Performance, video formats, and digital publication in a Latin American context

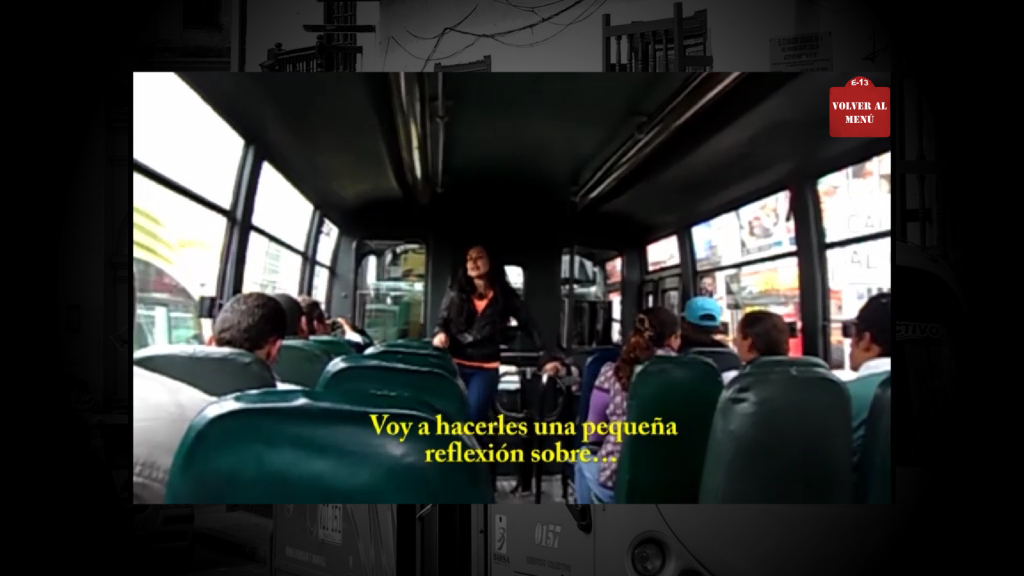

Flaubert: 20 rutas consists of a series of performances made by Alejandra Jiménez in Colombia, where she delivered speeches based on texts by Gustave Flaubert to random users of the Bogotan public transport system. It is an intervention in the sense that it gets to an audience without it knowing or even wanting to experience such performance, rather than the audience consciously attending an artistic event. Also, if only haphazardly, it records the reactions of the public—sometimes they clapped at the end of the speech, sometimes they would remain silent, one lady would give her some flyers and information about God. Jiménez’s reflections on her performative interventions in her MFA dissertation (also called Flaubert: 20 rutas) seek to question the implications of transit and mobility in Colombia’s capital, as well as the replacement of old buses and busetas (small buses) by more modern models, the ways in which drivers used to appropriate their units and the advent of non-place-like environments in the new buses—cold, gray, almost antiseptic (Augé 2000; Jiménez 2013).

So Flaubert: 20 rutas is actually two works or, as I usually call them in this probe, two artistic products: the first one is a series of performances recorded in low-fi video—which is not just a byproduct of the performances but, as we will see, will take them to another sort of materiality. The second one is the research-creation dissertation defended by Jiménez at Universidad Nacional de Colombia (UNC). Given that the latter was already made public by the UNC web portal, the interest in the “publication” of Flaubert: 20 rutas was focused in the videos, since it recorded the reactions of the audiences randomly “formed” by Jiménez’s interventions on Bogotá’s buses and busetas, and therefore constituted a sort of “invitation to reflection” without recurring to academic rhetoric.

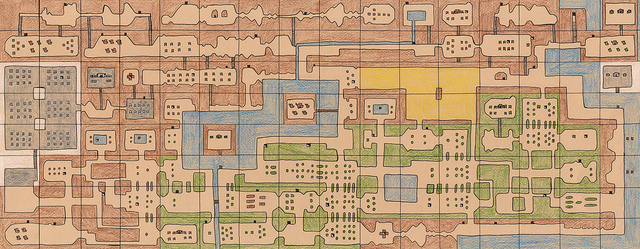

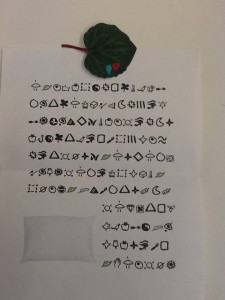

The videos, merged in F4V format, were gathered and displayed in a custom-made Adobe Flash Player application interface, made under Jiménez’s commission. Given that the only non-textual traces of the performance available for “publication” were the F4V files, the interface gave them a “database aspect”. All of the 20 performances are listed together in a 5 x 4 slot interface. Each slot is randomly numerated and identified with a distinctive title or topic: “Alcohol,” “History,” “Artists,” “Turning 30,” and so on. Recording the performances makes the project ambiguous in terms of function and materiality. As in the case of PDF, which reproduces paper in a digital environment (Gitelman 2011, 115), F4V is a digital file that mediates a video recording device, which in this case mediates in turn a time-bound artistic performance. It is the recording of the recording of the performance. But whereas a rose stops looking like a rose after several photocopies, in the videos the loss is both visual and aural, since not all the background details are clear or audible.

