuations between 100 versions – but not in any distinct way. Can we distinguish all the tracks (and their interrelations) as we might in a visual representation? Indeed, there is “noise” because there is information lost – each element in the audiograph interferes with every other. Or is the noise we perceive as much a function of our bias to the logo-visual? If for topology “the ‘object’ is merely the identification of a visual thickness” (Piper 384), then Chang’s project fits the description, but does this hold if topology considers “reading” only as “a deeply visual experience” (Piper 387, emphasis added)? Alternatively: Friedrich Kittler engages in an alien phenomenology of the phonograph to describe its recordings as constituting the real: “The phonograph does not hear as do ears that have been trained immediately to filter voices, words, and sounds of noise; it registers acoustic events as such. Articulateness becomes a second-order exception in a spectrum of noise” (Kittler 23). Such engagement raises the question: Is (topo)graphing unable to deal with acoustic events as such? Would the noise be better approached from the phenomenology of an alien object?

Works Cited

Bogost, Ian. “Carpentry.” Alien Phenomenology, or, What It’s Like to Be a Thing. Posthumanities. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012. 85–111. Print.

Roth, Nancy A. “A Note on ‘The Gesture of Writing’ by Vilem Flusser and The Gesture of Writing.” New Writing: The International Journal for the Practice and Theory of Creative Writing 9:1 (2012): 24-41. Web.

Kittler, Friedrich A. Gramophone, Film, Typewriter. Trans. Geoffrey Winthrop-Young and Michael Wutz. Stanford UP: Stanford, 1999. Print.

Law, John. “Making a Mess with Method.” Lancaster: The Centre for Science Studies, Lancaster University, 2003.

http://www.comp.lancs.ac.uk/sociology/papers/Law-Making-a-Mess-with-Method.pdf

Moretti, Franco. “GRAPHS, MAPS, TREES: Abstract Models for Literary History – 1″. New Left Review 24 (Nov-Dec 2003): 67-93. Web.

Paz, Eilon. “Rutherford Chang – We Buy White Albums.” Dust and Grooves: Vinyl Music Culture. 15 Feb 2013. Accessed 10 Oct. 2013. http://www.dustandgrooves.com/rutherford-chang-we-buy-white-albums/

Piper, Andrew. “Reading’s Refrain: From Bibliography to Topology.” English Literary History 80 (2013): 373-399. Web.

The post Probe: Phonographs, Maps, Carpentrees appeared first on &.

]]>The post Show Facts, Hide Facts: Applying Latour to Database Structures appeared first on &.

]]>In view of our reading of Latour’s rearticulation of the assumptions informing the concepts of “facts” and “values” into new terms that recognize the processual cyclicity of institutionalizing always-debatable uncertainties into useful certainties, and in view of Alice Munro’s having just been awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, an article entitled “Denied Nobel Prize Yet Again, Margaret Atwood Plots Post-Apocalyptic Revenge” seems timely. The article appears on the website Newslo, which boasts (with apropos unabashedness with respect to facticity) the title of “The First Ever Hybrid New/Satire Platform!” The title captures accurately, however, the Newslo site’s hallmark article-viewing functionality: a toggle for “Show Facts” and “Hide Facts” foots every article. Activating the former button highlights the portion of the article that has been institutionalized to the realm of what we would previously have called facticity; re-negating these highlights (back to the article’s default appearance) returns smoothly and non-libelously the factual portions into formal homogeneity with the sensationalist satirical tabloid remainder. “Just Enough News,” runs the site’s motto, which is just as well an ironic motto for news in general nowadays: there’s too much news, and yet never enough “(f)actual” news in that news (and never enough fiction in our “fiction“). How can we better define that “just enough” (with pun on “just”)? We need what Latour proposes: a better “power to take into account” (Facebook account or otherwise): we need to evolve our filter-feeders.

