Boot camp: Discourse That Graphs its Discourse: “Fuck”-Clustering

To accompany our discussions of reading’s scalability and graphing’s authority more broadly, consider an example of an object that includes in its own content a corpus-analysis – of itself.

Limp Bizkit’s “Hot Dog,” from Chocolate Starfish and the Hot Dog Flavored Water (2000), engages the same kind of satiric magnification as the supercut: a dense clustering of a discursive particle, in this case “fuck”. Andrew Piper calls this the defining character of discourse: “the cluster or concentration – Verdichtung…, a thickening of language” (384). However, the example of a content in which this character of discourse is exploited to an extreme illustrates the porousness between “content” and discursive analysis itself – especially when, in the case of “Hot Dog”, singer Fred Durst’s voice has occasion to boast a self-analysis: “If I say ‘fuck’ / two more times / that’s forty-six ‘fucks’ in this fucked-up rhyme” (2:05).

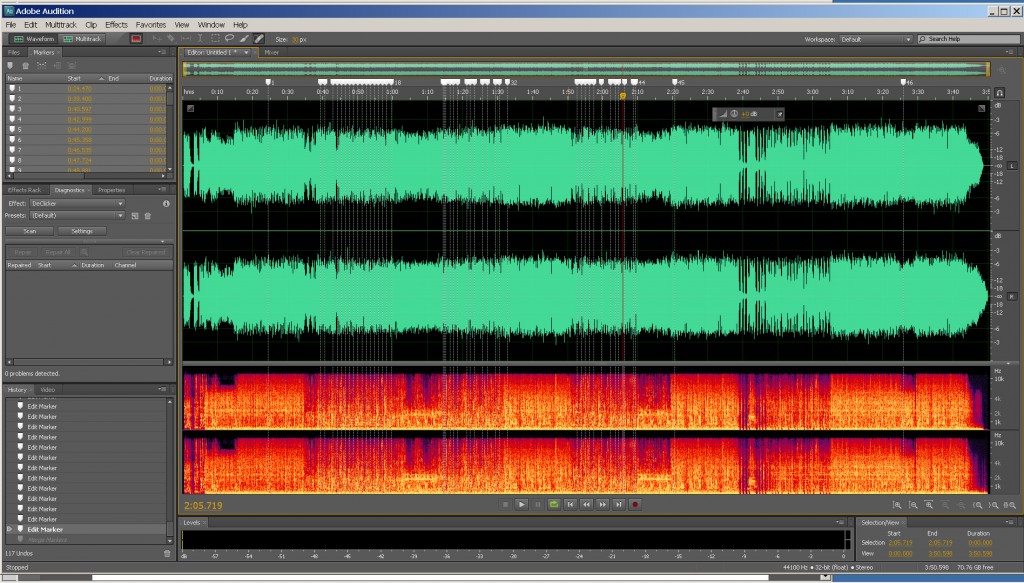

To analyze the self-analysand’s “analysong,” I played an mp3 version in the audio-editing program Adobe Audition, and placed a marker at each “fuck” (Fig. 1). This produced forty-six markers, meaning Durst’s count is numerically correct, but also revealing some parameters determining this number, and why such a numerical analysis as Durst’s may not function in the way we expect.

First, “fuck” defines not “just a word” (as the song calls it at 1:15) but the morpheme as it appears in a paradigm of affixed forms (plural –s, past-tense –ed). So, while we hear Durst say the word “fuck”, what we may think of as a “word” is not, grammatically, without an inaudible variable: “fuck*”.

Second, Durst’s count is non-recursive. “If I say ‘fuck’ / two more times, / that’s forty-six ‘fucks’ in this fucked-up rhyme” seems like a proposition whose “then” fulfills the two “fucks” conditioned by its “if” – but only until one hard-counts the instances to arrive at forty-six.

Third, similarly, Durst’s count assumes defined edges for the song that concretize it as such. Had the line been something like, “If you listen to this song, plus George Carlin’s ‘Seven Words You Can Never Say on the Radio’ / point-five more times / that’s at least 46 fucks that will have played in your proximate aural vicinity,” it would be non-self-enclosing.

But these revealed parameters only underline just how unimportant the exact count is. Isn’t it good enough to say that “46” in this context simply means “a lot”? “There’s a lot of F-bombs in this song,” is all the song’s 46n “fuck*” (where n is the number of listens) are already saying. The song’s explicit self-count only emphasizes what’s already formally evident by the cluster-driven hyperbole, a device whose efficacy revolves around producing degrees of recursively qualifiable emphasis rather than of quantifiable exactitude. Durst’s providing a number (the exactitude in this case is precisely what’s ridiculous) is just another multiplier in a series in which each element hyperbolizes the value of every other. All “fucks” are more than their sum when forty-six cluster in close proximity.

This much is to acknowledge the importance of frequency (“ratio” [Piper 379]) over simple number-value: Durst’s count means nothing without the immediate context of the song. But even here, saying that there are 46 “fucks” per 436 words (i.e. about one “fuck” for every ten words), or that there are almost two “fucks” for every second of song, still only says that there are “a whole lotta ‘fucks’.” The actually crucial assumed ratio, rather, is one that defines the cluster as emphasis at all. Emphatic/hyperbolic relative to what (beyond the song)? The key assumption – the key intuitive reading-at-a-distance – is what the song leaves implicit, its content an index to: that there is a lot of polite discourse in which “fuck” cannot be said (the implied specific target being mainstream radio airplay). In which case, if we can recognize this much on hearing, will the audiograph not do as well for us as its graphic image? And what of the fact that, by setting itself up as a cluster, “Hot Dog” makes itself attractive to cluster analysis, and sets itself up for a successful one?

Works Cited

Piper, Andrew. “Reading’s Refrain: From Bibliography to Topology.” English Literary History 80 (2013): 373-399. Web.