Before discussing video file formats as cultural artifacts in Latin America it would be good to give an overview of their proliferation and the process of standardization set forth by the ISO base media file format. Just as in the case of MP3 (Sterne 2006, 826), video files are called container or wrapper file formats, a sort of metafile which may be capable of storing multimedia data along with metadata for identification, classification, and reproduction purposes. Some container formats can be reproduced across different platforms. When I started downloading videos to play them on a computer, the most common file format for PCs was Microsoft’s AVI (Audio Video Interleaved), whereas Apple used QTFF (Quick Time File Format). Macromedia’s FLV (Flash Video) first appeared some years after AVI, and the interesting thing about FLV is that it supports streaming, making it easy to share, play and store in online digital environments, while it has a relatively small size, perfect for low-bandwidth internet technology. It became widely used by video streaming websites like YouTube and Reuters, but even before that Flash Player—Macromedia’s also small viewer application—was already popular after being integrated as a free plugin to the then famous Netscape internet browser. When Adobe bought Macromedia, in 2005, Flash Player was the most used multimedia player worldwide, either as an installed application or as a browser plugin, surpassing Quicktime, Java, RealPlayer, and Microsoft Media.

Despite FLV’s hype, when the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) came up with its base media file format, Quicktime’s QTFF was chosen as the base for standardization, probably because its potential components (audio, video, text for captioning, and metadata) were slotted in different “sub-containers”, which allows for edition and revision of specific parts without having to re-write all the information every time something is modified. From that moment, the authors of FLV have strongly encouraged users to switch to new container formats aligned with the ISO base media file format standards, such as MP4 for audio and F4V for multimedia.

Following the generalized call for standardization, the multimedia files for Flaubert: 20 rutas are encoded in F4V format. However, its quality makes it difficult to be uploaded to high-definition video websites supporting F4V, such as Vimeo, and it is more akin to low-fi environments like a great part of YouTube’s content. Although these videos are the registration of the core material for her research-creation project, the only published product so far has been the thesis dissertation. The videos allow for the ephemerality of the performance to be recontextualized in a digital environment, “micromaterialized” as proposed for the MP3 (Sterne 2006, 831-832) and therefore given a physical existence, however minute and encrypted it is. As in the initial functions given to gramophones (“storing”, so to say, the voices of people before they die), in Flaubert: 20 rutas the recording and digitizing of the performances made by Jiménez in the Bogotan public transportation system is a prime example of how to promote critical thinking out of creative events, while at the same time trying to overcome the temporal restrictions embedded in artistic practices such as music, sound art, and performance.

This probe will now raise some questions about the “publication” of the videos and its accompanying Flash Wave interface in a Latin American context. By “publication” I mean the public release of cultural artifacts through a mediation system, such as a publishing house. The work of mediation agents, such as editors and curators, has been widely analyzed by authors like Pierre Bourdieu as being fundamental for the acknowledgement of value and importance of cultural objects within capitalistic societies. Bourdieu asks who “authorizes the author” (2010, 156) in order to address how mediation agents (known in media studies as “gatekeepers”, see Shuker 2005, 117) deny the economic value of the cultural objects they promote and in so doing they “bet” for their potential symbolic value for a determined audience in a given artistic field. Without such “bets”, external and peripheral to their creative work, artists are arguably less visible in the artistic fields (Bourdieu, 2010).

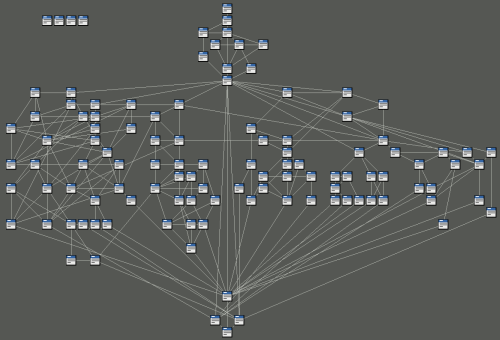

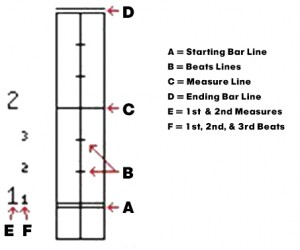

Now, this is one way of seeing it. Clearly, publishing houses and galleries are nothing without artistic products. It is the commodity they commercialize. But the articulation of independent publishing collectives has the capacity to disrupt these hierarchical types of mediation. In the case of Flaubert: 20 rutas, the initial interface for the videos (see image below) was made by a Colombian programmer, whereas some arrangements have to be done by the programmer who will upload and maintain the site (designated by the publishing collective). Extra menus will be added in each “route” to increase the navigability experience and include complementary material—either transcriptions, critical reflections, or other related creative texts. A “shuffle” or random playing function, conceived by the first programmer but not given a visual interface, will be finally installed.