Indeed, Newslo’s filtering system typifies the related problem of facticity in regard to digital public spheres that we discussed both yesterday in relation to a Quebec provincial voting commercial, which we argued exemplified the complex relations governing the way in which the mob rule of social media gets billed as democracy via that social media itself, as well as last month in relation to our discussion of print newspapers versus databased newspapers and the personalized newsfeed. “Filter bubbles,” Ted Talker Eli Pariser calls it, this Internet censorship phenomenon in which our bias towards our own politics of interest can actually work against our own interests – especially when, as Pariser relates, Facebook one day decides to run an algorithm (just for “you,” i.e. for you) that converts all your visible news into whatever your Good News happens to be. While the talk is scarcely worth skimming beyond what I am graciously filtering for you, Pariser does end up proposing that databases like Google adopt what amounts to an extension of the logic of Newslo’s system: namely, including among our “sort by” options checkboxes for things like “Relevant”, “Important”, “Uncomfortable”, “Challenging”, and “Other Points of View”. The metaphysics of presence points to an obvious problem with this system, or rather with the utopian version of it (a database will never represent what is truly Other to it – we, and even Google, simply cannot know how “Other Points of View” is itself being filtered; and is a comfortable way to find the “uncomfortable” possible?), but nevertheless the gesture seems valuable, and maybe even represents a crude attempt at doing for the database what John Law proposes scholars do for research in general: making explicit to our readers the always-messy contingency of that research. Perhaps databases should have a “messy” filter (kind of like the trope of the button which you’re told never to press because no one knows what it does), which when you press it simply puts everything through a glitch-randomizer and fucks everything up.

It is such mess, though, that Latour likewise encourages as the one of two requirements of his proposed initial phase for institutionalization (what in the old language we would call fact-making), the phase of taking into account all of the entities that we have at our disposal to debate for institutionalization candidacy: namely, the requirement of perplexity, a “provocation (in the etymological sense of ‘production of voices’)” in which “the number of candidate entities must not be arbitrarily reduced in the interests of facility or convenience” (110). Its corollary is the requirement of relevance – considering the relevance of the various stakeholding voices to perplex what is being, by debate, perplexed. This latter somewhat relates to Pariser’s proposed (re)search filter category, but more to that mark is the requirement of hierarchization in Latour’s second of the two institutionalization phases, arranging in rank order. For, Pariser’s category of “Relevance” (and rather than simply pertaining to the already-familiar category of “sort by relevance” vis-a-vis search terms) comes in critical response to Mark Zuckerburg’s cited remark that “[a] squirrel dying in front of your house may be more relevant to your interests right now than people dying in Africa.” Pariser’s point is that, if newsfeeds or other search results are ever to even approach something more like the impossible ideal of information democracy to which popular media discourse so often articulates them, then the squirrel pictures that come up in our newsfeeds should perhaps not be placed at the same level of relevance as humanitarian crises in what Latour calls society’s “hierarchy of values” (107) (which also, notably, functions by a “[r]equirement of publicity” [111, emphasis added]).

The comparison to be made, then, is between the (in the old terms) “fact-evaluation” process that Latour proposes for constitutional democratic government, and the way in which information is similarly filtered to and filterable by the public of such democracies within their digital news and (re)search platforms. Latour’s proposed process begins with perplexity and relevance – in other words, the collection of search results (the terms – relevance – and their results – initially, perplexity) that then, in the second part of the process, the move toward actual instutionalization (“closure”), must get hierarchized accordingly in terms of their hierarchical ethical valuation. In sum, it would seem that, in extension to Newslo’s and Pariser’s unique filtration systems, and indeed as a corollary component to the type of public network resultant of precisely the kind of (public sector) debate apparatus that Latour proposes, our new digital filtration systems should involve not just parameters like “Show Facts” and “Relevant” but precisely such a process as Latour’s, with its unique re-articulation of “facts” and “values” into less contradictory categories. Then a system such as Newslo’s could only constitute absurdity insofar as “facts” would no longer be a category for filtration. But more importantly, because the relative contingencies of what we used to call “facts” (and get mixed up with “values”), and the (traces of the) process by which they became such, might be explicitly built into all our articles and newsfeeds and other search databases. That is, the equivalent of “Show facts”, for example, would show (by a kind of markup, perhaps) what had been successfully put through Latour’s process of institutionalization.

Otherwise, Margaret Atwood might still be in the running, according to her own personalized fantasy newsfeed. For the division between “facts” and “values” (where the latter equals the explicitly skewed satire in Newslo’s articles) is never so clear as Newslo makes it. Hence the need and use for Latour’s proposed new articulations.

Works Cited

Latour, Bruno. “A New Separation of Powers.” Politics of Nature: How to bring the Sciences into Democracy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2004. 91-127. Print

Law, John. “Making a Mess with Method.” Lancaster: The Centre for Science Studies, Lancaster University, 2003.

http://www.comp.lancs.ac.uk/sociology/papers/Law-Making-a-Mess-with-Method.pdf

The post Show Facts, Hide Facts: Applying Latour to Database Structures appeared first on &.

]]>