As I have suggested, one of the most interesting aspects these videos show is the difficulty to realize a performative intervention such as the one proposed by Jiménez. Randomness, which is at the very core of the creative process through the choosing of a determinate bus/audience, is reproduced or enacted several times throughout the project (the non-sequential numbering of the clusters, the “shuffle” function, and so on). In that sense, the idea of distributing Flaubert: 20 rutas for an ideally greater audience through the creation of a website interface seems to be in contradiction with the ephemerality that permeates the idea of this performance—and of performativity in general.

My concerns about the publication of this project in a Latin American context have to do mainly with functionality and accessibility. In Mexico, Colombia, and presumably in the rest of Latin America it is not common to have Flash Player installed as an application, but rather as an internet browser’s plugin. This means, on the one hand, that FLV is generally used only when accessed through streaming via YouTube or similar websites, and on the other that platform-specific formats like AVI are preferred when storing videos in a hard drive. Jiménez had the initial project of supplementing a CD with the digitized version of the videos with a FlashWave interface, which nevertheless restricted its playability to PC and impeded to play it as a DVD or VideoCD format. To understand why discussing format presentation is so important in a Latin American context, it is important to note that neither video disc players nor personal computers are commodities shared by all of the Latin American populations.

How different is the gatekeeper’s work from that of an artist uploading her/his videos on YouTube and somehow building a visualization interface for them, perhaps using predetermined template websites like Wix? The bourgeois bohemian sacralization of the artist as dedicated solely to the creative process, without being involved in the “dirty job” of getting an audience for it (Bourdieu 2010, 158), is highly responsible for the importance of mediation agents in the artistic fields. But rather than seeing mediation systems as opportunistic niches for the commodification of artistic objects, independent publishing collectives propose collaboration as a means to de-articulate the power hierarchies inherent in the work of mediation (here I’m using “work” in the same way Stuart Halls uses it in The work of interpretation, that is, as an effect exercised and set into action by mediation–the work mediation that “makes” upon its components). In that sense, most of the designing part was already done when it got to the hands of the independent publishing collective. The work of the next designer is for adaptability to the internet and “maintenance”, so to say. As they say in the editorial profession, “Everything is perfectible.” This does not mean the collective had inverted (either in economical or symbolic ways) so much as it could have if the author had not commissioned the creation of the digital interface beforehand. But it is exactly this focus on the mechanism of collaboration that can rather potentially offer a wider audience for a work that was buried under academic and temporal barriers. Of course, that does not prevent the publishing collective from adding its logo on the displaying menu, as there is in the end a collective “inversion” in the artistic product. Are the underlying structures of mediation questioned through this type of collaborative project? I do not totally think so, but I consider that it poses a working methodology open to the possibility of such questionings. What are publishing houses, then? Hubs full of nodes or links. Networks connecting to other networks connecting to other networks.

However, it is important to remember that in Latin America (and also in any other place touched by globalization), access to mediation systems is transversally restricted in terms of class/income, race, and gender. Any decision to use a technological device to transmit artistic media is therefore biased from its very conception. The practical objective becomes more fundamental than the ethical one: the technology with the biggest audience potential wins, and that is of course internet. Discs are in the process of becoming fully obsolete, just as 8-track cartridges, cassettes, and laser discs. But internet does not assure a durability of the database. The underside of internet is its potential for ephemerality. The hosting site can expire and not be renewed, and the database would be lost, if it is not lucky enough to be recorded by a database like the Internet Archive. So the “triumph over ephemerality” is probably delusional, while the supposed release of an artistic object to a wide audience is biased in transversally oriented levels.

References

Augé, M. (2000). Los no lugares. Una antropología de la sobremodernidad. Barcelona: Gedisa.

Bourdieu, P. (2010). El sentido social del gusto. Elementos para una sociología de la cultura. Buenos Aires: Siglo XXI Editores.

Gitelman, L. (2014). “Near print and beyond paper: knowing by *.PDF.” Paper Knowledge: Toward A Media History of Documents. Durham/London: Duke University Press, 111-135.

Jiménez, A. (2013). Flaubert: 20 rutas. Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia. MFA Thesis.

Shuker, R. (2005). Popular Music. The Key Concepts. London/New York: Routledge.

Sterne, J. (2006). “The mp3 as cultural artifact.” New Media & Society, 8 (5), 825-842.